ABSTRACT

Nutrition fact labels (NFLs) are a simple way to help people improve their nutritional intake by making healthier food choices. This study aimed to evaluate NFL use and eating habit changes among quarantined and hospitalized coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients during the pandemic. This cross-sectional study used data from the 2019 and 2020 Korean Community Health Surveys (KCHSs). Data were collected from 229,099 subjects in 2019 and 229,269 subjects in 2020. In the 2020 KCHS, data from 1,073 COVID-19 patients were included. NFL use was divided into 4 categories based on a questionnaire: affect, read, aware, and never heard. Among COVID-19 patients, 32.15% reported that they had not heard of NFLs (never heard group) compared to 44.36% of the healthy population (p < 0.001). A total of 35.1% of COVID-19 patients who reported daily life change scores of 20 or less were in the affect group compared to 23.8% of healthy subjects. In the affect group, the proportion of respondents who reported increased consumption of delivered food was 38.7% in the COVID-19 group, which was 17.1% higher than that in the never heard group (Cramér’s V = 0.257; p < 0.001). Respondents with increased consumption of fast food/soda showed a higher ratio of having never heard of NFLs among healthy subjects (28.5%) than among COVID-19 patients (22.5%; p = 0.043). Confirmed COVID-19 infections and more unfavorable daily life changes due to COVID-19 led to increased nutritional information seeking and NFL use.

-

Keywords: Pandemic; Nutritional assessment; Eating habits; Food preferences; Inpatients

INTRODUCTION

The first coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patient in Korea was diagnosed on January 20, 2020, and subsequently, a large-scale epidemic began in Korea. COVID-19 caused ‘pandemic fear,’ such as panic attacks, anxiety, fear, depression, and stress, which are known to have implications for low-quality nutritional intake [

1]. During the pandemic, as people experienced unfavorable daily routines that were harmful to health, public interest in nutrition quality through proper food selection increased [

2]. Changes, such as the consumption of high-energy (carbohydrates and lipids) foods to cope with stress and buying food for long-term storage, including canned foods, frozen foods and prepared foods, became highly dependent on accessibility . Moreover, the prolonged pandemic brought about positive changes among people, such as ‘attention to nutrition and immunity-related knowledge in the COVID-19 epidemic period, belief that improving nutrition can prevent COVID-19, and willingness to accept advice on how to improve their diet’ [

3]. However, no food or healthy functional food has been proven to be able to prevent viral diseases such as COVID-19 . It is important for all people to have access to correct nutritional information to make better food choices [

4].

Nutrition fact labels (NFLs), also referred to as nutrition information panels, are labels found on packaged and manufactured food products that display nutrient and ingredient contents [

5]. During the pandemic, particularly in isolation and non-face-to-face social settings, NFLs were almost the sole accessible source of nutritional information. Therefore, it is essential to investigate changes in NFL usage regarding nutritional information seeking behaviors based on COVID-19 diagnosis and lifestyle alterations during the pandemic.

However, previous studies have primarily focused on a limited number of lifestyle changes within specific populations or genders during the COVID-19 period. Therefore, we aim to utilize nationwide data to explore changes in eating habits and the extent of NFL utilization among both confirmed COVID-19 patients and healthy individuals. This rigorous cross-sectional study included 1,073 quarantined/hospitalized COVID-19 patients in 2020 and more than 200,000 healthy subjects in 2019 and 2020. This study aimed to analyze interest in NFLs as a nutritional information-seeking method in a pandemic situation by comparing the use of NFLs before and after the COVID-19 outbreak in all populations and among COVID-19 patients and healthy subjects during the pandemic. Furthermore, differences in the use of NFLs according to changed eating habits and changes in daily life among COVID-19 patients and healthy subjects were analyzed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data collection and study subjects

This study employed a cross-sectional design utilizing data from the 2019 and 2020 Korean Community Health Surveys (KCHSs). The KCHS is a comprehensive, region-based national survey conducted annually since 2007, designed to assess community health conditions across Korea. It is mandated by Article 4 of the Local Health Act and further detailed in Article 2 of the Enforcement Decree of the same Act. The KCHSs for 2019 and 2020 were conducted over a period from August 16th to October 31st each year. Following data collection, the raw data were made publicly available in the third quarter of the subsequent year. The survey encompassed all 17 cities and provinces in South Korea, involving participation from 255 public health centers with a target of 900 respondents per center, and collaboration with 34 representative universities to ensure wide coverage and representation. In 2019, the survey successfully gathered data from 229,099 subjects. The 2020 survey, conducted amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, collected data from 229,269 subjects. This year’s data set is particularly significant as it reflects the impact of COVID-19, with the first case reported in December 2019 and the implementation of social distancing policies starting in March 2020. Notably, the 2020 KCHS dataset includes information from 1,073 individuals who were either quarantined or hospitalized due to COVID-19, providing crucial insights into the pandemic’s effects on community health. The methodology employed ensured a robust and comprehensive data set, capturing a wide array of health-related variables, which are crucial for analyzing changes in health behaviors and conditions before and during the pandemic.

Ethical review

Written informed consent was obtained before KCHS participation, and this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) (2016-10-01-T-A) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All data analyses were conducted in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of the KCDC.

