ABSTRACT

Protein intake has been identified as a key modifiable factor in preventing and managing sarcopenia, a common age-related condition characterized by the loss of muscle mass, strength, and function. This scoping review aimed to summarize the available literature on the association between protein intake and sarcopenia-related outcomes among Korean older adults and identify current research trends and gaps in this field. The review followed the 5-step methodological framework developed by Arksey and O’Malley for scoping reviews and adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews checklist to ensure a comprehensive search strategy. Protein intake was assessed using various methods, including grams per day, grams per kilogram of body weight per day, and intake quartiles. Sarcopenia-related outcomes were categorized into 3 domains as follows: muscle mass, strength, and physical performance. Although most intervention studies demonstrated improvements in muscle mass following protein supplementation, findings on muscle strength and physical function were inconsistent. Cross-sectional studies generally reported better sarcopenia-related outcomes with higher protein intake, particularly when the intake was expressed relative to body weight or analyzed according to quartiles. However, heterogeneity in protein intake assessments and variations in sarcopenia definitions could have contributed to the inconsistent findings across studies. This review highlights the need for applying standardized approaches for protein intake measurement and sarcopenia diagnosis. Future studies should consider the quantity, quality, and timing of protein intake while also focusing on the implementation of integrated, multidisciplinary intervention strategies to promote healthy aging among Korean older adults.

-

Keywords: Protein; Sarcopenia; Korea; Aged; Scoping review

INTRODUCTION

Sarcopenia, marked by age-related declines in skeletal muscle mass and function [

1], has emerged as a growing public health concern [

2], particularly in countries with rapidly aging populations, such as Korea. Adequate protein intake has been widely recognized as a key modifiable factor in the prevention and management of sarcopenia [

3]. However, data from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) indicate that protein intake among many older adults falls below the recommended levels [

4]. Recently, an increasing number of studies in Korea have investigated the association between muscle health and various aspects of protein intake, including total amount, quality, and source. Nonetheless, no comprehensive synthesis has been conducted to elucidate the scope, nature, and characteristics of these studies among Korean older adults.

A scoping review is particularly useful for systematically organizing and mapping existing literature in research fields that study broad topics and inconsistently apply concepts or definitions [

5]. Accordingly, this study employed a scoping review methodology to comprehensively examine studies that investigated the association between protein intake and sarcopenia or related indicators among Korean older adults. The specific objectives of the current study were to (1) identify the key characteristics of studies in this field, namely the study design, methods for assessing protein intake, outcome measures, and definitions of sarcopenia; (2) explore how protein intake variables were operationalized and analyzed; and (3) summarize the main findings and identify knowledge gaps to inform future research and practice.

By addressing these objectives, this review aims to provide an overview of current evidence and research trends, highlight areas for further investigation, and promote the development of nutritional strategies tailored to prevent sarcopenia among Korean older adults.

METHODS

Protocol

This scoping review was conducted using the following 5-step methodological framework developed by Arksey and O’Malley [

6]: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) selecting studies; (4) charting the data; (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. The review process was reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension (PRISMA) for Scoping Reviews guidelines [

7].

This review was guided by the following research questions: (1) What do existing studies reveal about the association between protein intake and sarcopenia-related indicators among Korean older adults? (2) What are the current research trends and areas for future research?

Identifying relevant studies

The current search strategy was adopted from our previous systematic review and meta-analysis on the same topic [

8]. A comprehensive literature search was conducted across 6 electronic databases, namely MEDLINE via PubMed, Embase, Cochrane, KoreaMed, RISS, and ScienceON, as well as through manual screening of reference lists from relevant articles. Two researchers (Minjee Han and Kyung-sook Woo) independently searched the databases for studies published up to September 2022.

The search was performed based on predefined Population, Intervention (or Exposure), Comparison, Outcome, and Study Design (PICOS) criteria and included a broad range of search terms related to “protein intake” and “sarcopenia” to better reflect the scope of the review. For the population, search terms such as “aged,” “elder*,” “older*,” and “Korea” were used to identify studies on Korean older adults. For the intervention or exposure, terms such as “protein*,” “amino acid*,” “leucine,” “BCAA,” “HMB,” and related compounds were used. To determine sarcopenia-related outcomes, search terms such as “muscle mass,” “muscle strength,” “physical performance,” “gait speed,” “hand grip strength,” “SPPB,” “TUG,” “sarcopenia,” and “frailty” were used.

Supplementary Table 1 presents a complete list of search terms and Boolean combinations, which were selected based on a previously published systematic review on a related topic [

9]. Medical Subject Headings and Entree terms were also used to search titles and abstracts. Considering that this study focused on Korean older adults, the search was restricted to studies on humans published in Korean or English. All study designs were included in the review.

Study selection

The screening process involved an initial review of the titles and abstracts, followed by full-text screenings by 2 independent researchers. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined based on the pre-established PICOS framework. Any disagreements in study selection were resolved through discussion and consensus.

Studies that satisfied any of the following criteria were included in the analysis: (1) studies including participants aged ≥ 65 years and residing in Korea; (2) those that reported protein or amino acid intake levels; and (3) those that included sarcopenia or sarcopenia-related indicators as outcome measures.

Studies that met any of the following criteria were excluded: (1) those conducted on non-Korean populations; (2) those that included participants < 65 years of age; (3) those that focused on interventions unrelated to protein; (4) those that failed to report outcomes related to sarcopenia; (5) case reports, abstracts only, qualitative studies, literature reviews, or systematic reviews with meta-analyses; and (6) those published in languages other than Korean or English.

Charting the data

Data charting was conducted by one reviewer using Microsoft Excel and verified by a second reviewer. The following data were extracted from the included studies: author, first author’s affiliation, year of publication, journal of publication, study population, sample size, data source, study design, study duration, type of exposure variable, outcome variables, methods of outcome measurement, and key findings relevant to the review topic.

Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

After data charting, a narrative synthesis was performed to summarize the key findings. Studies examining the association between protein intake and sarcopenia or related indicators were systematically categorized. Thereafter, key results from each study were summarized, and emerging trends or patterns across studies were identified and reported. Data were visually presented using tables and graphs. Subsequently, the implications of the findings were discussed, and recommendations for future research were provided.

RESULTS

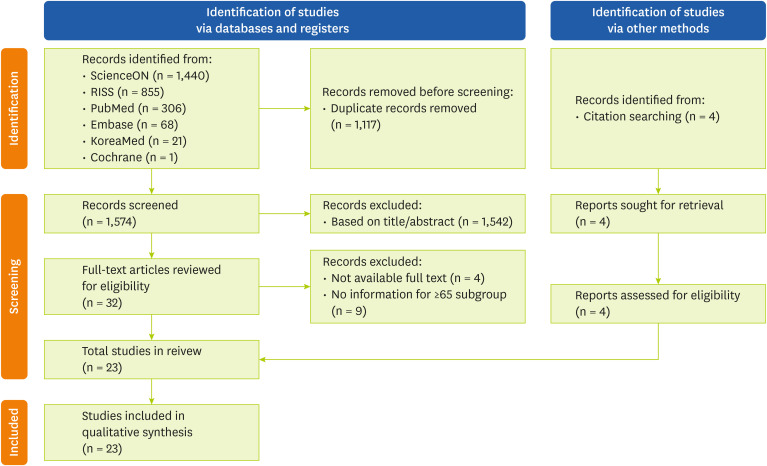

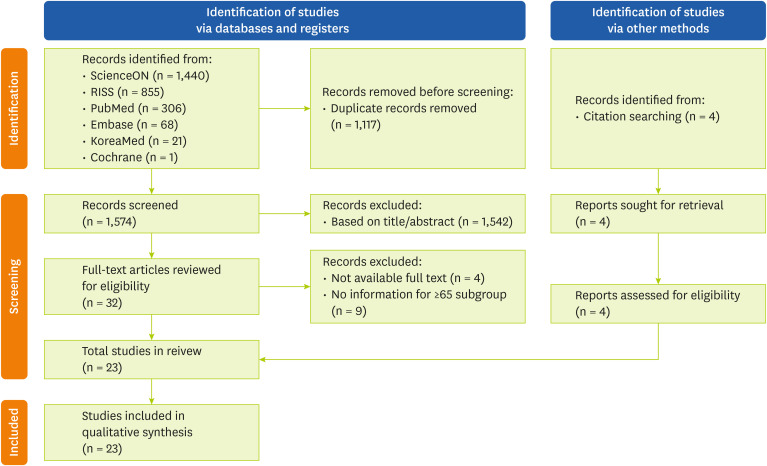

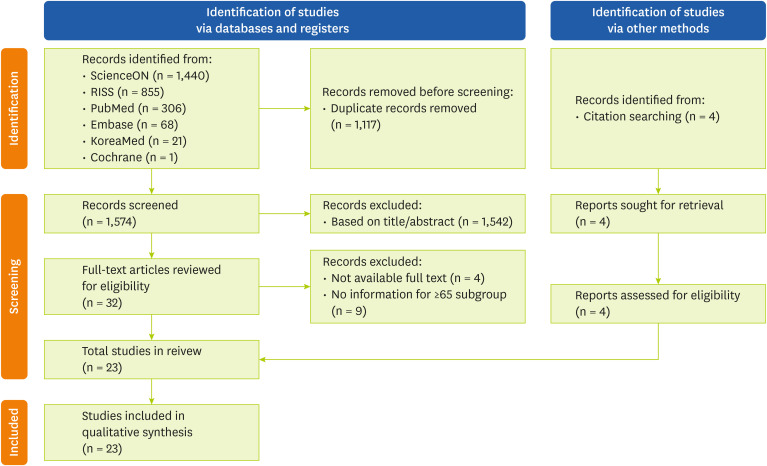

After searching all 6 databases, a total of 2,691 articles were retrieved, from which 1,117 duplicates were removed. An initial screening of the titles and abstracts of the remaining 1,574 articles resulted in the further exclusion of 1,542 studies. A full-text review was conducted for 32 articles, of which 4 were excluded due to lack of full-text availability and 9 were excluded for not including participants aged ≥ 65 years. Four additional studies were identified through citation searching. Thus, 23 studies were included in the final analysis. The study selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (

Figure 1).

Figure 1 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2020 flow diagram for study selection.

Characteristics of the included studies

To assess the publication trends over time, the publication year of each study was analyzed. Notably, one study (4.3%) was published before 2000 and another (4.3%) between 2001 and 2010. Research activity increased substantially after 2011, with 11 studies (47.8%) published from 2011 to 2020 and 10 studies (43.5%) published since 2021. In terms of study design, 5 studies (21.7%) were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 2 (8.7%) were non-RCTs, and 16 (69.6%) were cross-sectional studies. Among the included studies, 14 used data from the KNHANES; 1 study focused on patients, and another was community-based (

Supplementary Figure 1).

To identify the academic fields that primarily conducted studies on the association between protein intake and sarcopenia, we analyzed the institutional affiliations of the first authors and the academic disciplines of the journals in which the studies were published. Based on the first authors’ affiliations, 9 studies (39.1%) were conducted in the Food and Nutrition departments of their respective universities, whereas 4 (17.4%) were conducted in other departments, such as Medical Nutrition and Physical Education. Moreover, 5 studies (21.7%) were conducted in university hospitals, among which 2 were conducted in the Family Medicine department and one each in the Orthopedics, Rehabilitation, and Nursing departments. Additionally, 3 studies (13.0%) were conducted at research institutes, and one study each was conducted at a community healthcare center and a medical center (

Table 1).

