ABSTRACT

Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) often present with selective eating behaviors and dietary imbalances, which contribute to nutritional deficiencies that can adversely impact growth and development. Despite increasing awareness of the role of nutrition in ASD management, existing nutritional interventions frequently fail to accommodate the unique dietary needs of this population. This study aimed to develop tailored nutritional counseling materials for ASD children by adapting the food exchange list framework originally designed for individuals with diabetes. A comprehensive food database was constructed using data from the Korean Diabetes Association, the Korea Rural Development Administration, and related resources, specifically addressing the dietary habits and nutritional deficiencies observed in ASD children. Representative foods were selected, standardized for exchange units, and visually documented through photographs to enhance usability. These elements were integrated into a practical, visually engaging educational brochure, which includes detailed food exchange unit tables, photographic representations of portion sizes, and portion standards to guide caregivers in meal planning. The materials focus on enhancing dietary diversity, correcting common nutrient deficiencies, and fostering balanced eating habits. However, limitations exist in adapting a diabetes-centric framework, which may not fully capture the unique dietary preferences and challenges of ASD children. Nevertheless, the developed materials provide a valuable resource for nutritional education and intervention, supporting the health and development of ASD children. Further research is required to refine these materials and evaluate their effectiveness across diverse settings and populations.

-

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder; Food preferences; Diet therapy

INTRODUCTION

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a lifelong neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by dysfunction in the functional domain such as social behavior, communication abilities, restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped behavior patterns [

1]. The prevalence of ASD is continuously increasing worldwide, and according to Statistics Korea, the prevalence rate of ASD children aged 0–9 in 2024 was 4.8 per 1,000 people, with a significant increase particularly among children aged 4–6 (3.5% at age 4, 26.5% at age 5, and 21.6% at age 6) [

2]. This increasing trend is primarily attributed to improved early diagnosis and expanded diagnostic criteria, highlighting the need for systematic intervention approaches.

ASD children exhibit characteristic eating behavior problems along with hypersensitivity to sensory stimulation [

3,

4,

5]. These eating behavior problems manifest in various forms, including selective eating, aggressive eating behavior, picky eating, gluttony of appetite, food spitting, and rejection of new foods [

6]. These issues extend beyond mere behavioral problems and can lead to nutritional imbalance [

3,

4,

5]. Unlike typically developed (TD) children, ASD children are less likely to naturally overcome these biased eating habits during growth [

7,

8], necessitating active intervention to prevent potential developmental delays.

Previous studies have shown that ASD children demonstrate deficiencies in essential nutrients such as vitamin D, vitamin B

12, calcium, with significantly lower intake across food groups compared to TD children [

9]. The eating habits score, as measured by the Brief Autism Mealtime Behavior Inventory score, was significantly higher than that of TD children, with more frequent observations of problematic behaviors such as aggression, rejection of new foods, and repetitive consumption of the same food during meals [

10].

A survey examining the nutritional education needs of parents of ASD children revealed high preference and demand for individualized education [

11]. Given that parents’ knowledge and attitudes as primary caregivers significantly influence children’s proper nutritional intake and dietary habit formation, customized nutritional education for parents is essential.

The food exchange list is a tool for meal planning that categorize foods with similar nutrient content into six food groups (grains, meats, vegetables, fats and oils, milk, and fruits). Foods in each group are standardized to one exchange unit, which provide comparable portions containing similar amounts of energy and macronutrient [

12]. This system enables the design of individualized meal plans that consider factors such as age, sex, medical conditions, and physical activity level, while also promoting both dietary variety and nutritional balance. The food exchange list serves as an evidence-based and practical resource in nutrition education and intervention, particularly for patients.

Initially developed to help individuals with diabetics manage their diets, the food exchange list is now used for nutrition education and management in patients with various conditions. Notably, individuals with obesity can utilize this tool to organize meals that adjust energy intake to meet individual needs, and they can select low-fat options within the meats and milk categories to support weight loss [

13]. Additionally, specialized food exchange lists have been established for patients with renal diseases who require careful monitoring of mineral intake, including sodium, potassium, and phosphorus, enabling appropriate food choices and meal planning [

14]. The effectiveness of the food exchange list in nutrition education has been supported by numerous studies. Kendall and Jansen [

15] (1990) compared nutrient-based education with a food group-based approach using the exchange list among patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Their findings revealed that the exchange list group demonstrated significant improvement in nutritional understanding, highlighting its utility in practical meal planning [

15]. Sidahmed et al. [

16] (2014) developed and implemented a Mediterranean-style food exchange list in a dietary intervention study. The approach led to improved dietary adherence and reductions in both body weight and C-reactive protein levels, underscoring its positive impact on health outcomes [

16]. Multiple additional studies have corroborated these findings [

17,

18].

This study aims to develop customized nutritional counseling materials by adapting the clinically validated food exchange list originally designed for patients with diabetes [

12], while incorporating the specific eating behaviors and nutritional requirements of ASD children. This approach can be particularly valuable in gradually expanding the limited food choices of ASD children and supplementing nutritional deficiencies. The nutritional counseling materials developed through this study are expected to contribute as a practical tool supporting the improvement of nutritional status and healthy development of ASD children.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data collection for food exchange list development

A foundational food exchange list framework was established by analyzing two primary sources: the 'Guidelines for Using Food Exchange lists for Diabetes Meal Planning' from the Korean Diabetes Association (KDA) [

12] and Daejeon St. Mary's Hospital. Basic definitions and concepts of food exchange lists were referenced from the 2020 Dietary Reference Intakes for Koreans (K-DRIs) [

19], and the exact nutrient content of foods was determined using the National Standard Food Composition Table (10th revision) of the Rural Development Administration (RDA) [

20]. From these sources, we constructed an initial database that categorized foods into standardized food groups based on their nutritional composition. Each food group’s classification criteria established by the standard nutrient specifications defined in the diabetic food exchange list, which provided the structural framework for subsequent modifications [

12]. This initial framework served as the basis for further customization to meet the specific needs of ASD children.

