ABSTRACT

Malnutrition is prevalent among older patients, leading to increased morbidity, prolonged hospitalization, and diminished quality of life. The Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) facilitates the evaluation of multifaceted health issues, enabling individualized nutritional interventions. This case report describes nutritional management guided by CGA in a 75-year-old female hospitalized for severe hypernatremia with significant malnutrition and high-risk for refeeding syndrome. Upon admission, CGA identified multiple comorbidities, cognitive impairment, and complete dependence on caregivers for daily activities. Due to persistent refusal of oral intake, enteral nutrition (EN) was cautiously initiated at 25% of the target energy requirement, with close monitoring of electrolyte levels. Despite an initial decrease in phosphorus levels suggestive of refeeding syndrome, gradual advancement of nutritional support successfully stabilized her clinical condition. Following discharge, structured caregiver education was provided to support EN at home; however, suboptimal intake persisted due to gastrointestinal intolerance, resulting in weight loss. Post-discharge follow-ups identified feeding rate-related symptoms, necessitating formula adjustments and caregiver re-education. This case emphasizes the critical role of CGA in early malnutrition detection, individualized nutritional intervention, prevention of refeeding syndrome, and the importance of continuous post-discharge monitoring and caregiver education. Although the findings are limited by the single-case design, proactive CGA-based nutritional interventions remain crucial for optimizing clinical outcomes in older patients hospitalized due to acute medical problems. Further research involving larger samples and prolonged follow-up periods is required to validate the long-term benefits of CGA-based nutritional intervention.

-

Keywords: Aged, Nutrition therapy; Geriatric assessment

INTRODUCTION

The older population in South Korea has been rapidly increasing, exceeding 20% of the total population as of December 2024 [

1], and it is projected to exceed 30% by 2036 and 40% by 2050 [

2]. Older patients frequently present with multiple chronic diseases. Due to their degenerative nature, they are challenging to cure and are associated with an increased risk of complications. Furthermore, issues such as the adverse effects of polypharmacy, cognitive decline, and a reduced ability to perform daily activities further contribute to malnutrition. Malnutrition is a critical factor leading to increased mortality and morbidity in older patients and is closely linked to prolonged hospitalization, a higher incidence of infections and complications, and a decline in physical function, ultimately diminishing their overall quality of life [

3]. Consequently, proper assessment and early intervention in the nutritional status of older patients within medical settings are essential.

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) is a multidisciplinary process that evaluates the medical, functional, psychological, and social aspects of older adults through a multidimensional approach. Its primary goals are to detect reversible problems early and to establish a coordinated, individualized care plan. CGA has been shown to improve functional status, reduce institutionalization, and increase survival rates. Consequently, CGA has become a key tool for evidence-based, personalized care in geriatric medicine [

4]. Recent studies support the use of CGA in identifying malnutrition and informing targeted nutrition interventions. A real-world cross-sectional study by Ju et al. demonstrated that CGA parameters—including activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental ADL (IADL), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), body mass index (BMI), Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), mid-arm circumference (MAC), and calf circumference (CC)—were significantly associated with nutritional status in older adults. Notably, higher GDS scores and lower BMI, MAC, and CC were strongly linked to undernutrition, suggesting that CGA can serve as an effective tool for early risk detection and stratification [

5]. Similarly, a cross-sectional survey conducted among the healthcare professionals in Japan showed that those incorporating CGA into clinical practice were significantly more likely to assess for sarcopenia, sarcopenic dysphagia, and cachexia, and to define individualized nutritional goals, compared to those who did not use CGA. These findings highlight the utility of CGA as a foundation for proactive and personalized nutrition management in geriatric care [

6].

This case report describes the implementation of CGA-based nutritional support in an older patient hospitalized due to an acute medical problem and highlights the importance of timely and individualized nutritional intervention in this population.

This case report was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (IRB No. B-2503-960-701). This study was conducted with the patient's written informed consent.

CASE

A 75-year-old female patient was admitted with hypernatremia (serum sodium level: 175 mEq/L on November 26, 2024) as the chief complaint, with a total hospitalization period of 14 days (November 26–December 9, 2024). During her hospitalization, she was referred to the Nutrition Support Team (NST) twice and underwent two follow-up consultations at one-month intervals post-discharge.