Table 1Classification of institutional affiliations

Table 1

|

Institutional affiliations of the first author |

References |

No. (%) |

|

University |

|

|

|

Department of Food Science and Nutrition |

[9, 11, 13, 17, 22, 27, 28, 30, 31] |

9 (39.1) |

|

Department of Medical Nutrition |

[26] |

1 (4.3) |

|

Department of Physical Education |

[12] |

1 (4.3) |

|

Departments not specified |

[14, 15] |

2 (8.7) |

|

University hospital |

|

|

|

Department of Family Medicine |

[18, 29] |

2 (8.7) |

|

Department of Orthopedic Surgery |

[23] |

1 (4.3) |

|

Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation |

[25] |

1 (4.3) |

|

Department of Nursing |

[21] |

1 (4.3) |

|

Others |

|

|

|

Research institute |

[19, 20, 24] |

3 (13.0) |

|

Community health center |

[10] |

1 (4.3) |

|

Medicine center |

[16] |

1 (4.3) |

The journals in which the studies were published were classified into 5 categories based on their primary academic focus: nutrition, geriatrics, sports science, bone metabolism, and others. Among the analyzed studies, 11 (47.8%) were published in nutrition-related journals; 3 (13.0%) each were published in geriatrics and bone metabolism journals; 2 (8.7%) were published in sports science journals; 4 (17.4%) were published in multidisciplinary journals covering broader fields, such as integrative medicine, growth and development, and public health; and 3 were classified as “others” (

Supplementary Table 2).

Table 2 summarizes the protein intake variables presented in each study. All seven interventional studies involved the provision of additional protein at varying quantities. Protein supplementation was administered as an oral nutritional supplement in 3 studies [

10,

11,

12], powder or packets in another 3 studies [

13,

14,

15], and milk and boiled eggs in one study [

16]. Some studies also incorporated resistance training into their intervention [

15,

16]. In certain cases, the exact amount of protein provided could not be estimated [

10].

Table 2Categorization of protein intake variables

Table 2

|

Type of protein intake variables and exercise status |

References |

|

Intervention study |

|

|

ONS (new care 500 mL/day) with no exercise |

[9] |

|

ONS (400 kcal, 25 g of protein; 9.4 g of essential amino acids) with no exercise |

[10] |

|

ONS (200 mL/day, 200 kcal, 15 g of protein, with some micronutrients) with no exercise |

[11] |

|

20 g/day of whey protein and 15 g/day of soybean protein, including 3 g of branched-chain amino acids with no exercise |

[12] |

|

200 kcal/day,0.5 g of fat, 0.2 g of cocoa powder, 9.3 g of whey protein/10 g pack with no exercise |

[13] |

|

47 g/day whey protein isolate and certain micronutrients with resistance training |

[14] |

|

200 mL of milk +1 boiled egg (50 g) with resistance training |

[15] |

|

Cross-sectional study |

|

|

Protein intake (g/kg/day) |

[16, 17, 18, 19, 20] |

|

Protein intake (g/day) |

[21, 22, 23, 24] |

|

Protein intake (g/kg/day) per 1 increment |

[18] |

|

Low dietary protein intake (< 55 and < 45 g/day in men and women, respectively) |

[23] |

|

Inadequate protein intake (< 45 and < 40 g/day in men and women, respectively) |

[25] |

|

Insufficient protein intake (< 0.91 g/kg/day) |

[26] |

|

Quartile of protein intake (g/day) |

[27, 28] |

|

Quartile of protein intake (g/kg/day) |

[29] |

|

Quartile of animal and plant protein intake |

[27] |

|

Quartile of branched-chain amino acid intake (g/day) |

[30] |

|

Quartile of essential amino acid score (meeting the RNI for each essential amino acid) |

[31] |

Cross-sectional studies presented daily protein intake in various forms. Specifically, 5 studies analyzed protein intake in terms of grams per kilogram of body weight per day (g/kg/day) [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21], whereas 4 studies expressed it in terms of grams per day (g/day) without considering body weight [

22,

23,

24,

25]. Some studies examined the association between protein intake and sarcopenia by comparing individuals consuming protein below a specific threshold [

24,

26,

27], whereas others analyzed intake based on quartiles [

28,

29,

30]. Additionally, one study differentiated between animal and plant protein intake [

28], whereas another considered branched-chain amino acids and essential amino acids (EAA) as the primary variables [

31,

32].

Sarcopenia assessment

Various indicators have been used to assess sarcopenia (

Table 3). The 3 domains commonly included in international diagnostic criteria—muscle mass, muscle strength, and physical performance—were frequently applied. These indicators were used individually or in combination to evaluate sarcopenia and its association with protein intake.

Table 3Categorization of reported measures used in the assessment of sarcopenia and related indicators