To address the limitations of existing diabetes-focused exchange lists that do not distinguish between foods for adults and children, we reviewed studies. Prior studies that investigated food intake in ASD children using Food Frequency Questionnaire, 3-day food records, etc. were included in the review [

4,

21,

22]. In addition, studies that performed meta-analyses of multiple studies were reviewed to increase reliability [

23]. This evaluation included the National Standard Food Composition Table (10th revision) from the RDA [

20]. Foods were included in the database based on the following criteria: frequency of consumption ≥ 1 serving per week in the target population, nutritional value that meets specific deficiency needs, and sensory characteristics appropriate for ASD children. Foods consumed < 1 serving per week were excluded from the final database.

Based on the collected database, foods were classified into six major food groups: grains, proteins, vegetables, fats and oils, milk, and fruits. For each food group, standardized exchange units were established according to their macronutrient content. Within each food group, we selected representative foods based on two primary criteria: foods frequently consumed by children and foods rich in nutrients commonly deficient in ASD children. These representative foods were photographed to visually demonstrate one exchange unit. The photography process was standardized using controlled lighting, a white background, and consistent plating methods to ensure accurate visual estimation of portion sizes. The photographs were incorporated into educational materials along with exchange unit tables. Additionally, we included actual-size references of the tableware used in the photographs to help users accurately estimate portion size.

Development of nutrient source food table

For all foods included in the food exchange list database, we calculated both macro and micronutrient contents based on one exchange unit. This data was organized into comprehensive nutrient source tables to support nutritional intervention education. The nutrient content calculations were based on the RDA’s food composition database [

20]. All foods included in each food group were sorted by nutrient content and then ranked from 1 to 15, excluding foods that are difficult to purchase in the marketplace or difficult for children to consume. These rankings particularly emphasized nutrients commonly deficient in ASD children. The resulting tables were designed to be used in conjunction with the food exchange list, providing a practical tool for addressing specific nutritional deficiencies through food selection.

RESULTS

Database development for food exchange list

The initial food exchange database was established based on two primary sources: the KDA’s food exchange list and Daejeon St. Mary's Hospital's clinical food exchange list. The standardized nutrient criteria for each food group followed the guidelines provided by the KDA's food exchange list (

Table 1). To better accommodate children's dietary preferences and nutritional needs, we supplemented this foundation with additional food items that are commonly consumed by children, assessed by frequency (1 ≥ serving per month) from our previous survey. These additions included items such as ramen, various bread products (twisted bread stick and waffle), cakes, and flavored milk varieties (strawberry, banana, and chocolate). Furthermore, we strategically included nutrient-dense foods like dried kelp (high in potassium and dietary fiber) and webfoot octopus (rich in vitamin D) to address specific nutritional deficiencies common in ASD children (

Table 2).

Table 1Food group and macronutrient component in the food exchange list

Table 1

|

Food group |

No. |

Energy (kcal) |

Carbohydrate (g) |

Protein (g) |

Fat (g) |

|

Total food |

300 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Grains |

46 |

100 |

23 |

2 |

- |

|

Proteins |

82 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Low-fat |

38 |

50 |

- |

8 |

2 |

|

Medium-fat |

28 |

75 |

- |

8 |

5 |

|

High-fat |

16 |

100 |

- |

8 |

8 |

|

Vegetables |

76 |

20 |

3 |

2 |

- |

|

Fats and oils |

31 |

45 |

- |

- |

5 |

|

Milk |

13 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Whole milk |

12 |

125 |

10 |

6 |

7 |

|

Low-fat milk |

1 |

80 |

10 |

6 |

2 |

|

Fruits |

52 |

50 |

12 |

- |

- |

Table 2Additional foods for each food group

Table 2

|

Food group |

Additional foods |

|

Grains |

Soybeans (20), kidney beans (20), ramyeon noodles (40), twisted donuts (kkwabaegi) (25), waffles (35), chocolate cake (25), pancake (35) |

|

Proteins |

|

|

Low-fat |

Webfoot octopus (100) |

|

Vegetables |

Kelp (dried) (20) |

|

Milk |

|

|

Whole milk |

Strawberry flavored milk (200), banana flavored milk (150), chocolate milk (200) |

The resulting comprehensive database systematically categorized a total of 300-foods: 46 grains, 82 proteins (38 low-fat, 28 medium-fat, and 16 high-fat), 76 vegetables, 31 fats and oils, 13 milk (12 whole milk and 1 low-fat milk), and 52 fruits. A detailed list of foods is presented in

Table 3. The nutritional content of each food item was standardized using the RDA’s Food Composition Database (10th version) [

15]. Exchange units were calculated by converting the standard 100g nutritional values according to the established criteria.

Table 3Food composition of food exchange list

Table 3

|

Food group |

Included food list |

|

Grains (n = 46) |

White rice (cooked), barley (cooked), brown rice (cooked), rice porridge (cooked), white rice, barley, Job’s tears, sorghum, foxtail millet, glutinous rice, red beans, brown rice, millet, mung beans, green peas, oats, soybeans, kidney beans, mixed grain powder, wheat flour, garaetteok (cylindrical rice cake), baekseolgi (steamed white rice cake), songpyeon (rice cake with sesame seeds), sirutteok (steamed rice cake), injeolmi (rice cake coated with bean powder), jeolpyeon (sliced rice cake), dried noodles, boiled noodles, fresh udon noodles, dried chewy noodles, fresh knife-cut noodles, dried spaghetti, boiled spaghetti, fresh sweet potato starch noodles, ramen noodles, potato, sweet potato, fresh glutinous corn, acorn jelly, corn, dried scorched rice, chestnut, oatmeal, ginkgo nut, cornflakes, white bread |