Socioeconomic and anthropometric data

The overall data profiles include critical aspects such as household selection, participant selection, sample size, data weighting, standardization, and the specifics of survey contents and methods. These have been thoroughly documented in previous studies by Kang et al. [

6] and Kim et al. [

7]. Data collection was carried out using a computer-assisted personal interview approach. This involved trained researchers visiting selected households to conduct electronic surveys using a laptop, ensuring data accuracy and consistency. The survey gathered extensive socioeconomic information, including details on the region, household income, education level, occupation, and safety awareness level, providing a comprehensive socioeconomic profile of the participants. In addition to socioeconomic data, the survey collected information on physical activity levels, which is critical for understanding health behaviors. Anthropometric measurements, including weight, height, and the calculated body mass index (BMI) [

8], were also obtained. These measurements are essential for assessing the physical health status of the participants. Data on obesity were collected as well, following the guidelines established in previous research [

9]. This detailed methodological approach ensures that the data are both reliable and valid, enabling an in-depth analysis of the health and socioeconomic factors impacting the study population. By employing a standardized data collection method, the study maintains a high level of data integrity, allowing for robust conclusions to be drawn from the findings.

Globally and in Korea, for people of all ages, NFLs provide easy-to-access nutrition information and are an effective and powerful health promotion tool to help people make healthy food choices. According to previous studies, patients who ate diets lower in fat, as well as patients who ate diets higher in fruits, vegetables, and fiber, were much more likely to use NFLs to guide their food purchase decisions than patients whose diets were higher in fat (51% vs. 26%). Therefore, the level of NFL utilization is directly related to high-quality food intake and nutritional status [

10]. Previous studies on NFLs had certain limitations; some studies were not conducted during pandemic situations, there was no separation between ill patients and the healthy public [

11], and they included only one sex or certain age groups [

12].

NFLs were first developed and introduced in the United States in 1994, when Korea also made NFLs mandatory for special-purpose foods and supplement products [

13]. In Korea, NFLs are regulated by the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety and implemented for foods such as retort pouch foods, confectionery (candy and frozen confectionery, such as ice cream), bread and dumplings, chocolates and processed cocoa products, jams, oils and fats (animal oils and fats, imitation cheese, vegetable cream, and other processed edible oils and fats are excluded), noodles, beverages (excluding roasted coffee and instant coffee among teas and coffees), special-purpose food, fish sausages (processed fish products), convenience foods (foods for instant consumption and ready-to-cook food), Korean sauces, cereals, dairy products (milk, processed milk, fermented milk, powdered milk, cheese), hams and sausages (processed meat products), and functional health food (effective March 2021). The mandatory labeling of 9 nutritional ingredients is as follows: calories, sodium, carbohydrates, sugar, fat, trans fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, and protein. In addition to these 9 nutrients, additional nutrients that are labeled can be expressed as a ‘nutrition claim.’ When labeling nutritional components, the 1) name, 2) content, and 3) ratio (%) of the nutritional component per day must be indicated. In Korea, the violation of NFL rules may result in fines or administrative sanctions (Enforcement Regulations of the Act on Labeling and Advertisement of Food, etc. Article 6 (2) and (3) and Annexed Table 5).

The NFL questionnaire was designed to assess participants’ recognition, reading, and usage of NFLs in dietary decisions. The questionnaire included questions about the number of breakfasts consumed per week, preference for low-salt foods, and experiences with weight control, providing insights into dietary habits and health awareness.