The results of the patient’s CGA, conducted at the time of admission (November 26), are presented in

Table 1. The CGA revealed multiple underlying conditions, including diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and dementia, as well as a history of hospitalizations due to hypernatremia in September and November 2021. The patient was entirely dependent on caregivers for ADL and IADL, as assessed by a qualified nurse, and was in a bedridden status, making the assessment of physical function unfeasible. A nutrition assessment conducted by a clinical dietitian indicated that the patient had been receiving oral nutrition with caregiver assistance; however, her oral intake had progressively declined over the preceding 3–4 weeks. One week prior to admission, she had nearly ceased oral intake, refusing to open her mouth. Additionally, the patient refused to take the prescribed medications. Although her weight changes prior to admission were unknown, the patient’s height, weight, and BMI on admission were 150 cm, 39.5 kg, and 17.6 kg/m

2, respectively, classifying her as underweight. Furthermore, her CC was measured at 24.0 cm, suggesting muscle mass depletion. The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) score was 7, classifying the patient as malnourished. The medication assessment conducted by a pharmacist confirmed that hypernatremia was not drug-related. Rather, it was diagnosed as a result of exacerbated dehydration due to prolonged insufficient fluid intake and reduced oral nutritional intake.

Table 1 Summary of comprehensive geriatric assessment

Table 1

|

Category |

Content of assessment |

Assessment results |

|

1. Demographic information |

1) Caregiver |

Spouse, adult child |

|

2) Decision maker |

Spouse, adult child |

|

2. Medical evaluation |

1) Problem list |

Underlying disease: diabetes, dyslipidemia, Alzheimer's disease, h/o hypernatremia (21. Sep, Nov) |

|

Current problem: hypernatremia d/t poor oral intake, dehydration |

|

2) Medication assessment |

Medication list: |

|

- Rosuzet 10/5 mg tab (ezetimibe/rosuvastatin) 1 tab qd pc |

|

- Trajenta 5 mg tab (linagliptin) 0.5 tab qd pc |

|

Adherence: with caregiver assistance, the patient was able to take oral medication, demonstrating good medication adherence. However, in the days leading up to hospitalization, she had minimal oral intake and was unable to take her medication for 1–2 days before admission. |

|

3. Physical function assessment |

1) Timed get up & go test |

Not measurable |

|

2) Gait speed |

Not measurable |

|

3) Grip strength |

Not measurable |

|

4) ADL |

0 |

|

5) IADL |

0 |

|

4. Mental status assessment (including cognitive and depressive symptoms) |

1) K-MMSE-2 |

0 |

|

2) SGDS-K |

Not measurable |

|

5. Nutrition assessment |

1) BMI |

17.6 kg/m2

|

|

2) Mid-arm circumference |

22.0 cm |

|

3) Calf circumference |

24.0 cm |

|

4) MNA |

7 points/30 points |

|

5) Comment |

The patient typically consumed two meals per day, each consisting of approximately two-thirds of a bowl of rice, one or two exchange units of fish or meat side dishes, and two exchange units of vegetable side dishes. Approximately 3 to 4 weeks ago, the patient’s oral intake began to decline. Over the past week, she has been in a near NPO state, either holding food in her mouth without swallowing or refusing to open her mouth. Although recent weight changes are unknown, muscle wasting has been observed, and her current nutrition status is assessed as moderate malnutrition. |

On November 27, the patient was referred to the NST for the planning and initiation of enteral nutrition (EN). The patient’s caregiver expressed a negative perception of tube feeding; however, it was explained that continued refusal of oral intake could lead to recurrent malnutrition and electrolyte imbalances. Consequently, based on the medical team’s clinical judgment and with the caregiver’s consent, EN was initiated via a nasogastric tube. In determining the EN regimen, the patient’s existing oral intake, ADL and IADL assessment results, bedridden status precluding physical function assessment, and older age (75 years) were considered. The target energy requirement was estimated by multiplying Basal Energy Expenditure by a physical activity level of 1.2, resulting in a total of 1,100 kcal/day. Additionally, the 2022 European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) guidelines recommend a minimum protein intake of 1 g/kg/day for older patients, with a suggested range of 1.2–1.5 g/kg/day for individuals with acute or chronic conditions [

7]. Based on these guidelines, and considering the patient's underlying chronic conditions (diabetes mellitus and dementia), low BMI, and decreased CC, protein requirements were calculated based on the current body weight with a coefficient of 1.2. This calculation resulted in an estimated requirement of 50 g/day. A standard EN formula was selected, taking into account that fiber-containing formulas have been reported to support normal gastrointestinal (GI) function.