|

Proteins (n = 82) |

|

|

Low-fat (n = 38) |

Chicken (breast), pork (loin), beef (shank), beef (round), duck meat, beef jerky, flounder, halibut, cod, frozen pollock, butterfish, salmon, yellow croaker, cuttlefish, semi-dried pollock, dried shredded squid, dried yellow corvina, dried pollock, anchovy, whitebait, filefish fillet, steamed fish cake, imitation crab meat, salted pollock roe, cockle, blue crab, octopus minor, flying fish roe, octopus, squid, sea squirt, shrimp (medium-sized), shrimp (large-sized), abalone, mussel, sea cucumber, sea pineapple, webfoot octopus |

|

Mid-fat (n = 28) |

Chicken (with skin), pork (tenderloin), beef (sirloin), beef (tenderloin), beef (brisket), salad ham, cutlassfish, mackerel, pacific saury, croaker, Spanish mackerel, Atka mackerel, eel, horse mackerel, gizzard shad, herring, semi-dried saury, smelt, smoked salmon, fried fish cake, egg, quail egg, black beans, yellow soybeans, firm tofu, soft tofu, silken tofu, soybean curd residue |

|

High-fat (n = 16) |

Pork ribs, bacon, Vienna sausage, frankfurter sausage, beef ribs, oxtail, pork belly, canned mackerel, canned Pacific saury, canned tuna, cheddar cheese, ricotta cheese, mozzarella cheese, gouda cheese, cream cheese, fried tofu |

|

Vegetables (n = 76) |

Korean wild chive (gomchi), eggplant, sweet potato stems, bracken (boiled), chili leaves, perilla leaves, ripe pumpkin (raw), pickled radish (danmuji), sweet pumpkin, wild garlic (dallae), carrot, green onion, bellflower root (doraji), sedum (dolnamul), water dropwort (Minari), garlic, garlic scapes, butterbur, radish, dried radish strips, boiled radish greens, leek, napa cabbage, red cabbage, broccoli, lettuce, celery, bean sprouts, spinach, mugwort, crown daisy, mallow, zucchini, cabbage, iceberg lettuce, onion, young radish greens, cucumber, lotus root, burdock root, daylily (wonchuri), bamboo shoots (raw), bamboo shoots (canned), chamnamul (Pimpinella brachycarpa), bok choy, dried chwinamul (wild greens), chicory, kale, cauliflower, soybean sprouts, bell pepper, green chili, green garlic, sweet pepper, konjac, laver (gim), seaweed (maesaengi), seaweed (raw), seaweed (hijiki, raw), agar jelly, seaweed (paraeseaweed, raw), dried kelp, oyster mushrooms (raw), pine mushrooms (raw), white mushrooms (raw), enoki mushrooms (raw), dried shiitake mushrooms, fresh shiitake mushrooms, gat kimchi (leaf mustard kimchi), radish kimchi (kkakdugi), water kimchi (nabak kimchi), dongchimi (radish water kimchi), napa cabbage kimchi, chonggak kimchi (ponytail kimchi), young radish kimchi, carrot juice |

|

Fat and oils (n = 31) |

Black sesame (dried), sesame seeds (dried), peanuts, almonds, pine nuts, seasoned cashew nuts, pistachios, sunflower seeds, walnuts, pumpkin seeds (dried), seasoned pumpkin seeds, toasted sesame seeds, peanut butter, margarine, butter, shortening, light mayonnaise, mayonnaise, Italian dressing, thousand island dressing, French dressing, perilla oil, rice bran oil, corn oil, olive oil, safflower oil, canola oil, sesame oil, soybean oil, grapeseed oil, sunflower seed oil |

|

Milk (n = 13) |

|

|

Whole milk (n = 12) |

Soy milk, lactose-free milk, regular milk, whole milk powder, milk powder, yogurt (set type), yogurt (liquid type), soft ice cream, condensed milk, strawberry milk, banana milk, chocolate milk |

|

Low-fat milk (n = 1) |

Low-fat milk |

|

Fruits (n = 52) |

Sweet persimmon, soft persimmon, dried persimmon, mandarin orange, kumquat, orange, yuzu, grapefruit, hallabong (Jeju orange), canned mandarin orange, strawberry, raspberry, fresh fig, dried fig, fresh banana, dried banana, white peach, nectarine, yellow peach, canned white peach, canned yellow peach, blueberry, canned blueberry, pineapple, canned pineapple, shine muscat, kyoho grape, raisin, apple juice, orange juice, pineapple juice, grape juice, durian, lychee, mango, plum, musk melon, pear, fuji apple, apricot, Pomegranate, watermelon, cherry, plum, Korean melon, cherry, gold kiwi, green kiwi, papaya, canned fruit cocktail, cherry tomato, tomato |