Table 3

|

Measurement indicators |

References |

|

Muscle mass-related |

|

|

ASM |

|

|

|

ASM (kg) |

[11, 13] |

|

|

ASM/Wt (%) |

[13, 16, 17, 19, 21, 22, 26, 29] |

|

|

ASM/Ht2 (kg/m2) |

[11, 13, 23, 24, 28] |

|

|

ASM/BMI |

[13, 18] |

|

|

ASM:fat ratio |

[13] |

|

Lean mass |

|

|

|

Lean body mass (kg) |

[9, 11] |

|

Muscle mass |

|

|

|

Muscle mass (g, kg) |

[14, 15, 17] |

|

|

Muscle mass (kg/m2) |

[24] |

|

|

Skeletal muscle mass (kg) |

[12] |

|

|

Low skeletal muscle mass index |

[18] |

|

|

Weight-adjusted low muscle mass |

[29] |

|

HGS-related (muscle strength) |

|

|

HGS (kg) |

[10, 11, 13, 24, 28, 30] |

|

HGS/Wt (kg) |

[12] |

|

Low HGS (odds ratio) |

[25, 27] |

|

High HGS |

[31] |

|

Relative grip strength (HGS/Wt * 100) |

[20] |

|

Physical function-related |

|

|

Short Physical Performance Battery score |

[10, 12, 13] |

|

Gait speed (m/s) |

[10, 12, 13, 28] |

|

Timed up-and-go test (s) |

[10, 13] |

|

One-legged stance (s) |

[10] |

|

Balance test |

[12, 13] |

|

Sit-to-stand (s) |

[13] |

|

Chair stand (s) |

[12] |

|

Physical activity (kcal/week) |

[13] |

|

Physical functioning |

[10] |

|

Others |

|

|

Frailty (status, score) |

[11] |

|

Mid upper arm circumference (mm ) |

[9, 10, 11] |

|

Calf circumference (cm) |

[11] |

|

Triceps skinfold (mm) |

[9] |

|

Mid upper arm muscle circumference (cm) |

[9] |

|

Mid upper arm muscle area (cm) |

[9] |

|

Waist to hip ratio |

[15] |

|

Lower body muscular strength: sit-to-stand (repetitions) |

[14] |

|

Upper body muscular strength: dumbbell lift (repetitions) |

[14] |

|

Aerobic endurance: step-in-place (repetitions in 2 min) |

[14] |

|

Lower body flexibility: seated forward bend (cm) |

[14] |

|

Upper body flexibility: behind-the-back hand clasp (cm) |

[14] |

|

Agility and dynamic balance: 2.44-m timed up and go (s) |

[14] |

|

Aging-related hormones (estrogen, growth hormones, and dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate) |

[14] |

Muscle mass was primarily assessed using appendicular skeletal muscle mass (ASM), reported in various forms, including ASM (kg), ASM/Wt (%), ASM/Ht2 (kg/m2), ASM/ body mass index (BMI), and ASM:fat ratio. Some studies measured lean body mass or skeletal muscle mass, whereas others referred generally to “muscle mass” without specifying the type, which complicated the determination of the exact measurement used. Alternative indicators, such as low skeletal muscle mass index and weight-adjusted low muscle mass, were also reported.

Muscle strength was most commonly assessed using handgrip strength (HGS), with indicators including low, high, and relative HGS. Physical performance was typically evaluated using established functional tests, such as the Short Physical Performance Battery score, gait speed, Timed Up and Go (TUG) test, and balance tests. In addition to these core indicators, some studies assessed frailty status, mid-upper arm circumference, and calf circumference.

Diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia

Among the 23 studies analyzed, 9 used sarcopenia as a primary outcome measure, applying various diagnostic criteria (

Table 4). Several studies commonly used the diagnostic components (i.e., muscle mass, muscle strength, and physical performance) proposed by international guidelines, such as the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS) [

33] and the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) [

2]. However, only a few studies assessed all 3 components.

Table 4Diagnostic criteria and cutoff values for sarcopenia and related conditions

Table 4

|

Author |

Data source |

Muscle mass |

Muscle strength |

Physical performance |

Additional criteria |

|

ASM index |

Cutoff criteria |

Method |

|

Sarcopenia |

|

Bae and Kim (2017) [17] |

KNHANES 2008–2011 |

ASM/Wt (%) |

< 1 SD below the mean of healthy young individuals with no chronic disease (20–39 yr) |

DXA |

NA |

NA |

N/A |

|

Lim et al. (2018) [23] |

KNHANES 2008–2011 |

ASM/Wt (%) |

< 1 SD below the mean of healthy young individuals with no chronic disease (20–39 yr) |

DXA |

NA |

NA |

N/A |

|

Yoo et al. (2020) [27] |

KNHANES 2008–2011 |

ASM/Wt (%) |

< 1 SD below the mean of healthy young individuals with no chronic disease (20–39 yr) |

DXA |

NA |

NA |

N/A |

|

Na et al. (2022) [20] |

KNHANES 2008–2011 |

ASM/Wt (%) |

< 1 SD below the mean of healthy young individuals with no chronic disease (19–39 yr) |

DXA |

NA |

NA |

N/A |

|

Kim et al. (2014) [22] |

KNHANES 2010–2011 |

ASM/Wt (%) |

< 2 SD below the mean of young healthy ;individuals with no chronic disease (20–39 yr) |

DXA |

NA |

NA |

N/A |

|

Huh and Son (2022) [30] |

KNHANES 2008–2011 |

ASM/Wt (%) |

< 2 SD below the mean of young healthy individuals with no chronic disease (20–39 yr) |

DXA |

NA |

NA |

N/A |

|

Yoo et al. (2020) [24] |

KNHANES 2008–2011 |

ASM/Ht (kg/m2) |

< 7.0 in men, < 5.4 in women (according to the AWGS 2014) |

DXA |

NA |

NA |

N/A |

|

Choi et al. (2022) [25] |

Care facility |

ASM/Ht (kg/m2) |

< 7.0 in men, < 5.4 in women (according to the AWGS 2014) |

DXA |

HGS < 26 kg in men, < 18 kg in women |

NA |

N/A |

|

Park et al. (2022) [29] |

Community-based |

ASM/Ht (kg/m2) |

< 7.0 in men, < 5.4 in women (according to the AWGS 2014) |

DXA |

HGS < 26 kg in men, < 18 kg in women |

Gait speed ≤ 0.8 m/s |

N/A |

|

Sarcopenic obesity |

|

Lim et al. (2018) [23] |

KNHANES 2008–2011 |

ASM/Wt (%) |

< 1 SD below the mean of healthy young individuals with no chronic disease (20–39 yr) |

DXA |

NA |

NA |

WC > 85 cm in women, > 90 cm in men |

|

Yoo et al. (2020) [27] |

KNHANES 2008–2011 |

ASM/Wt (%) |

< 1 SD below the mean of young healthy individuals with no chronic disease (20–39 yr) |

DXA |

NA |

NA |

BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2

|

|

Yoo et al. (2020) [24] |

KNHANES 2008–2011 |

ASM/Ht (kg/m2) |

< 7.0 in men, < 5.4 in women (according to the AWGS 2014) |

DXA |

NA |

NA |

BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2

|

|

Lee et al. (2021) [19] |

KNHANES 2008–2011 |

ASM/BMI |

< 0.789 in men, < 0.512 in women |

DXA |

NA |

NA |

BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2

|

|

Osteosarcopenia |

|

Yoo et al. (2020) [24] |

KNHANES 2008–2011 |

ASM/Ht (kg/m2) |

< 7.0 in men, < 5.4 in women (according to the AWGS 2014) |

DXA |

NA |

NA |

BMD < 2.5 SD below peak bone mass of a young health group |

Additionally, the cutoff values used by the studies varied depending on the criteria adopted. Seven studies defined sarcopenia based solely on muscle mass. Meanwhile, 4 studies defined sarcopenia as a reduction in ASM to below 1 standard deviation (SD) of a younger reference group, adjusted for body weight [

17,

20,

23,

27], whereas 2 studies used a cutoff of 2 SD below the reference group [

22,

30]. One study applied a height-adjusted ASM consistent with the AWGS criteria [

24].