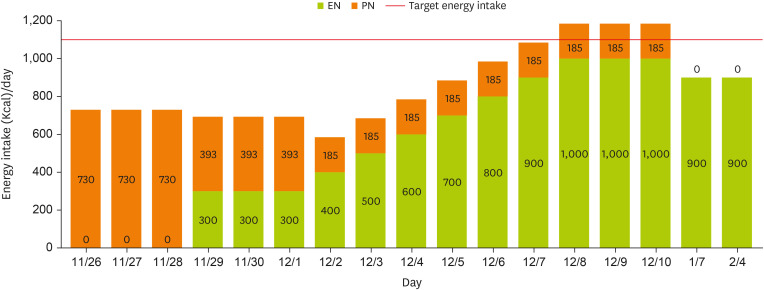

Notably, the patient had experienced inadequate nutritional intake for more than two weeks (with near-total nil per os status for over three weeks) and presented with a low BMI, classifying her as at high-risk for refeeding syndrome. Accordingly, the initial EN provision was recommended to begin at 25% of the target energy requirement, set at 300 kcal/day. However, as parenteral nutrition (PN) had been initiated on November 26, providing approximately 66% of the target energy requirement, a decline in phosphorus levels was observed (

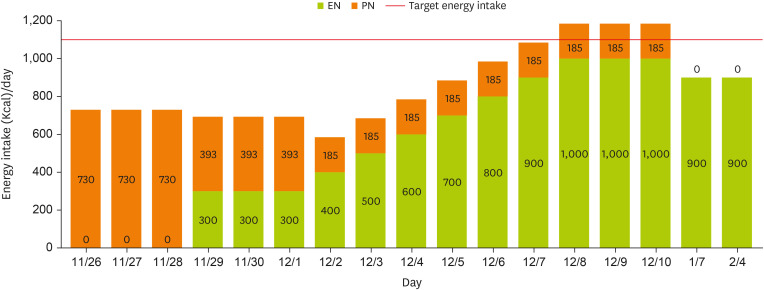

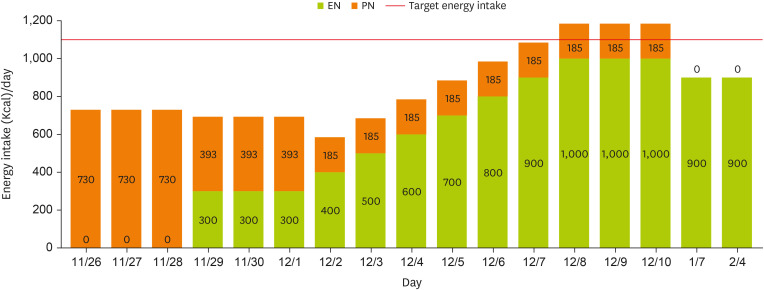

Table 2). Following the initiation of EN on November 29, phosphorus levels dropped rapidly, raising concerns regarding refeeding syndrome. To prevent refeeding syndrome, continuous monitoring was conducted. Initially, EN provision was maintained at 25% of the target energy requirement for at least three days, sustaining 300 kcal/day. Simultaneously, TPN formulation was entirely replaced with an intravenous lipid emulsion, reducing total energy supply to less than 50% of the initial supply. By December 3, phosphorus levels had normalized, and no further signs indicative of refeeding syndrome were observed. According to the guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and the Clinical Nutrition Steering Group, patients at risk for refeeding syndrome should have their nutritional intake gradually increased over 4–7 days until the target energy requirement is achieved. In accordance with these recommendations, energy intake was increased by 100 kcal per day beginning on December 3, with PN administered concurrently, achieving the target intake of 1,100 kcal/day by December 7 (

Figure 1). Throughout hospitalization, EN was well tolerated without GI complications. As EN stabilized, the patient’s BMI increased from 17.6 kg/m

2 to 18.7 kg/m

2. Additionally, blood sodium, aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine levels improved, reflecting an overall enhancement in her clinical condition.