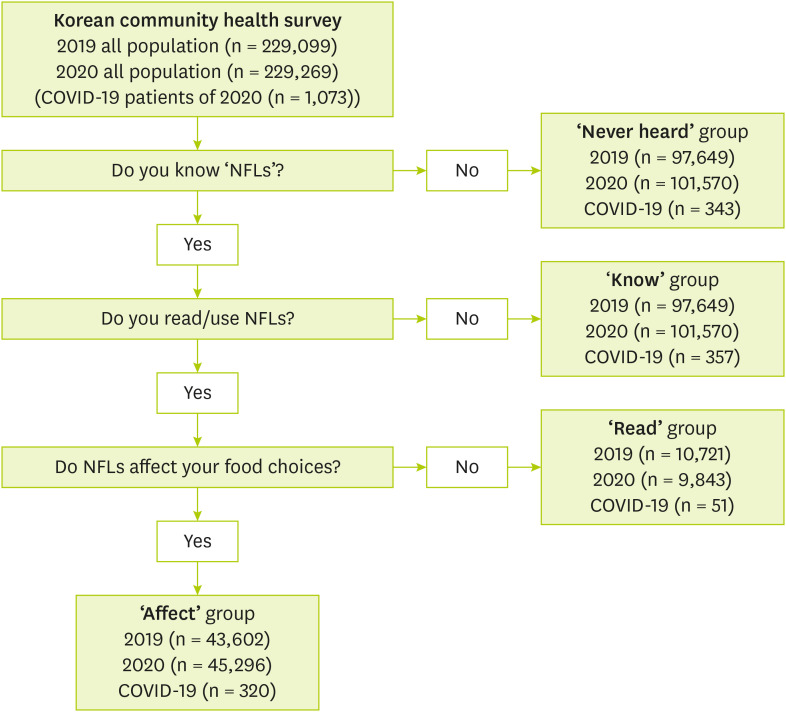

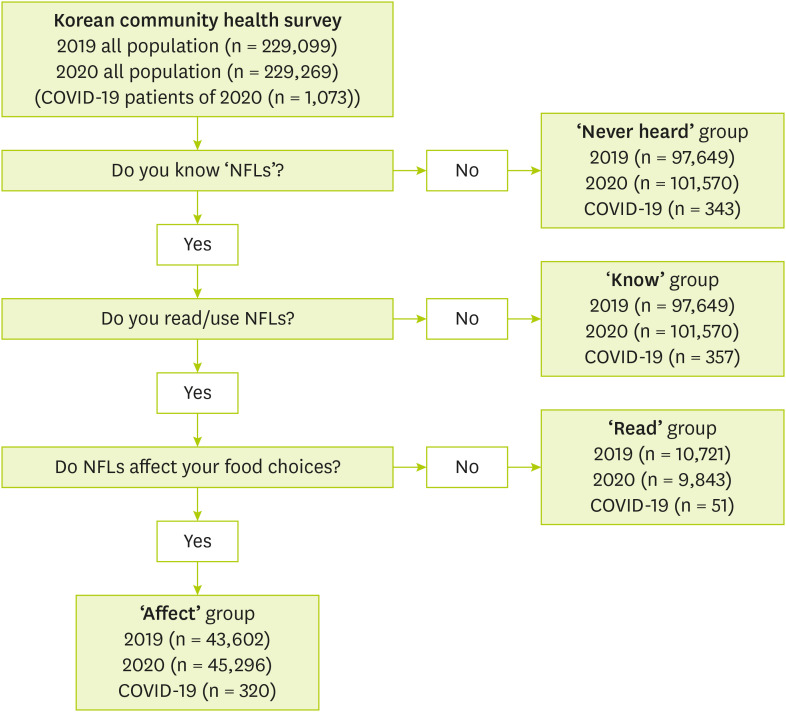

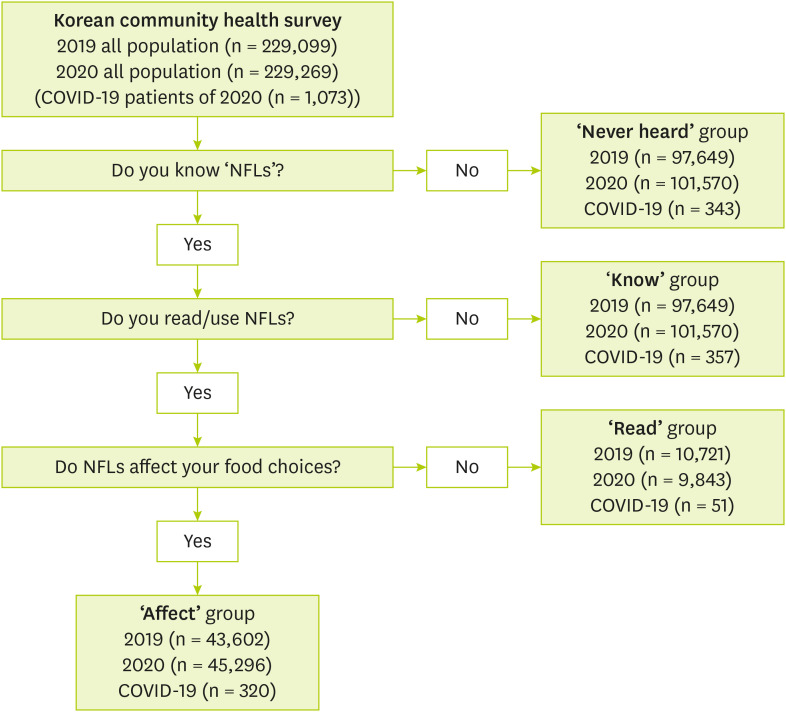

Figure 1 presents a schematic description of the NFL usage questionnaire, categorizing participants into 4 levels of NFL use: affect, read, aware, and never heard. Detailed table layouts and the precise questions from the questionnaire are provided in

Supplementary Table 1 of the supplementary materials, ensuring transparency and allowing for methodological replication. This comprehensive approach enables an in-depth analysis of the relationship between NFL usage and dietary behaviors.

Figure 1

Schematic flow diagram of the level of NFL usage questionnaire.

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; NFL, nutrition fact label.

Medical history and subjective health survey scores

The numbers of vaccinations and health checkups, number of medical facility visits, diagnoses and treatments (stroke, myocardial infarction, hypertension, diabetes mellitus), and history of surgery were surveyed. The subjective health level, quality of life score (Euro Quality of Life-5 Dimension and EuroQol Visual Analog Scale index), and happiness index were also analyzed.

COVID-19 pandemic questionnaire

The study collected comprehensive data on participants’ health and lifestyle changes in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Questions were included to determine if participants had been hospitalized or experienced respiratory symptoms like fever or cough within the past 3 months, as well as to assess personal quarantine practices such as social distancing, disinfection, and mask-wearing. The survey also examined changes in daily life due to the epidemic, including activity restrictions and lifestyle alterations. Specific areas of investigation included changes in sleep duration, fast food and delivered food intake, alcohol consumption, smoking status, frequency of meetings with acquaintances, and use of public transportation. Additionally, the study explored the psychological impact of COVID-19, focusing on concerns about infection, fear of death, social criticism, and economic harm related to the pandemic. The questionnaire’s detailed table layout and exact questions are available in

Supplementary Table 2, providing clarity and enabling a thorough understanding of the data collected.