A study conducted in a care facility applied the AWGS 2014 criteria for muscle mass while also assessing HGS [

25]. A community-based study by Park et al. [

29] was the only study to diagnose sarcopenia using all 3 components: muscle mass, muscle strength, and physical performance. Sarcopenia was also examined in the contexts of sarcopenic obesity and osteosarcopenia. Sarcopenic obesity is defined as the coexistence of sarcopenia and obesity, with obesity being determined based on waist circumference or BMI [

19,

23,

24,

27].

Table 5 summarizes the key findings of the included studies regarding the association between protein intake and sarcopenia-related outcomes. Interventional studies frequently observed increases in skeletal muscle mass, lean body mass, and ASM following protein supplementation. In contrast, studies reported inconsistent results for HGS, a commonly used indicator of muscle strength. Some trials reported improvements in physical performance, such as gait speed and the TUG test, particularly when resistance exercise was combined with protein supplementation.

Table 5Summary of study findings on the relationship between protein intake and sarcopenia

Table 5

|

First author (yr) |

Study design (F/U) |

Data source |

Men/women age (yr) |

Protein intake* assessment |

Sarcopenia related indicators assessed |

Main findings |

|

Intervention study |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Han et al. (1997) [10] |

Non-RCT (4 wk) |

Care facility |

0/25 (≥ 65) |

ONS of 500 mL/day |

Mass + Others†

|

Mid-arm circumference and triceps skinfold improved |

|

24-hr recall |

|

Li et al. (2022) [13] |

RCT (8 wk) |

Community-based |

13/11 (≥ 65) |

20 g/day whey + soy |

Strength + Function |

Skeletal muscle mass increased |

|

Not reported |

|

Park (2006) [16] |

Non-RCT (10 wk) |

Community-based |

0/27 (≥ 70) |

200 mL milk+ 50 g egg |

Mass + Others |

Increased muscle mass with resistance training and milk protein supplementation |

|

Not reported |

|

Kim and Lee (2013) [11] |

RCT (12 wk) |

Community-based |

15/69 (≥ 65) |

ONS (25 g/day) |

Strength + Function + Others |

Timed Up and Go test improved |

|

24-hr recall |

|

Kim et al. (2016) [15] |

RCT (12 wk) |

Community-based |

0/23 (65–74) |

47 g/day whey |

Mass + Others |

Muscle mass, flexibility, and hormone levels improved with resistance training and protein |

|

Not reported |

|

Park et al. (2018) [14] |

RCT (12 wk) |

Community-based |

42/78 (70–85) |

10 g/day whey |

Mass + Strength + Function |

Muscle mass indicators (ASM, SMI, ASM/BMI, ASM:fat ratio) and gait speed improved in the higher protein group |

|

3-day record |

|

Na et al. (2021) [12] |

RCT (90 days) |

Community-based |

9/44 (80.5 ± 7.0) |

ONS (15 g/day) |

Mass + Strength + Others |

Lean body mass increased |

|

Dietary record |

|

Cross-sectional study |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bae and Kim (2017) [17] |

- |

KNHANES 2008–2011 |

1,642/2,259 (≥ 65) |

g/kg/day |

Mass only |

Higher risk of sarcopenia in the < 0.8 g/kg/day group than in the ≥ 1.2 g/kg/day group |

|

24-hr recall |

|

Na et al. (2022) [20] |

- |

KNHANES 2008–2011 |

1,414/1,822 (≥ 65) |

g/kg/day |

Mass only |

Higher risk of sarcopenia in men and women with < 0.8 g/kg/day protein intake than in those with ≥ 1.2 g/kg/day protein intake |

|

24-hr recall |

|

Kim et al. (2014) [22] |

- |

KNHANES 2010–2011 |

770/1,000 (≥ 65) |

g/day |

Mass only |

No significant findings in protein intake |

|

24-hr recall |

|

Lim et al. (2018) [23] |

- |

KNHANES 2008–2011 |

1,850/1,642 (≥ 65) |

g/day |

Mass only |

Protein intake was lower in the sarcopenia group than in the sarcopenic obesity group |

|

24-hr recall |

|

Choi et al. (2022) [25] |

- |

Care facility (patients with hip fractures) |

12/35 (≥ 65) |

g/day |

Mass + Strength |

Lower protein intake was associated with lower HGS |

|

FFQ |

|

Yoo et al. (2020) [24] |

- |

KNHANES 2008–2011 |

1,698/2,322 (≥ 65) |

g/day < 55 g/day in men, < 45 g/day in women |

Mass only |

Total protein intake was lower in men and women with sarcopenia than in the normal group and even lower in the osteosarcopenia group. |

|

24-hr recall |

|

Yoo et al. (2020) [27] |

- |

KNHANES 2008–2011 |

401/854 (≥ 65) |

< 0.91 g/kg/day for 24-hr recall |

Mass only |

Higher risk of insufficient protein intake in the sarcopenic obesity group than in the non-sarcopenic obesity group |

|

Lee et al. (2021) [19] |

- |

KNHANES 2008–2011 |

1,635/2,193 (≥ 65) |

g/kg/day per 1 g/kg/day increment |

Mass only |

No association between protein intake and muscle mass; risk for sarcopenic obesity decreased with increased energy and carbohydrate intake |