Table 2 Anthropometric & biochemical data

Table 2

|

Parameter |

Normal range |

|

Hospitalization period |

|

Post discharge 2 mon |

|

Nov 26, 2024 |

Nov 27, 2024 |

Nov 28, 2024 |

Nov 29, 2024 |

Nov 30, 2024 |

Dec 1, 2024 |

Dec 2, 2024 |

Dec 3, 2024 |

Dec 4, 2024 |

Dec 5, 2024 |

Dec 6, 2024 |

Dec 9, 2024 |

Feb 4, 2025 |

|

Height (cm) |

- |

150.0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Weight (kg) |

41.6–51.7 |

- |

39.5 |

40.2 |

40.1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

42.7 |

42.5 |

- |

42.0 |

40.5 |

|

BMI (kg/m2) |

18.5–23.0 |

- |

17.6 |

17.9 |

17.8 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

19.0 |

18.9 |

- |

18.7 |

- |

|

Albumin (g/dL) |

3.3–5.2 |

4.0 |

3.2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2.5 |

2.6 |

2.4 |

2.3 |

2.4 |

2.8 |

3.0 |

|

Na (mg/dL) |

135–145 |

175 |

165 |

156 |

146 |

148 |

141 |

138 |

140 |

139 |

- |

- |

135 |

138 |

|

K (mg/dL) |

3.5–5.5 |

4.1 |

4.7 |

3.7 |

3.2 |

3.3 |

3.4 |

3.4 |

3.5 |

3.7 |

- |

- |

4.6 |

4.9 |

|

Ca (mg/dL) |

8.8–10.5 |

9.4 |

8.7 |

8.6 |

8.3 |

7.7 |

7.5 |

7.7 |

8.0 |

7.6 |

- |

- |

8.5 |

- |

|

P (mg/dL) |

2.5–4.5 |

5.3 |

3.5 |

2.8 |

2.6 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

1.7 |

3.2 |

3.2 |

- |

- |

4.2 |

- |

|

AST (IU/L) |

0–40 |

66 |

27 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

44 |

54 |

74 |

88 |

79 |

39 |

40 |

|

ALT (IU/L) |

0–40 |

114 |

66 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

60 |

61 |

60 |

65 |

68 |

51 |

50 |

|

BUN (mg/dL) |

10–26 |

61 |

58 |

49 |

33 |

20 |

12 |

8 |

9 |

11 |

- |

- |

18.0 |

21.6 |

|

Cr (mg/dL) |

0.7–1.4 |

1.4 |

1.0 |

0.8 |

0.6 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

- |

- |

0.3 |

0.45 |

|

eGFR (CKD-EPI) |

- |

35.8 |

52.7 |

69.2 |

89.0 |

- |

- |

95.0 |

103.1 |

104.0 |

- |

- |

112.4 |

- |

|

CRP |

0–0.5 |

0.6 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3.0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.3 |

0.06 |

Figure 1

Changes in energy intake through EN and PN.

EN, enteral nutrition; PN, parenteral nutrition.

Accordingly, a discharge plan for home care was established on December 7, including a structured caregiver education program on the continuation of EN post-discharge. The caregiver received instruction on daily target energy requirements, EN formulas, administration techniques, and the management of potential GI complications, to ensure the safe continuation of EN at home. However, post-discharge monitoring was deemed necessary, as the patient was discharged without fully achieving the target energy intake, and the primary caregiver lacked proficiency in EN administration. Furthermore, a qualified nurse determined that continued home nursing care was essential to ensure safe and effective long-term nutritional management, considering the caregiver’s older age and limited ability to manage the patient’s care.