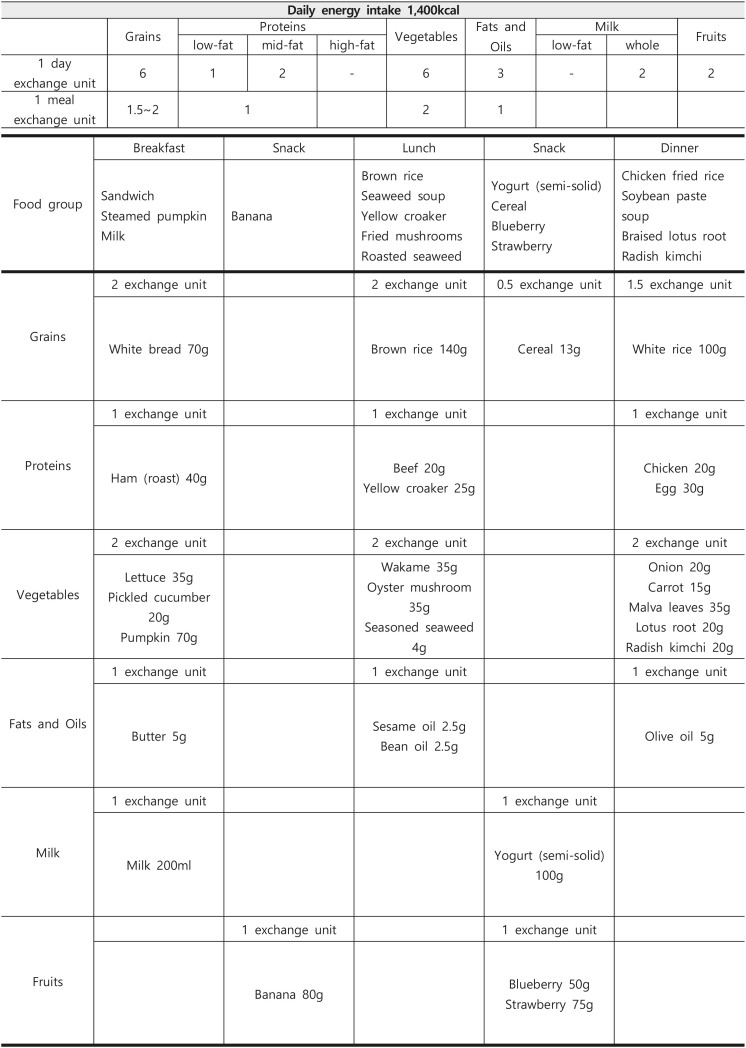

Development of educational brochure materials

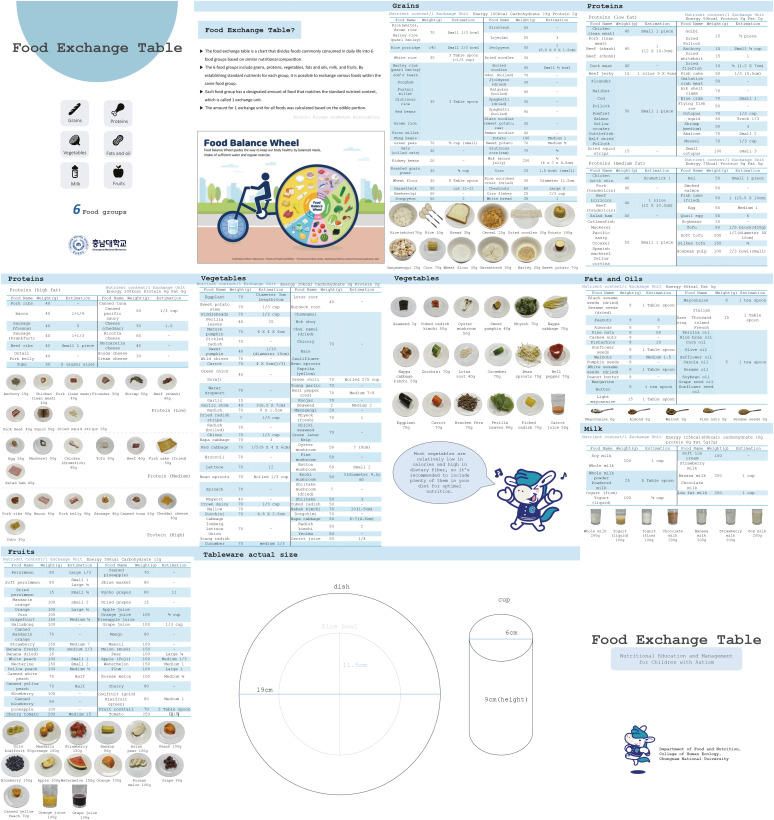

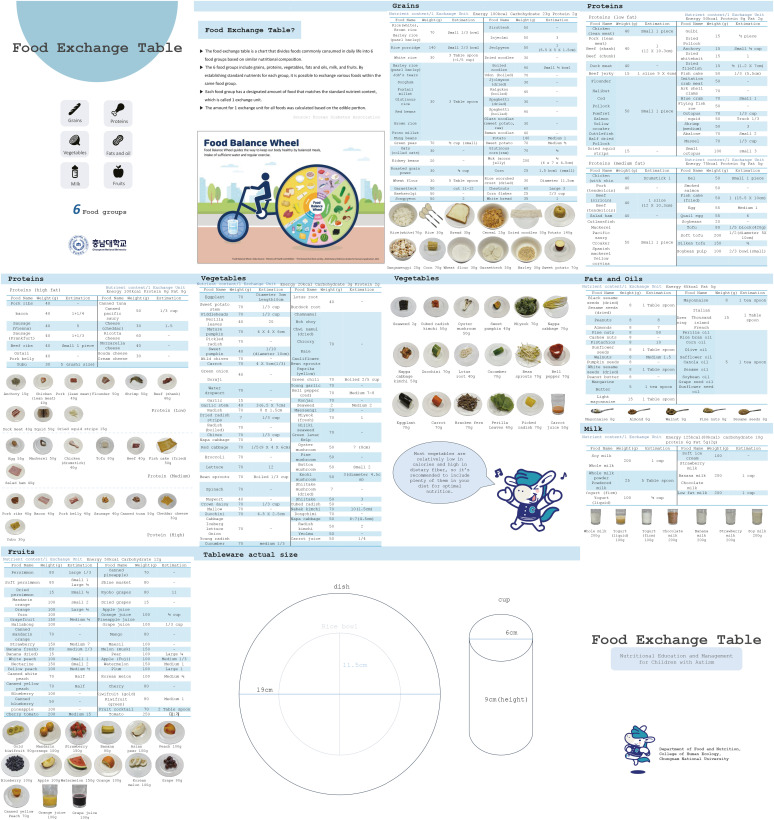

A comprehensive educational brochure was developed in B5 format, consisting of 10 pages structured to facilitate understanding of food exchange concepts and portion control. The entire brochure, including the cover page, has been added as supplementary material (

Figure 1). The front page introduces the fundamental principles of the food exchange system and features a food balance wheel diagram, emphasizing the importance of consuming a variety of foods from all six food groups to develop healthy eating habits. Pages 2 through 8 contain detailed food exchange unit tables for each food group, accompanied by representative food photographs that visually demonstrate standard exchange unit portions.