|

24-hr recall |

|

Park et al. (2022) [29] |

- |

Community-based |

358/416 (70–84) |

g/day quartile |

Mass + Strength + Function |

Lower risk of sarcopenia in the Q4 group than in the Q1 group |

|

24-hr recall |

|

Huh and Son (2022) [30] |

- |

KNHANES 2008–2011 |

358 (gender unknown) (≥ 65) |

g/kg/day quartile |

Mass only |

Higher risk of sarcopenia in the Q1 group than in the Q4 group |

|

24-hr recall |

|

Oh and No (2018) [18] |

- |

KNHANES 2009 |

651/916 (≥ 65) |

g/kg/day |

Mass only |

Protein intake was positively associated with muscle mass but negatively associated with fat mass |

|

24-hr recall |

|

Park et al. (2021) [31] |

- |

KNHANES 2014–2018 |

2,124/2,728 (≥ 65) |

g/day BCAA quartile 24-hr recall |

Strength only |

Leucine intake was positively associated with HGS |

|

Park and Chung (2022) [21] |

- |

KNHANES 2016–2018 |

1,514/0 (68–80) |

g/kg/day |

Strength only |

Higher protein intake in the Q4 relative grip strength group than in the Q1, Q2 and Q3 groups |

|

24-hr recall |

|

Kim et al. (2019) [26] |

- |

KNHANES 2014–2016 |

1,692/1,942 (≥ 65) |

< 45 g/day in men, < 40 g/day in women |

Strength only |

Higher inadequate protein intake in men with low HGS |

|

24-hr recall |

|

Jang and Ryu (2020) [28] |

- |

KNHANES 2016–2018 |

0/2,083 (≥ 65) |

g/day animal, plant quartile |

Strength only |

Lower risk of low HGS in the Q4 animal protein intake group than in the Q1 group |

|

24-hr recall |

|

Im et al. (2022) [32] |

- |

KNHANES 2014–2019 |

2,570/3,401 (≥ 65) |

EAA quartile |

Strength only |

Higher muscle strength in the Q4 EAAS group and Q4 animal-source EAA group than in the Q1 group |

|

24-hr recall |

Cross-sectional studies reported that higher protein intake was generally associated with more favorable outcomes, including higher muscle mass, higher grip strength, and better physical performance. Individuals in the highest protein intake quartiles tended to have higher ASM or muscle strength and a lower risk of sarcopenia than those in the lower protein intake quartiles. Studies examining protein quality, such as intake of animal protein, leucine, or EAA, also frequently reported positive associations with muscle strength, particularly HGS.

The heterogenous findings may be partly explained by methodological differences in the assessment of protein intake and sarcopenia. Studies that measured protein intake relative to body weight (g/kg/day) or analyzed intake by quartiles tended to report more consistent associations with sarcopenia-related outcomes than those using absolute intake (g/day). Most cross-sectional studies that used KNHANES data assessed protein intake based on dietary sources only, typically excluding supplemental intake from total protein calculations. Similarly, the 2 cross-sectional studies not based on KNHANES data either did not mention or excluded protein supplementation.

Inconsistencies in outcome assessment may also have contributed to the variability in findings. In particular, studies that evaluated multiple domains, such as muscle mass along with strength and physical performance, tended to report more consistent associations between protein intake and sarcopenia risk, whereas those assessing only one domain, such as muscle mass, showed more limited results.

DISCUSSION

This scoping review analyzed a diverse range of studies examining the association between protein intake and sarcopenia among Korean older adults. We observed a notable increase in the number of publications since 2011, reflecting the growing recognition of dietary protein as a key factor in the prevention and management of sarcopenia. Most of the included studies employed cross-sectional designs, whereas interventional studies were relatively limited. Moreover, several cross-sectional studies used data from the KNHANES, which is a nationally representative and reliable dataset that enhances the population-level validity of findings. However, the repeated use of the same KNHANES dataset across multiple studies may limit the generalizability of findings and introduce potential overlap among study populations, which should be considered when interpreting the results.

Although most of the first authors were affiliated with the departments of Food and Nutrition, some were also involved in other disciplines, such as medical nutrition, family medicine, rehabilitation medicine, and nursing, highlighting the multidisciplinary interest in the topic. Additionally, the included studies were published in journals covering a wide range of disciplines, including nutrition, geriatrics, sports science, and rehabilitation medicine, indicating that the topic lies at the intersection of multiple disciplines and has been actively explored from diverse professional perspectives. These findings indicate that sarcopenia is increasingly recognized as a critical challenge related to not only aging or nutritional deficiency but also functional independence, quality of life, and chronic disease management.

Considerable heterogeneity in protein intake assessment was observed among the included studies. Notably, interventional studies typically provided protein through supplementation but often overlooked baseline dietary protein intake from habitual meals, limiting the interpretation of the intervention’s effectiveness. In contrast, most cross-sectional studies assessed total protein intake but used various methods for quantifying and categorizing the intake. Some studies reported intake in g/kg/day, whereas others used g/day, categorized participants based on specific intake cutoffs, or divided them into quartiles. These inconsistencies in measurement and classification hinder comparisons among studies. In our previous meta-analysis on this topic, including a sufficient number of studies for data synthesis was challenging because of heterogeneity. Moreover, few studies have considered the qualitative aspects of protein intake, such as the source (animal- vs. plant-based), amino acid composition, or leucine content. Considering the remarkable influence of protein quantity and quality on muscle health in older adults, existing studies appear to rely too heavily on quantitative indicators alone.

Thus, future studies assessing protein intake should move beyond solely focusing on total protein intake and adopt a more integrated approach that incorporates protein quality and intake patterns. The current scoping review revealed a general trend in which higher protein intake was associated with more favorable outcomes in sarcopenia-related indicators, including ASM, HGS, and physical function. These findings align with those of previous studies. Indeed, a meta-analysis conducted specifically among Korean older adults demonstrated that individuals consuming < 0.8 g/kg/day of protein had a remarkably higher risk of sarcopenia than did those consuming ≥ 1.2 g/kg/day. Based on this evidence, a minimum protein intake of 0.8 g/kg/day has been recommended for Korean older adults [

8].