For general characteristics and survey results, noncontinuous variables are presented as numerical values and percentages, whereas continuous variables are presented as averages and means ± standard deviations. Continuous variables with a normal distribution were analyzed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test to confirm the null hypothesis that a set of data had a normal distribution (age and BMI). In particular, the KCHS data used in this study were national-level sampling data. The KCHS has the advantage of representing the entire population of Korea without being biased/skewed toward a specific demographic group (age, sex, housing type, urban/rural area, etc.) because it extracts stratified samples . The comparisons of mean values among more than 3 groups were performed with analysis of variance tests, and the mean value comparison between 2 groups was tested by independent t-test. The χ2 test was used to analyze the frequencies of categorical variables. Cramér’s V was calculated to measure the effect size of categorical associations. A 2-tailed p value less than 0.05 indicated statistical significance. All data were analyzed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM/SPSS Corp., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Comparison of the level of NFL usage before (2019) and after (2020) the pandemic in the entire population

This analysis was conducted to evaluate the impact of the pandemic on NFL usage.

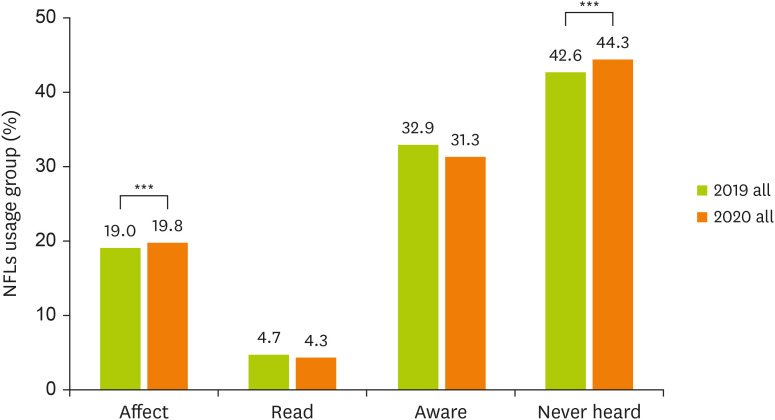

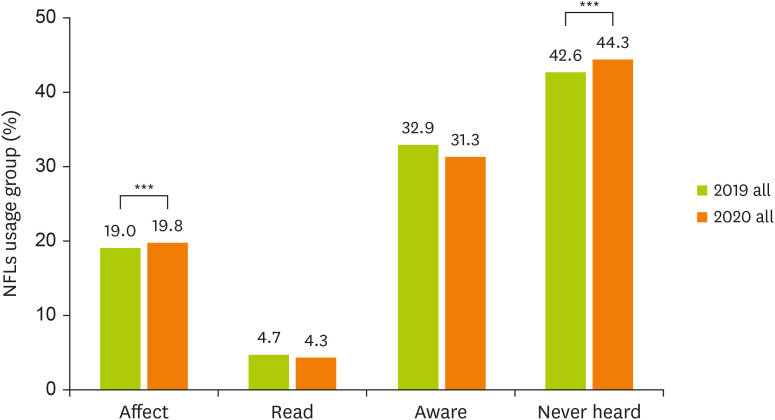

Figure 2 shows an overall comparison of the level of NFL usage during the pre- and pandemic periods in all populations. In the 2019 prepandemic period, 19.0% of the population (n = 43,602) responded that NFLs affected their food choices, but in the 2020 pandemic period, the ratio increased to 19.8% (n = 45,296; p < 0.001). However, 44.3% of all participants in 2020 (n = 101,570) responded that they had never heard of NFLs, which was 1.7% higher than that in 2019 (n = 97,649; p < 0.001). Detailed information on all populations in 2019 (n = 229,099) and 2020 (n = 229,269) is presented in the supporting material (

Supplementary Table 3).

Figure 2

Comparison of the level of NFL usage before (2019, light green) and after (2020, orange) the pandemic in all populations. The p values were derived from χ2 tests between 2019 and 2020 in all population.

NFL, nutrition fact label.

***Significant result with p < 0.001.

Increased level of NFL usage among COVID-19 patients compared with the healthy population during the pandemic (2020)

This analysis aimed to confirm the increased use of NFLs among confirmed COVID-19 patients compared to healthy subjects during the pandemic.