Figure 1Brochure component. The conceptual framework of a food exchange system for nutrition education for autism spectrum disorder children, a balanced diet wheel, a list of food exchanges by food group, and the actual size of the photographed utensils are organized in a 12-page brochure.

The final two pages (p. 9–10) present a practical guide for portion size estimation, featuring actual-size reference images of commonly used tableware. These reference images were carefully calibrated to the B5 scale to ensure accurate portion size estimation in real-world settings. This standardized measurement system enables users to replicate exchange unit portions accurately in their daily meal preparation.

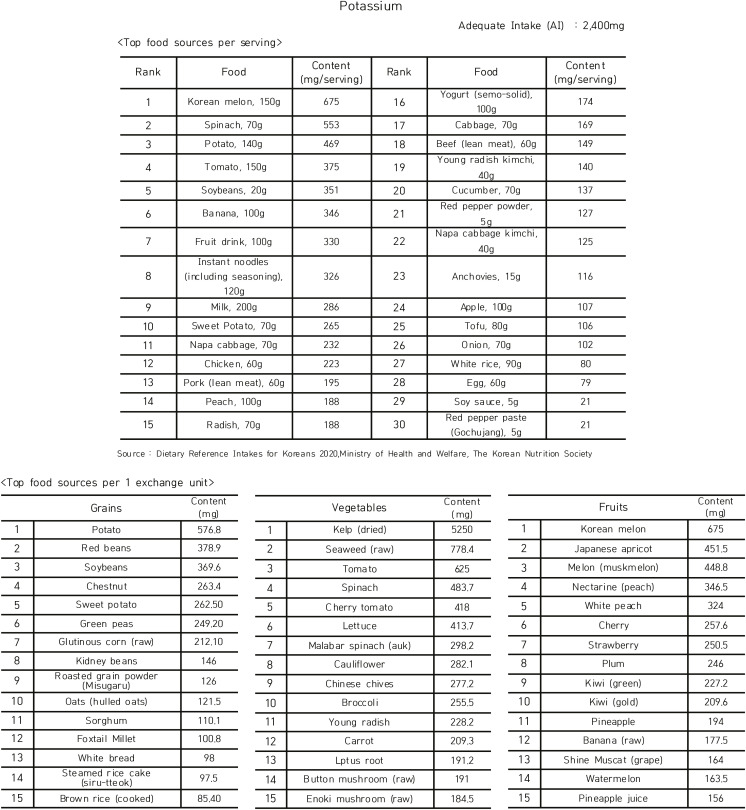

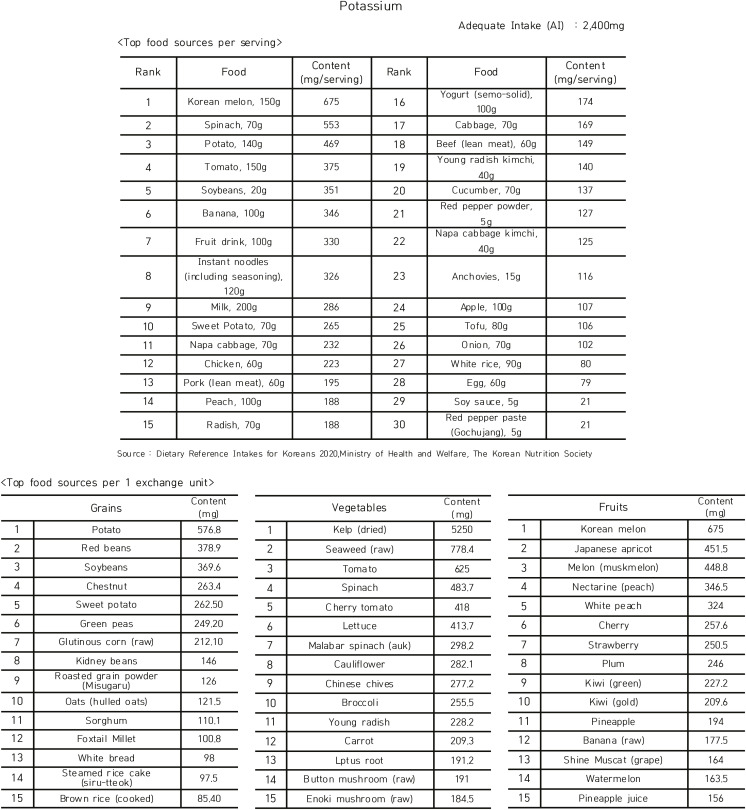

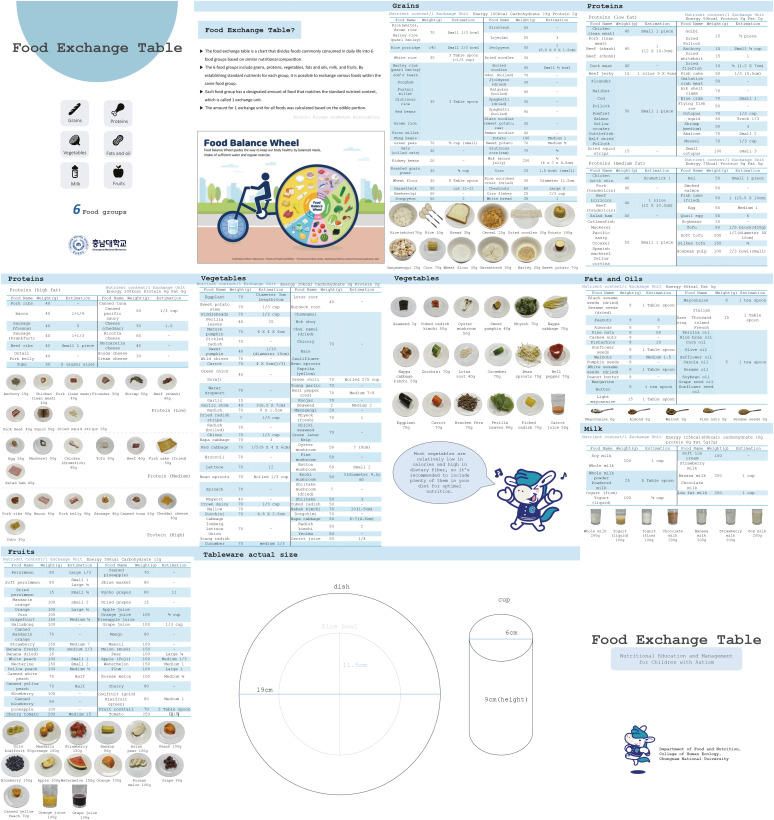

Development of nutrient source foods database

A comprehensive nutrient source food database was developed to address nutritional deficiencies commonly observed in ASD children through dietary intervention. We compiled a systematic compilation of nutrient-rich food sources, categorized by food groups and ranked according to nutrient content density. Each nutrient category includes major food sources that can effectively supplement identified deficiencies. Special consideration was given to fat and sodium, where both deficient and excessive intake patterns were observed in the target population. For these nutrients, the database includes guidelines for both supplementation and intake moderation, providing a balanced approach to nutritional management. Potassium was presented as representative nutrient (

Figure 2).

Figure 2Example of hierarchical classification of nutrient-dense foods for addressing nutritional deficiencies in children with autism spectrum disorder.

The major source foods for 19 nutrients were categorized, focusing on nutrients that are commonly deficient in ASD children, and fat and sodium were added to prevent overconsumption. Nutrients with insufficient national and international analytical data were excluded to ensure the reliability of the nutritional assessment and the nutrient-source foods were ranked after excluding foods that were not among the high-frequency and high-consumption foods for children in the age group according to the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES).