However, the included studies presented considerable heterogeneity in the definitions and assessment criteria for sarcopenia and related components. Although several studies adopted criteria from established groups, such as the AWGS or EWGSOP, some applied only parts of these guidelines or introduced modifications. In other cases, sarcopenia was diagnosed based solely on individual indicators, such as ASM or HGS, without a clearly defined diagnostic framework. Additionally, the studies used varying cutoff values for these indicators, leading to discrepancies in the definition of sarcopenia, despite the common use of the term. Notably, the KNHANES, which has been frequently used in cross-sectional studies, provides nationally representative and reliable data.

However, the discontinuation of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry for muscle mass measurements limits current analyses aiming to include this parameter. Inconsistencies in the definition and measurement of sarcopenia further complicate the comparison and interpretation of study findings, highlighting the need for standardized diagnostic criteria and assessment tools in future research.

Although these findings align with those of previous studies suggesting a beneficial role of protein intake, the lack of statistical significance in some studies may reflect differences in study design, sample size, or intervention duration. These differences may be attributed to the relatively short intervention periods in some trials and the absence of combined exercise interventions, which have been considered essential in sarcopenia management. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that whey protein supplementation, particularly when combined with resistance training, remarkably improved muscle mass, strength, and physical performance in older adults diagnosed with sarcopenia based on the EWGSOP or AWGS criteria [

34]. Notably, cross-sectional and observational studies have an inherently limited ability to establish causality, making it difficult to conclude whether protein intake directly prevents or ameliorates sarcopenia. Although a positive association has been consistently observed, inconsistencies in statistical significance and effect sizes highlight the need for more studies employing robust study designs, including long-term follow-up and multimodal interventions incorporating exercise.

Korean older adults tend to have relatively low protein intake because of their predominantly plant-based dietary patterns and consumption of protein mainly during specific meals. These characteristics limit the direct applicability of findings from Western populations to the Korean context. Although several international scoping reviews have examined the effects of protein supplementation and exercise on sarcopenic obesity—highlighting the general benefits of resistance training and whey protein as well as inconsistencies in intervention protocols [

35]—no scoping review has specifically focused on the association between protein intake and sarcopenia among Korean older adults. To address this gap, the current review exclusively focused on studies conducted in Korea to identify research trends and gaps in evidence. This approach provides a valuable foundation for future research and supports the development of context-specific nutritional strategies tailored to the needs and characteristics of Korea’s aging population.

Several limitations have been identified based on the findings of this scoping review. First, most of the included studies were observational or cross-sectional in design, limiting our ability to draw causal inferences. Second, substantial heterogeneity was observed in the measurement and reporting of protein intake as well as in the diagnostic criteria and cutoff values used to define sarcopenia and its components. Third, numerous interventional studies lacked standardized protocols and did not incorporate concurrent physical activity, which is a critical component of effective sarcopenia management.

Considering these limitations, future studies should adopt more standardized methodologies and pursue well-designed, multidisciplinary interventions. In particular, there is a need for (1) standardized metrics for protein intake, including total intake, distribution, and timing; (2) harmonized diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia and consistent use of core outcome indicators; (3) more longitudinal and interventional studies to strengthen causal inference; (4) a more comprehensive exploration of protein quality, including leucine content and plant- vs. animal-based sources; (5) consideration of combined factors, such as physical activity and overall nutritional status; and (6) multidisciplinary collaboration among experts in nutrition, geriatrics, exercise science, and rehabilitation, reflecting the broad relevance of sarcopenia and protein intake across fields.

Some limitations inherent to the scoping review methodology should be acknowledged. This scoping review did not assess the methodological quality or risk of bias of the included studies, which may affect the strength of the conclusions. Moreover, despite conducting a comprehensive database search, relevant gray literature may have been overlooked, and the inclusion of only peer-reviewed articles could have introduced publication bias. Additionally, this review excluded qualitative studies, narrative reviews, and systematic reviews with meta-analyses and focused exclusively on original studies reporting quantitative data to clarify measurement methods for protein intake and sarcopenia while avoiding data duplication. However, future reviews should include a broader range of study designs to provide more comprehensive insights.

CONCLUSION

This scoping review summarized the existing literature on the association between protein intake and sarcopenia-related indicators among Korean older adults and identified current research trends and gaps. Despite the generally positive association between protein intake and sarcopenia-related indicators, the heterogeneity of measurement methods and diagnostic criteria limited the comparability of the included studies.

Future studies should focus on standardizing the definitions and measurement protocols for sarcopenia and on conducting well-designed studies that consider the quantity, quality, and timing of protein intake. Considering the multidisciplinary interest in this field, collaborative efforts across disciplines are essential for developing integrated intervention strategies that can be effectively translated into clinical practice.

National Research Foundation of Koreahttps://doi.org/10.13039/501100003725

NRF 2021R1I1A3049883

NOTES

-

Funding: This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF 2021R1I1A3049883).

-

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

-

Author Contributions:

Conceptualization: Kim K.

Formal analysis: Han M, Woo KS.

Funding acquisition: Kim K.

Methodology: Han M, Woo KS.

Supervision: Kim K.

Writing - original draft: Han M.

Writing - review & editing: Woo KS, Kim K.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary Table 1

Summary of search strategies used to extract relevant data from the databases: full PubMed search strategy and adaptations for other databases

cnr-14-216-s001.xls

Supplementary Figure 1

Overview of study designs and publication years (bar chart) as well as data sources of the cross-sectional studies (pie chart).

cnr-14-216-s003.ppt

REFERENCES

- 1. Larsson L, Degens H, Li M, Salviati L, Lee YI, et al. Sarcopenia: aging-related loss of muscle mass and function. Physiol Rev 2019;99:427-511.

- 2. Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyère O, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019;48:16-31.