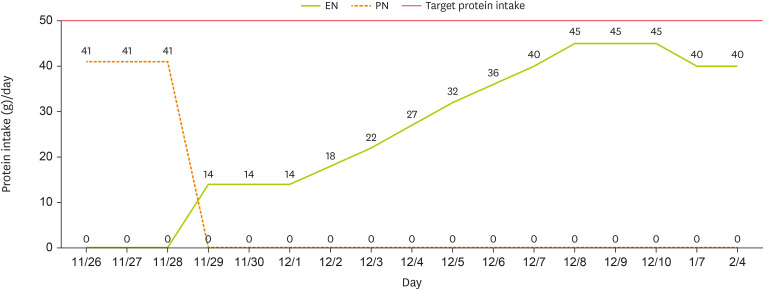

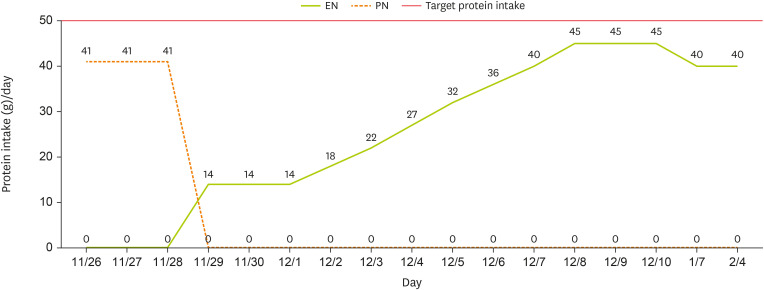

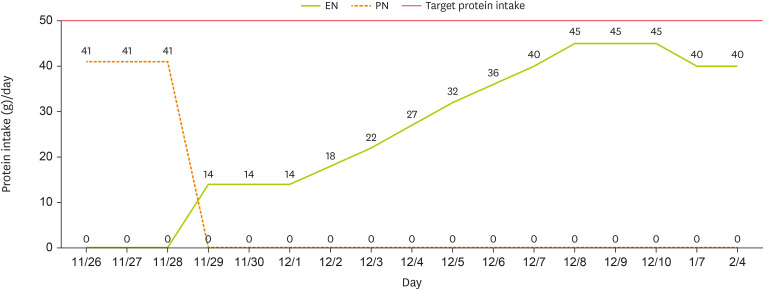

At the one-month follow-up after discharge, the caregiver reported that EN had been increased from 1,000 kcal/day to 1,100 kcal/day. However, due to an increased frequency of defecation and the occurrence of diarrhea, the intake was subsequently reduced to 900 kcal/day, approximately 80% of the target energy and protein requirement (

Figures 1 and

2). A review of the patient’s medications revealed no drugs associated with diarrhea, but it was noted that the enteral feeding infusion rate had increased to 300–400 mL/hr. It was determined that the GI complications were likely attributable to this change in infusion rate, prompting additional caregiver education on appropriate rate adjustments. At the two-month follow-up after discharge, blood test results from an external facility and EN were assessed. Laboratory findings indicated an overall stable condition. After the infusion rate was adjusted based on recommendations from the first follow-up, the caregiver attempted to increase EN to meet the target energy requirement. However, intermittent diarrhea persisted and prevented the patient from achieving the desired intake level, and the caregiver administered 900 kcal/day. Additionally, a weight loss of 1.5 kg over two months was observed compared to discharge. Consequently, a low-fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols formula, designed to minimize the intake of fermentable polysaccharides and other potential diarrhea-inducing components, was recommended. Furthermore, the caregiver received re-education on gradually increasing caloric intake in small increments. However, due to concerns regarding potential micronutrient deficiencies associated with prolonged low-calorie intake, regular blood tests and ongoing nutrition counseling were discussed with the medical team to ensure comprehensive monitoring and management.

Figure 2

Changes in protein intake through EN and PN.

EN, enteral nutrition; PN, parenteral nutrition.

DISCUSSION

Older patients are at an increased risk of malnutrition due to a complex interplay of age-related factors, including chronic diseases, polypharmacy, and changes in nutritional status. Malnutrition often results in weight loss, muscle mass depletion, impaired immune function, and delayed wound healing, all of which contribute to functional decline and reduced survival rates [

3]. Previous studies have consistently demonstrated that nutritional support, particularly when guided by clinical dietitians, can lead to better clinical outcomes in patients at high-risk of malnutrition. These interventions have been associated with a significant reduction in mortality and complication rates [

8], as well as improvements in body weight, MNA scores, and reductions in both average hospital stay and six-month readmission rates [

9]. These findings highlight the importance of proactive nutritional care in supporting patient recovery and overall health.