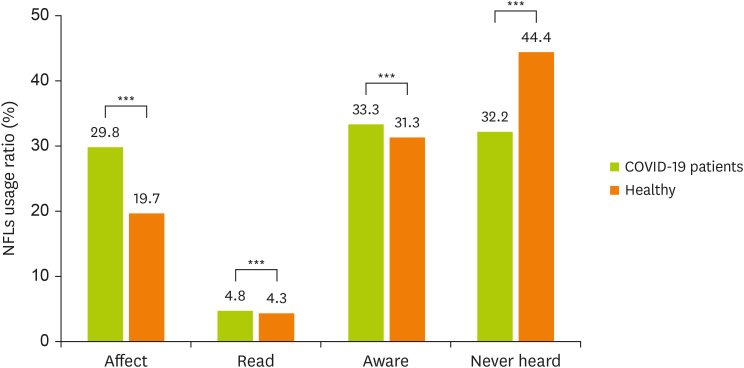

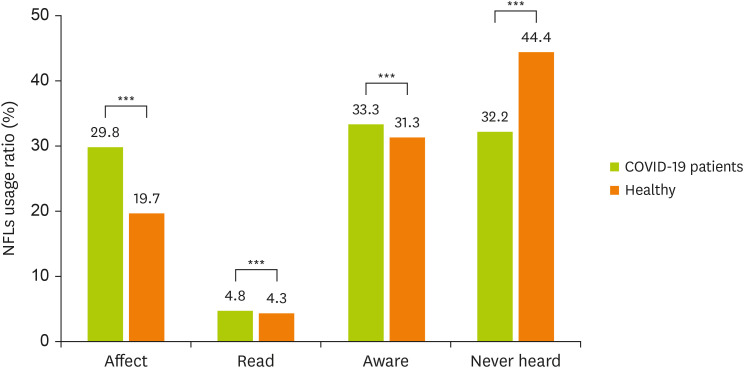

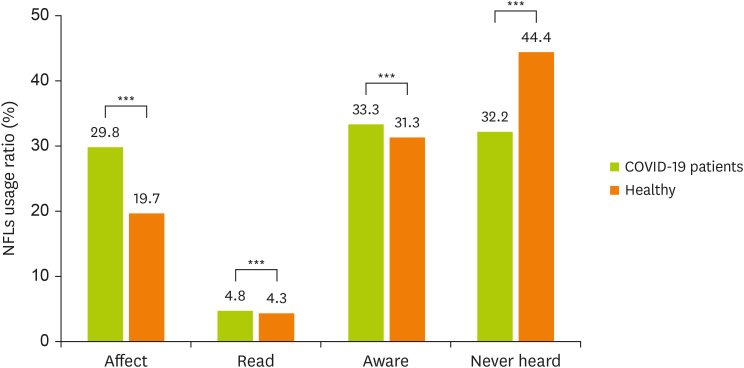

Figure 3 shows that in the case of positive COVID-19 patients, the level of NFL usage increased compared to healthy subjects. Food choices were influenced by the content of NFLs (affect group) for 29.8% of COVID-19 patients, which was 10% higher than the proportion of healthy subjects reported in 2020 (19.7%; p < 0.001). The ratio of subjects classified into the ‘read (4.8%)’ and ‘aware (33.3%)’ groups was higher among COVID-19 patients (p < 0.001).

Figure 3

Comparison of the level of NFL usage between COVID-19 patients (light green) and the healthy population (orange) during the pandemic (2020). The p values were derived from χ2 tests between the COVID-19 patients and healthy adults in 2020.

NFL, nutrition fact label; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

***Significant result with p < 0.001.

Characteristics of quarantined and hospitalized COVID-19 patients

Table 1 outlines the basic characteristics according to NFL usage group. Of the total 1,073 quarantined or hospitalized subjects, 320 subjects were in the “affect” group, 51 subjects were in the “read” group, 357 subjects were in the “aware” group and 343 people were in the “never heard” group. The mean age of all subjects was 48.58 ± 0.53 years, and the oldest group was the never heard group (49.35 ± 18.87 years; p < 0.001). Regarding the area of residence, 38.55% of the never heard group lived in rural areas, whereas 28.44% of the affect group lived in rural areas (p = 0.017).

Table 1Characteristics of quarantined and hospitalized coronavirus disease 2019 patients according to their level of nutrition fact label usage