- 3. Jung HW, Kim SW, Kim IY, Lim JY, Park HS, et al. Protein intake recommendation for Korean older adults to prevent sarcopenia: expert consensus by the Korean geriatric Society and the Korean Nutrition Society. Ann Geriatr Med Res 2018;22:167-175.

- 4. Park HA. Adequacy of protein intake among Korean elderly: an analysis of the 2013-2014 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data. Korean J Fam Med 2018;39:130-134.

- 5. Mak S, Thomas A. An introduction to scoping reviews. J Grad Med Educ 2022;14:561-564.

- 6. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19-32.

- 7. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, et al. PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467-473.

- 8. Han M, Woo K, Kim K. Association of protein intake with sarcopenia and related indicators among Korean older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2024;16:4350.

- 9. Tu DY, Kao FM, Tsai ST, Tung TH. Sarcopenia among the elderly population: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Healthcare (Basel) 2021;9:650.

- 10. Han KH, Jung EH, Cho SJ. The effectiveness and preferences of nutritional supplementary drinks for the elderly. Korean J Community Nutr 1997;2:366-375.

- 11. Kim CO, Lee KR. Preventive effect of protein-energy supplementation on the functional decline of frail older adults with low socioeconomic status: a community-based randomized controlled study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2013;68:309-316.

- 12. Na W, Kim J, Kim H, Lee Y, Jeong B, et al. Evaluation of oral nutritional supplementation in the management of frailty among the elderly at facilities of community care for the elderly. Clin Nutr Res 2021;10:24-35.

- 13. Li X, Kim HJ, Kim DY, Zhang Y, Seo JW, et al. Effects of protein intake on sarcopenia prevention and physical function of the elderly in a rural community of South Korea during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Korean Soc Integr Med 2022;10:37-47.

- 14. Park Y, Choi JE, Hwang HS. Protein supplementation improves muscle mass and physical performance in undernourished prefrail and frail elderly subjects: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2018;108:1026-1033.

- 15. Kim Y, Jeong C, Kang H. The effect of elastic resistance exercise and protein intake on functional fitness and aging hormone in elderly women. J Korean Soc Study Phys Educ 2016;21:111-124.

- 16. Park JH. Effect of the light resistance training and supplemental milk-protein on lipid and bone metabolism marker in over 70yrs women. J Sport Leis Stud 2006;28:311-321.

- 17. Bae EJ, Kim YH. Factors affecting sarcopenia in Korean adults by age groups. Osong Public Health Res Perspect 2017;8:169-178.

- 18. Oh C, No JK. Appropriate protein intake is one strategy in the management of metabolic syndrome in Korean elderly to mitigate changes in body composition. Nutr Res 2018;51:21-28.

- 19. Lee JH, Park HM, Lee YJ. Using dietary macronutrient patterns to predict sarcopenic obesity in older adults: a representative Korean nationwide population-based study. Nutrients 2021;13:4031.

- 20. Na W, Oh D, Hwang S, Chung B, Sohn C. Association between sarcopenia and energy and protein intakes in community-dwelling elderly. Korean J Community Nutr 2022;27:286-295.

- 21. Park MY, Chung NN. Comparison of physical activity and nutrient intake according to relative-grip strength in pre-elderly and elderly men: data from the seventh Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey VII(2016-2018). Korean J Growth Dev 2022;30:245-253.

- 22. Kim HH, Kim JS, Yu JO. Factors contributing to sarcopenia among community-dwelling older Korean adults. J Korean Gerontol Nurs 2014;16:170-179.

- 23. Lim HS, Park YH, Suh K, Yoo MH, Park HK, et al. Association between sarcopenia, sarcopenic obesity, and chronic disease in Korean elderly. J Bone Metab 2018;25:187-193.

- 24. Yoo JI, Lee KH, Choi Y, Lee J, Park YG. Poor dietary protein intake in elderly population with sarcopenia and osteosarcopenia: a nationwide population-based study. J Bone Metab 2020;27:301-310.

- 25. Choi KA, Heu E, Nam HC, Park Y, Kim D, et al. Relationship between low muscle strength, and protein intake: a preliminary study of elderly patients with hip fracture. J Bone Metab 2022;29:17-21.

- 26. Kim CR, Jeon YJ, Jeong T. Risk factors associated with low handgrip strength in the older Korean population. PLoS One 2019;14:e0214612.

- 27. Yoo S, Kim DY, Lim H. Sarcopenia in relation to nutrition and lifestyle factors among middle-aged and older Korean adults with obesity. Eur J Nutr 2020;59:3451-3460.

- 28. Jang W, Ryu HK. Association of low hand grip strength with protein intake in Korean female elderly: based on the seventh Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES VII), 2016–2018. Korean J Community Nutr 2020;25:226-235.

- 29. Park SJ, Park J, Won CW, Lee HJ. The inverse association of sarcopenia and protein-source food and vegetable intakes in the Korean elderly: the Korean frailty and aging cohort study. Nutrients 2022;14:1375.

- 30. Huh Y, Son KY. Association between total protein intake and low muscle mass in Korean adults. BMC Geriatr 2022;22:319.

- 31. Park S, Chae M, Park H, Park K. Higher branched-chain amino acid intake is associated with handgrip strength among Korean older adults. Nutrients 2021;13:1522.

- 32. Im J, Park H, Park K. Dietary essential amino acid intake is associated with high muscle strength in Korean older adults. Nutrients 2022;14:3104.

- 33. Chen LK, Woo J, Assantachai P, Auyeung TW, Chou MY, et al. AWGS: 2019 consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020;21:300-307.e2.

- 34. Li ML, Zhang F, Luo HY, Quan ZW, Wang YF, et al. Improving sarcopenia in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of whey protein supplementation with or without resistance training. J Nutr Health Aging 2024;28:100184.

- 35. Cheah KJ, Cheah LJ. Benefits and side effects of protein supplementation and exercise in sarcopenic obesity: a scoping review. Nutr J 2023;22:52.