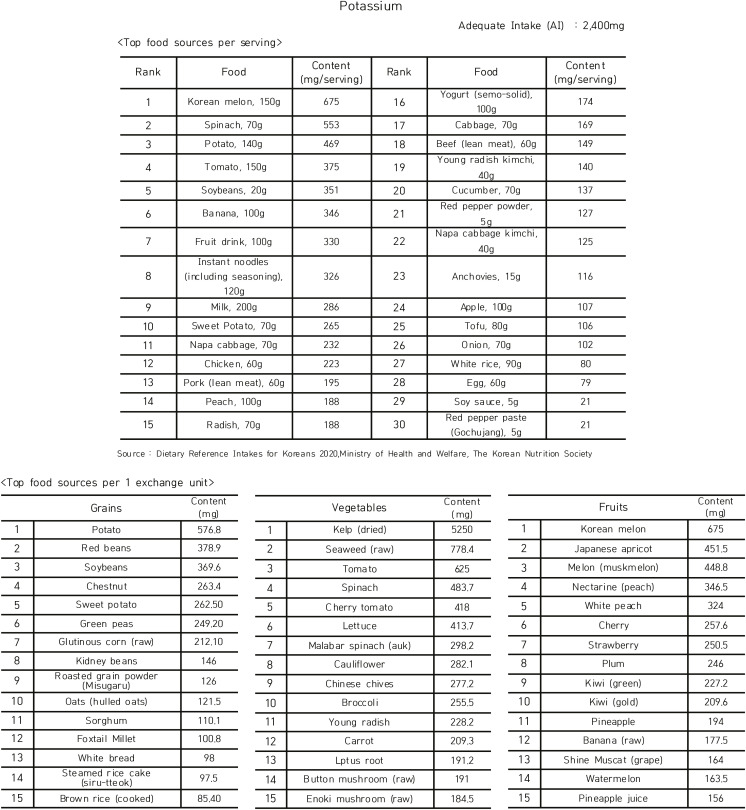

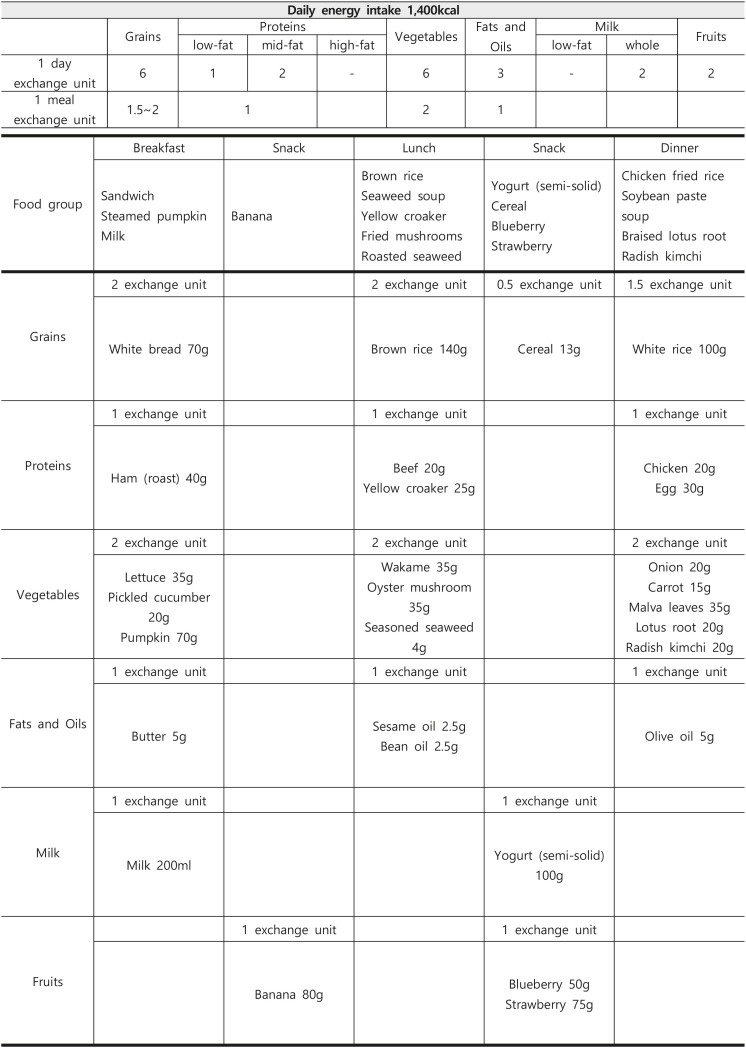

An example of a 1-day meal plan meeting the nutritional requirements of children is presented using the food exchange list. Based on the 2020 K-DRI [

19], this example was designed to provide the recommended energy intake of 1,400 kcal for children aged 3 to 5 years (

Figure 3).

Figure 3Example of a 1-day meal plan for children aged 3 to 5 years requiring 1,400 kcal.

DISCUSSION

This study developed educational brochures materials to promote proper eating habits and support healthy growth and development in ASD children. They exhibit distinct eating habits characterized by selective eating, rejections of new foods, and repetition of eating certain foods, primarily due to sensory sensitivity and limited behavioral characteristics [

6]. These eating behaviors frequently lead to nutritional imbalances that may impact their growth and development [

3,

4,

5]. Previous research has documented both eating imbalances and specific nutrient deficiencies in ASD children, while surveys of their parents have indicated high demand and willingness to participate in nutritional education programs [

11].

Various international studies have applied structured nutrition education or parent-focused behavioral intervention programs for ASD children, demonstrating their practical effectiveness and applicability.

In the United States, the

Autism Eats program was developed as a 10-week intervention with two booster sessions, targeting both children and their caregivers. The program provided personalized strategies for improving eating habits and promoting healthy dietary practices. It led to significant improvements in food variety, mealtime behaviors, and caregiver engagement [

24]. In Japan, a parent education program for caregivers of ASD children consisted of two educational sessions and discussions. The program focused on teaching strategies based on the factors influencing children’s food preferences. Through the use of visual materials, case examples, and cooperation with occupational therapists, the program significantly improved parental self-efficacy related to mealtime and increased the number of foods consumed by the children [

25]. In addition, a randomized clinical trial comparing the effectiveness of parent training and parent education for addressing behavioral problems in ASD children, while not specifically aimed at improving eating behaviors, showed that structured parent training led to a significant reduction in problem behaviors. This highlights the important role of systematic parental involvement in managing problematic behavior [

26].

These studies collectively demonstrate that structured educational approaches can be effective in improving eating behaviors and dietary adherence in ASD children, offering valuable insights for the development of intervention programs in other contexts.

First, the food exchange table originally developed for the caloric intake and planned diet of diabetic patients was revised and supplemented according to the food intake status of ASD children aged 3 to 6. Utilizing data from KNHANES and RDA, we identified and incorporated commonly consumed foods into the exchange table database. This resulted in the addition of 300 new food items across various categories, including grains (breads and cakes), low-fat proteins, vegetables, and milk. Representative foods were selected from this database and photographed to provide visual references for exchange unit portions, which were then compiled into a comprehensive brochure.