Several studies have emphasized the importance of CGA in evaluating the nutritional status of older patients and supporting long-term health management. As a multidimensional tool, CGA assesses physical, psychological, and social functioning, enabling a comprehensive understanding of the patient’s overall health and informing the development of tailored treatment plans [

3,

4,

5,

6]. By incorporating assessments such as ADL and the Korea-MMSE-2nd edition, CGA helps identify signs of nutritional imbalance, such as muscle mass depletion, while also evaluating the patient’s ability to perform self-care. Social evaluations further help determine the need for external support, ensuring a more holistic approach to individualized care. In the present case, CGA enabled a thorough assessment of the patient’s medication use, physical function decline, and cognitive impairment. In this case, the CGA enabled the development of an individualized nutrition therapy plan and facilitated early identification of refeeding syndrome risk upon admission, allowing for timely implementation of a gradual nutrition support plan tailored to the patient’s needs.

Refeeding syndrome is a metabolic disorder that can occur when nutrition is rapidly reintroduced following severe malnutrition, with symptoms ranging from mild electrolyte imbalances to life-threatening complications. Older patients are particularly vulnerable due to chronic disease, sarcopenia, and inadequate dietary intake. According to the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition Consensus Criteria, refeeding syndrome risk is classified as moderate or significant based on indicators such as BMI, weight loss, caloric intake, and electrolyte imbalances. Patients with significant weight loss, prolonged fasting, or severe electrolyte disturbances are considered high-risk [

10]. Given that refeeding syndrome occurs in approximately 19% of hospitalized older patients, early risk assessment at admission is essential. This includes evaluating BMI, recent weight loss, and electrolyte levels while carefully adjusting nutrition delivery rates and proactively correcting electrolyte imbalances to prevent complications [

11]. In this case, severe malnutrition was identified during the initial CGA, and a decline in serum phosphorus levels was observed following the initiation of nutrition support. Consequently, close monitoring was conducted to prevent excessive initial nutrient provision. With stable EN support, positive clinical outcomes, including weight gain and the correction of electrolyte imbalances, were observed throughout the hospitalization.

Furthermore, this case underscores the importance of continued nutritional intervention following hospital discharge. The 2022 ESPEN guidelines emphasize the vital role of caregiver education in supporting the nutritional management of older patients [

7]. In line with this, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated that post-discharge nutritional support significantly improves long-term survival and increases both energy and protein intake in malnourished individuals [

12]. Additionally, a randomized controlled trial reported that individualized, home-based nutritional counseling substantially reduced 30- and 90-day readmission rates among older adults living alone [

13]. In this case, the caregiver received EN education prior to discharge, and additional post-discharge counseling addressed adjustments to the infusion rate based on stool consistency, as well as appropriate modifications to EN formulas. Despite two follow-ups, the patient’s target energy intake was not achieved. Most standard EN formulas provide an adequate supply of vitamins and minerals to meet the Dietary Reference Intake when administered at a daily volume of 1,000–1,500 mL [

14]. However, aging is generally accompanied by a decline in resting energy expenditure, and reduced physical activity further lowers overall energy requirements [

8]. Additionally, age-related decreases in gastric acid secretion and delayed gastric emptying can increase the risk of GI complications. Consequently, prolonged suboptimal nutrient intake can lead to micronutrient deficiencies, which may impair immune function, exacerbate sarcopenia, and contribute to cognitive decline [

15]. Therefore, periodic monitoring of blood micronutrient levels after discharge, along with collaboration with healthcare professionals to develop appropriate supplementation strategies—whether via oral supplementation or intravenous administration—is essential. Ongoing nutrition intervention is critical to ensure continued home EN and long-term nutritional stability in older patients.

This case illustrates that multidisciplinary nutrition interventions guided by CGA may improve clinical outcomes when maintained during hospitalization and post-discharge. However, implementing such interventions remains limited in Korea due to structural and systemic barriers.

Currently, the national health insurance system does not provide reimbursement for outpatient or post-discharge nutrition counseling for older adults, thereby disrupting continuity of nutritional care following hospital discharge. This discontinuity may contribute to deterioration in nutritional status, including weight loss, micronutrient deficiencies, increased risk of re-hospitalization, and functional decline. Effective nutrition care for older adults requires ongoing collaboration among multiple healthcare professionals. However, integrated care systems that connect acute care hospitals with community-based services are lacking. Many older adults live alone or with older caregivers, placing the burden of nutritional care on families who may lack the resources or knowledge to manage it effectively. These challenges can undermine the long-term effectiveness of nutrition interventions. Policy changes are needed to address these barriers. First, reimbursement for outpatient and transitional nutrition services is essential to support the continued involvement of clinical dietitians. Second, stronger linkages between hospital and community services—such as public health centers, home health nursing, and senior service programs—are required to ensure continuity of care. Third, expanding caregiver training programs can improve in-home nutrition support.