Table 1

|

Level of nutrition facts label usage |

Total (n = 1,073†) |

High––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Low |

p value |

|

Affect (n = 320) |

Read (n = 51) |

Aware (n = 357) |

Never heard (n = 343) |

|

Ratio (%) |

|

29.82 |

4.75 |

33.27 |

32.15 |

|

|

Age (yr) |

|

|

|

|

|

< 0.001*

|

|

Mean ± SD |

48.58 ± 0.53 |

39.38 ± 14.57 |

39.14 ± 15.31 |

42.41 ± 16.48 |

49.35 ± 18.87 |

|

19–39 |

516 |

183 (57.19) |

30 (58.82) |

173 (48.46) |

130 (37.68) |

|

40–59 |

344 |

107 (33.44) |

14 (27.45) |

123 (34.45) |

100 (28.99 |

|

60+ |

213 |

30 (9.38) |

7 (13.73) |

61 (28.64) |

115 (54.00) |

|

Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

< 0.001*

|

|

Male |

499 |

122 (38.13) |

31 (60.78) |

169 (47.34) |

177 (51.30) |

|

Female |

574 |

198 (61.88) |

20 (39.22) |

188 (52.66) |

168 (48.70) |

|

BMI |

23.66 ± 0.10 |

23.32 ± 3.36 |

23.97 ± 3.01 |

23.71 ± 3.44 |

23.85 ± 3.39 |

0.172 |

|

Region of residence |

|

|

|

|

|

0.017*

|

|

Urban area |

712 |

229 (71.56) |

39 (76.47) |

232 (64.99) |

212 (61.45) |

|

Rural area |

361 |

91 (28.44) |

12 (23.53) |

125 (35.01) |

133 (38.55) |

|

Income (won/yr) |

|

|

|

|

|

< 0.001*

|

|

Low (< 30,000,000) |

260 |

65 (20.31) |

8 (15.69) |

63 (17.65) |

124 (35.94) |

|

Middle (30,000,000–60,000,000) |

378 |

110 (34.38) |

17 (33.33) |

137 (38.38) |

114 (33.04) |

|

High (≥ 60,000,000) |

435 |

145 (45.31) |

26 (50.98) |

157 (43.98) |

107 (31.01) |

|

Smoking |

|

|

|

|

|

0.003*

|

|

Never |

703 |

239 (74.69) |

28 (54.90) |

230 (64.43) |

207 (60.00) |

|

Ex-smoker |

187 |

42 (13.13) |

10 (19.61) |

64 (17.93) |

72 (20.87) |

|

Current smoker |

181 |

39 (12.19) |

13 (25.49) |

63 (17.65) |

66 (19.13) |

|

Alcohol |

|

|

|

|

|

0.023*

|

|

Never |

178 |

44 (24.72) |

8 (4.49) |

56 (31.46) |

70 (39.33) |

|

≤ Once a month |

424 |

155 (36.56) |

20 (4.72) |

125 (29.48) |

124 (29.25) |

|

2–4 times a month |

270 |

84 (31.11) |

102 (37.8) |

13 (4.81) |

71 (26.3) |

|

≥ 2 times a week |

199 |

50 (25.13) |

10 (5.03) |

74 (37.19) |

65 (32.66) |

|

Education level |

|

|

|

|

|

< 0.001*

|

|

Middle school or below |

139 |

14 (10.07) |

3 (2.16) |

38 (27.34) |

84 (60.43) |

|

High school |

248 |

63 (19.69) |

10 (19.61) |

77 (21.57) |

98 (28.41) |

|

College or above |

684 |

243 (75.94) |

38 (74.51) |

212 (59.38) |

161 (46.67) |

|

Obesity |

|

|

|

|

|

0.867 |

|

Underweight |

40 |

14 (4.38) |

2 (3.92) |

15 (4.20) |

9 (2.61) |

|

Normal weight |

444 |

140 (43.75) |

17 (33.33) |

145 (40.62) |

142 (41.16) |

|

Overweight |

243 |

70 (21.88) |

14 (27.45) |

82 (22.97) |

77 (22.32) |

|

Obese |

346 |

96 (30.00) |

18 (35.29) |

115 (32.21) |

117 (33.91) |

|

Diabetes mellitus |

|

13 (4.06) |

3 (5.88) |

33 (9.24) |

36 (10.43) |

< 0.001*

|

|

Hypertension |

|

34 (10.63) |

8 (15.69) |

48 (13.45) |

78 (22.61) |

< 0.001*

|

|

Subjective health status |

|

|

|

|

|

0.017*

|

|

Good |

652 |

184 (57.50) |

31 (60.78) |

234 (65.55) |

203 (58.84) |

|

Normal |

339 |

118 (36.88) |

18 (35.49) |

101 (28.29) |

102 (29.57) |

|

Poor |

82 |

18 (5.63) |

2 (3.92) |

22 (6.16) |

40 (11.59) |

|

Subjective stress level |

|

|

|

|

|

< 0.001*

|

|

None |

219 |

61 (19.06) |

16 (31.37) |

64 (17.93) |

78 (22.61) |

|

Some |

578 |

153 (47.81) |

24 (47.06) |

212 (59.38) |

189 (54.78) |

|

Severe |

218 |

75 (23.44) |

8 (15.69) |

67 (18.77) |

68 (19.71) |

|

Very severe |

58 |

31 (9.69) |

3 (5.88) |

14 (3.92) |

10 (2.90) |

Comparison of daily life change scores

The affect group was considered to have a high utilization of NFLs, the never heard group was considered to have a low utilization of NFLs, and changes in daily life scores according to the level of NFL utilization were compared.

Table 2 shows the differences in the life change scores before the COVID-19 pandemic and after the COVID-19 pandemic between the high-utilization group and the low-utilization group among healthy subjects and COVID-19 patients. The proportion of life change scores of 20 or less (daily life stopped after the pandemic, many changes) was 16.2% in the affect group and 14.2% in the never heard group. The ratio of scores of 80 or higher (daily life did not change, same as daily life before the pandemic) was 11.2% in the affect group and 14.5% in the never heard group, showing the opposite trend (Cramér’s V = 0.188; p = 0.024). However, in the healthy population, the proportion of life change scores of 20 or less was 11.8% in the affect group and 8.9% in the never heard group, resulting in healthy subjects’ subjective daily life scores being less affected by the pandemic compared to those of COVID-19 patients.

Table 2Comparison of daily life change scores according to the level of nutrition fact label usage (If your daily life score before the COVID-19 outbreak was 100 points, what is your current daily life score?)