The database was further utilized to create nutrient-based food source tables, ranking items from 1st to 15th based on nutrient content within each food group. These tables served as educational tools to emphasize the importance of obtaining nutrients through dietary sources.

This research is meaningful as it developed practical nutrition education materials tailored to Korean dietary patterns and the specific needs of ASD children. In Korea, there has been a lack of structured resources suitable for ASD children, and particularly, no materials utilizing the food exchange list have been previously available. Accordingly, this study proposed approaches to help plan balanced meals and expand food choices by considering the characteristic features of ASD, such as sensory sensitivity and food selectivity. Furthermore, recognizing the crucial role of parents in managing behavioral problems in ASD children, the developed materials were designed to be practical and accessible for caregivers to implement in daily child-rearing. These materials are also expected to have valuable applications in clinical nutrition practice.

However, this study has several limitations. The primary constraint lies in the adaptation of a diabetic exchange system, which may not fully capture the unique dietary patterns of ASD children. In particular, ASD children have significantly lower intake diversity in fruit and vegetables, and the milk group compared to typically developing children [

27].

Therefore, it is necessary to review the exchange unit in consideration of the dietary group intake and nutrient requirements of ASD children. In addition, there is no exchange unit for sugary foods that ASD children frequently consume, such as jelly, candy, and chocolate. It is judged that sugar-processed products were not included for blood sugar control because the food exchange table borrowed in this study was established based on diabetic patients. This limitation poses challenges in providing practical guidance for snack consumption in real-world settings.

CONCLUSION

This research successfully developed nutritional education materials tailored for parents of ASD children. The educational package included a comprehensive brochure featuring food exchange concepts, balanced diet guidelines, and visual representations of exchange units across six food groups. Supplementary materials include nutrient source tables designed to address specific nutritional deficiencies through dietary modifications.

Given the increasing prevalence of ASD, these educational materials represent a valuable resource for implementing customized nutrition education programs aimed at promoting healthy dietary patterns and supporting optimal growth and development in ASD children.

National Research Foundation of Koreahttps://doi.org/10.13039/501100003725

2020R1A5A80176712022R1A2C1091570

NOTES

-

Funding: This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by Korean Ministry of Education (2020R1A5A8017671, 2022R1A2C1091570).

-

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

-

Author Contributions:

Conceptualization: Yoon SI, Cho JA.

Data curation: Won S, Yoon SI.

Formal analysis: Won S.

Funding acquisition: Cho JA.

Investigation: Yoon SI.

Methodology: Won S, Kim Y, Park J.