Clinical dietitians play a key role in post-discharge nutritional management, including caregiver education, dietary intake monitoring, and disease-specific dietary planning. Supporting their sustained involvement through healthcare policy and infrastructure is essential for delivering effective, long-term nutrition interventions. These measures are vital not only for maintaining the health and function of older adults but also for reducing unnecessary healthcare utilization.

This report describes a single case without long-term follow-up; therefore, the generalizability of the findings is limited, and future research with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up is necessary to confirm these results. Nevertheless, this case highlights the critical importance of timely, CGA-guided nutritional intervention in older patients hospitalized for acute medical conditions.

NOTES

-

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

-

Author Contributions:

Conceptualization: Park D, Shin AR, Park Y.

Data curation: Park D.

Investigation: Park D, Shin AR.

Supervision: Park Y.

Visualization: Park D.

Writing - original draft: Park D.

Writing - review & editing: Shin AR, Park Y.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ministry of the Interior and Safety. Population aged 65 and over reaches 20%. 2024. cited 2025 February 14. Available from https://www.mois.go.kr

- 2. Statistics Korea. 2024 Older adult statistics. 2024. cited 2025 February 14. Available from https://kostat.go.kr

- 3. Tomasiewicz A, Polański J, Tański W. Advancing the understanding of malnutrition in the elderly population: current insights and future directions. Nutrients 2024;16:2502.

- 4. Choi JY, Rajaguru V, Shin J, Kim KI. Comprehensive geriatric assessment and multidisciplinary team interventions for hospitalized older adults: a scoping review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2023;104:104831.

- 5. Ju Y, Lin X, Zhang K, Yang D, Cao M, et al. The role of comprehensive geriatric assessment in the identification of different nutritional status in geriatric patients: a real-world, cross-sectional study. Front Nutr 2024;10:1166361.

- 6. Ueshima J, Maeda K, Wakabayashi H, Nishioka S, Nakahara S, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment and nutrition-related assessment: a cross-sectional survey for health professionals. Geriatrics (Basel) 2019;4:23.

- 7. Volkert D, Beck AM, Cederholm T, Cruz-Jentoft A, Hooper L, et al. ESPEN practical guideline: clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clin Nutr 2022;41:958-989.

- 8. Schuetz P, Fehr R, Baechli V, Geiser M, Deiss M, et al. Individualised nutritional support in medical inpatients at nutritional risk: a randomised clinical trial. Lancet 2019;393:2312-2321.

- 9. Hiramatsu M, Momoki C, Oide Y, Kaneishi C, Yasui Y, et al. Association between risk factors and intensive nutrition intervention outcomes in elderly individuals. J Clin Med Res 2019;11:472-479.

- 10. da Silva JSV, Seres DS, Sabino K, Adams SC, Berdahl GJ, et al. ASPEN consensus recommendations for refeeding syndrome. Nutr Clin Pract 2020;35:178-195.

- 11. Terlisten K, Wirth R, Daubert D, Pourhassan M. Refeeding syndrome in older hospitalized patients: incidence, management, and outcomes. Nutrients 2023;15:4084.

- 12. Kaegi-Braun N, Kilchoer F, Dragusha S, Gressies C, Faessli M, et al. Nutritional support after hospital discharge improves long-term mortality in malnourished adult medical patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr 2022;41:2431-2441.

- 13. Lindegaard Pedersen J, Pedersen PU, Damsgaard EM. Nutritional follow-up after discharge prevents readmission to hospital - a randomized clinical trial. J Nutr Health Aging 2017;21:75-82.

- 14. Limketkai BN, Hurt RT, Palmer LB. The ASPEN adult nutrition support core curriculum. 3rd ed. Silver Spring: American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN); 2017.

- 15. O’Connor D, Molloy AM, Laird E, Kenny RA, O’Halloran AM. Sustaining an ageing population: the role of micronutrients in frailty and cognitive impairment. Proc Nutr Soc 2023;82:315-328.