Table 2

|

Level of nutrition facts label usage |

Score*

|

High utilization |

Low utilization |

Cramér’s V |

|

Affect |

Never heard |

|

COVID-19 patients |

|

(n = 320) |

(n = 345) |

0.188 (p = 0.024) |

|

Completely stopped (everything changed) |

0 |

11 (3.4) |

8 (2.3) |

|

|

| |

10 |

11 (3.4) |

23 (6.7) |

|

|

| |

20 |

30 (9.4) |

18 (5.2) |

|

|

| |

30 |

41 (12.8) |

43 (12.5) |

|

|

| |

40 |

24 (7.5) |

33 (9.6) |

|

|

| |

50 |

82 (25.6) |

87 (25.4) |

|

|

| |

60 |

37 (11.6) |

39 (11.4) |

|

|

| |

70 |

47 (14.7) |

41 (12.0) |

|

|

| |

80 |

23 (7.2) |

25 (7.3) |

|

|

| |

90 |

11 (3.4) |

8 (2.3) |

|

Same as before the COVID-19 outbreak (nothing changed) |

100 |

2 (0.6) |

17 (5.0) |

|

Healthy subjects |

|

(n = 44,976) |

(n = 101,227) |

0.130 (p < 0.001) |

|

Completely stopped (everything changed) |

0 |

762 (1.7) |

2,121 (2.1) |

|

|

| |

10 |

1,604 (3.6) |

2,540 (2.5) |

|

|

| |

20 |

2,904 (6.5) |

4,316 (4.3) |

|

|

| |

30 |

5,769 (12.8) |

8,942 (8.8) |

|

|

| |

40 |

3,880 (8.6) |

7,585 (7.5) |

|

|

| |

50 |

11,229 (25.0) |

25,475 (25.2) |

|

|

| |

60 |

5,401 (12.0) |

11,394 (11.3) |

|

|

| |

70 |

5,896 (13.11) |

13,102 (12.9) |

|

|

| |

80 |

4,187 (9.3) |

11,220 (11.1) |

|

|

| |

90 |

1,739 (3.9) |

5,884 (5.8) |

|

Same as before the COVID-19 outbreak (nothing changed) |

100 |

1,497 (3.3) |

7,563 (7.5) |

Changes in eating habits

Table 3 shows an increase in unfavorable changes in the consumption of fast food, soda, delivered food and physical activity among COVID-19 patients compared with those in the pre-COVID-19 outbreak period according to the level of NFL usage. In the affect group, the proportion of respondents who reported that their consumption of delivered food increased was 38.7% among COVID-19 patients, which was 17.1% higher than that in the never heard group (Cramér’s V = 0.257; p < 0.001). The proportion of respondents who reported that their fast food and soda intake increased was 24.7% in the affect group among COVID-19 patients, which was 15.1% higher than that in the never heard group (Cramér’s V = 0.170; p < 0.001). The proportions of COVID-19 patients who reported decreased physical activity were more than 50% in both the affect and never heard groups (Cramér's V = 0.167; p < 0.001). However, healthy subjects were less likely to be affected by unfavorable eating habit changes and a decrease in physical activity.

Table 3Changes in the consumption of fast food, soda, and delivered food and physical activity compared to the prepandemic period

Table 3

|

Level of nutrition facts label usage |

High utilization |

Low utilization |

Cramér’s V |

|

Affect |

Never heard |

|

COVID-19 patients*

|

(n = 320) |

(n = 345) |

|

|

Consumption of delivered food |

|

|

0.257 (p < 0.001) |

|

|

Increased |

124 (38.8) |

75 (21.7) |

|

|

Same |

92 (28.8) |

102 (29.7) |

|

|

Decreased |

41 (12.8) |

27 (7.9) |

|

Consumption of fast food and soda |

|

|

0.170 (p < 0.001) |

|

|

Increased |

79 (24.7) |

52 (15.2) |

|

|

Same |

136 (42.5) |

149 (43.4) |

|

|

Decreased |

35 (10.9) |

25 (7.3) |

|

Physical activity |

|

|

0.167 (p < 0.001) |

|

|

Increased |

29 (9.1) |

23 (7.0) |

|

|

Same |

84 (26.3) |

109 (31.9) |

|

|

Decreased |

199 (62.2) |

179 (51.9) |

|

Healthy subjects*

|

(n = 44,976) |

(n = 101,227) |

|

|

Consumption of delivered food |

|

|

0.268 (p < 0.001) |

|

|

Increased |

13,814 (30.7) |

13,113 (13.0) |

|

|

Same |

13,617 (30.3) |

24,183 (23.9) |

|

|

Decreased |

3,640 (8.1) |

5,930 (5.9) |

|

Consumption of fast food and soda |

|

|

0.209 (p < 0.001) |

|

|

Increased |

7,960 (17.7) |

7,782 (7.7) |

|

|

Same |

20,084 (44.7) |

38,659 (38.2) |

|

|

Decreased |

4,735 (10.5) |

7,779 (7.7) |

|

Physical activity |

|

|

0.189 (p < 0.001) |

|

|

Increased |

3,038 (6.8) |

4,457 (4.4) |

|

|

Same |

16,168 (35.9) |

49,539 (48.9) |

|

|

Decreased |

23,789 (52.9) |

36,152 (35.7) |

DISCUSSION

In the current study, compared to that in the prepandemic period, the proportion of subjects who responded that NFLs affected their food choices increased, mainly among people with COVID-19. This tendency increased as unfavorable daily life changes became more severe. Then, what factors, according to the findings of our study, contributed to the increase in overall NFL usage among all participants during the pandemic, and why did quarantined COVID-19 patients engage with NFL more extensively than their healthy populations?

We hypothesize that for patients who have experienced COVID-19, the effort to seek information may have led to the use of NFL. This result of the search for nutrition information during the pandemic is in line with the results of an East Asian study. Luo et al. [

3] confirmed that 73.4% of participants paid attention to nutrition and immunity-related knowledge during the COVID-19 pandemic. Among the participants, 94.3% thought that improving nutrition could prevent COVID-19, and 52.1% responded that they were willing to receive advice on how to improve their diet. The COVID-19 pandemic caused an “infodemic” of diverse information and sources. To date, no study has directly evaluated the efficacy of NFLs during the pandemic; however, a higher level of health literacy increased the likelihood of healthier eating behaviors during the pandemic [

14]. Duong et al. [

14] reported that literacy score increments were associated with 18%, 23%, and 17% increased likelihoods of healthier eating behaviors during the pandemic for the overall sample (odds ratio [OR], 1.18; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.13–1.24; p < 0.001), nursing students (OR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.10–1.35; p < 0.001), and medical students (OR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.11–1.24; p < 0.001), respectively. In addition, the framework of the World Health Organization stated that information on COVID-19 should be translated into actionable behavioral change messages presented in ways that are understood by and accessible to all individuals in all parts of all societies, and health authorities should ensure that these actions are informed by reliable information.