Project administration: Won S, Yoon SI.

Resources: Cho JA.

Software: Won S.

Supervision: Yoon SI.

Validation: Yoon SI.

Visualization: Yoon SI, Cho JA.

Writing - original draft: Won S, Yoon SI.

Writing - review & editing: Won S, Yoon SI, Cho JA.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cermak SA, Curtin C, Bandini LG. Food selectivity and sensory sensitivity in children with autism spectrum disorders. J Am Diet Assoc 2010;110:238-246.

- 2. Statistics Korea. Number of registered persons with disabilities by region, disability type, and gender. 2023. cited 2025 January 1. Available from https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=117&tblId=DT_11761_N005&conn_path=I2

- 3. Ahumada D, Guzmán B, Rebolledo S, Opazo K, Marileo L, et al. Eating patterns in children with autism spectrum disorder. Healthcare (Basel) 2022;10:1829.

- 4. Bandini LG, Anderson SE, Curtin C, Cermak S, Evans EW, et al. Food selectivity in children with autism spectrum disorders and typically developing children. J Pediatr 2010;157:259-264.

- 5. Min KC, Kim BK. Understanding assessment for feeding disorders in autistic spectrum disorders: a literature review. Ther Sci Rehabil 2024;13:9-25.

- 6. Vissoker RE, Latzer Y, Gal E. Eating and feeding problems and gastrointestinal dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders. Res Autism Spectr Disord 2015;12:1210-1221.

- 7. Bandini LG, Curtin C, Phillips S, Anderson SE, Maslin M, et al. Changes in food selectivity in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2017;47:439-446.

- 8. Byrska A, Błażejczyk I, Faruga A, Potaczek M, Wilczyński KM, et al. Patterns of food selectivity among children with autism spectrum disorder. J Clin Med 2023;12:5469.

- 9. Sharp WG, Berry RC, McCracken C, Nuhu NN, Marvel E, et al. Feeding problems and nutrient intake in children with autism spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis and comprehensive review of the literature. J Autism Dev Disord 2013;43:2159-2173.

- 10. Visvalingam K, Sivanesom RS. Feeding behaviors among children with autism spectrum disorder. Int J Clin Pediatr 2024;13:73-85.

- 11. Park HJ, Choi SJ, Kim Y, Park J, Kim YR, et al. Dietary behavior and food preferences according to age and the parents’ nutrition education needs of children with autism spectrum disorder. J Korean Soc Food Cult 2020;35:241-255.

- 12. Cho JW, Ju DL, Lee Y, Min BK, Kweon M, et al. Korean food exchange lists for diabetes meal planning: revised 2023. Clin Nutr Res 2024;13:227-237.

- 13. Dholvitayakhun A, Kluabwang J, eds, ddDesign of food exchange list for obesity using modified local search. 2016 13th International Conference on Electrical Engineering/Electronics, Computer, Telecommunications and Information Technology (ECTI-CON). 2016 Jun 28 - Jul 1; Chiang Mai, Thailand: Piscataway, NJ: IEEE; 2016.

- 14. Han JS, Kim JK, Jeon YS. A web-based internet program for nutritional assessment and diet prescription by renal diseases. J Korea Soc Food Sci Nutr 2002;31:847-855.

- 15. Kendall PA, Jansen GR. Educating patients with diabetes: comparison of nutrient-based and exchange group methods. J Am Diet Assoc 1990;90:238-243.

- 16. Sidahmed E, Cornellier ML, Ren J, Askew LM, Li Y, et al. Development of exchange lists for Mediterranean and Healthy Eating diets: implementation in an intervention trial. J Hum Nutr Diet 2014;27:413-425.

- 17. Alavinejad P, Hajiani E, Danyaee B, Morvaridi M. The effect of nutritional education and continuous monitoring on clinical symptoms, knowledge, and quality of life in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench 2019;12:17-24.

- 18. Kim MJ, Park CN, Kang YE, Lee SS. The effects of nutrition education and regular exercise on nutritional status, quality of life and fatigue in hemodialysis patients. J Korean Diet Assoc 2013;19:373-388.

- 19. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Dietary reference intakes for Koreans (KDRI). Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2020.

- 20. Rural Development Administration. National standard food composition table (10th revision). Jeonju: National Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Rural Development Administration; 2011.

- 21. Hubbard KL, Anderson SE, Curtin C, Must A, Bandini LG. A comparison of food refusal related to characteristics of food in children with autism spectrum disorder and typically developing children. J Acad Nutr Diet 2014;114:1981-1987.

- 22. Choi SJ, Oh JE, Kim YR, Kim Y. Mealtime behavior and food preferences of children with autism spectrum disorder and nutrition education needs perceived by special education teachers. J Korean Soc Food Cult 2021;36:40-55.

- 23. Esteban-Figuerola P, Canals J, Fernández-Cao JC, Arija Val V. Differences in food consumption and nutritional intake between children with autism spectrum disorders and typically developing children: a meta-analysis. Autism 2019;23:1079-1095.

- 24. Gray HL, Pang T, Agazzi H, Shaffer-Hudkins E, Kim E, et al. A nutrition education intervention to improve eating behaviors of children with autism spectrum disorder: study protocol for a pilot randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials 2022;119:106814.

- 25. Miyajima A, Tateyama K, Fuji S, Nakaoka K, Hirao K, et al. Development of an intervention programme for selective eating in children with autism spectrum disorder. Hong Kong J Occup Ther 2017;30:22-32.

- 26. Bearss K, Johnson C, Smith T, Lecavalier L, Swiezy N, et al. Effect of parent training vs parent education on behavioral problems in children with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015;313:1524-1533.

- 27. Park J, Kim Y, Lee S, Kim Y, Oh J, et al. A literature review of eating behaviors and nutrient intake of children with autism spectrum disorders. J Korean Assoc Pers Autism 2019;19:111-132.