Another novel aspect of this study is that utilization of NFLs according to subjective daily life scores and changes in eating habits was analyzed. In this study, those who reported an increase in delivered and fast food consumption reported higher NFL utilization, which is consistent with findings from previous studies [

15]. With the outbreak of a disease that requires isolation, all aspects of human life are adversely affected, and these changed aspects can lead to changes in food consumption patterns (delivered and fast food consumption, etc.) [

16]. A previous study conducted using artificial intelligence also revealed that the COVID-19 pandemic changed food consumption patterns [

17]. In particular, in terms of food types, the use of pulse crops, pancakes/tortillas/oatcakes and soup/pottage obviously increased during the COVID-19 pandemic by 300%, 280% and 100%, respectively, in food preparation recipes. In addition, pandemic-related stress causes patients to excessively consume “comfort foods” that are high in sugar, resulting in higher energy intake as a form of “emotional eating” in quarantine situations [

18].

Several studies have shown potential opportunities for utilizing NFLs in public health. NFLs on prepackaged foods are a population-level intervention with an unparalleled reach [

19,

20], and knowledge of diet–disease relationships and increased optimal self-selectivity have also been associated with NFL use. Furthermore, diagnosis or awareness of a disease [

21] has also been associated with greater NFL use. Policy-based (regulated by government) and population-wide information such as NFLs is likely to offer cost-effective measures [

22]. Although there is a lack of research regarding actual cost-effectiveness analyses of the NFL effect in pandemics, Sacks et al. [

22] evaluated the effectiveness of ‘traffic-light’ nutrition labeling for obesity prevention in Australia. Traffic-light labeling resulted in reduced mean weight (1.3 kg; 95% uncertainty interval [UI], 1.2–1.4) and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) averted (alcohol use disorder, 45,100; 95% UI, 37,700–60,100). The cost outlays were Australian Dollar 81 million (95% UI, 44.7–108.0) for traffic-light labeling. Therefore, in that study, the net cost per DALY averted (with cost offsets) was dominant (effective and cost-saving). Because it was conducted for different diseases and social circumstances, it is difficult to simply generalize the experiment to Korea’s pandemic situation. However, it is meaningful to discuss the fact that NFLs themselves are a cost-effective method in health policy. In this context, conventional NFLs provided on food packaging were the only “accessible”, “attention-grabbing”, and “cost-effective way” [

22] to disseminate nutrition information during the pandemic.

The major limitation of this study includes the inability to analyze how COVID-19 patients’ nutrition intake were affected by nutritional facts. Whether the NFL was accurately interpreted and how it influenced food choices (e.g., whether high-calorie foods were replaced with low-calorie foods or whether foods with high or low levels of certain nutrients [simple sugar, saturated fat, protein, minerals, etc.] were selected) remained unknown among confirmed COVID-19 patients and healthy individuals during the pandemic period. In addition, an actual nutritional intake analysis was not conducted; therefore, the current study could not investigate nutritional intake or nutritional risk according to the utilization of NFLs. Therefore, to enhance readers’ in-depth understanding, we included a brief discussion on whether the increased NFL usage positively influenced actual dietary intake.

Several studies have reported that increased utilization of NFLs translates into unequivocally improved eating behaviors. Buyuktuncer et al. [

23] suggested an association between NFL use and Healthy Eating Index 2005 (HEI-2005) scores. They indicated that the mean HEI-2005 scores were 60.7 ± 10.11, 62.4 ± 11.43 and 67.1 ± 12.23 for never, sometimes and every time users of NFLs, respectively, which shows that HEI-2005 scores were significantly associated with NFL use. Another previous study proved that nutritional intake among younger subjects (age groups of 20–39 years and 40–59 years) who reported using NFL information to make food choices was better (improved) than that among those who said they simply read NFLs [

24]. In this study, more than 90% of those who used NFL information to make food choices were COVID-19 patients under 59 years of age.

To present the beneficial effect of NFL use and healthy diets and the association between label use and lower fat consumption, NFL users are also more likely to eat a larger variety of healthier foods [

24], consume less salt (Na) [

25], have relatively low cholesterol, have low energy intake, have increased fiber intake [

26], have improved micronutrient intake, such as iron (Fe) and vitamin C intake, have reduced total energy intake, and consume low-density food [

27]. Although rigorous clinical trials conducted to elaborate upon and confirm the benefits of a healthy diet in the current COVID-19 pandemic are still lacking, several studies have shown a well-established consensus on strengthening the immune system and reducing inflammation and oxidative stress through diet and nutrition for combating the COVID-19 crisis . Varied and balanced diets improve the immune response to viral infection and reduce prognosis severity and complications . Additionally, vitamin C [

28] and vitamin D [

29] supplementation can be plausible as a method to prevent adverse symptoms of respiratory infections

. Taken together, the results of previous studies suggest that the higher utilization of NFLs by COVID-19 patients leads to better nutrition intake.

Furthermore, we propose the following highly specific research methods to address these limitations. Future studies should evaluate differences in COVID-19 patients’ actual intake according to NFL use through 24-hour recall or food frequency questionnaires. Considering that more than half of the Korean population (25 million) reported having had a medically confirmed COVID-19 infection, as of October 2022, from the Korea Ministry of Health and Welfare and even in the database without a separation of confirmed cases, we can assume that most of the raw data after 2022 are the results of confirmed patients. For future research possibilities, for example, 2021 and 2022 data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (the only weighted national survey that uses the 24-hour recall method and includes 5,000–8,000 survey participants annually by the KCDC) can show actual COVID-19-related nutritional intake changes.

Another limitation was the inability to ascertain causality, given the cross-sectional nature of this study. As in many previous studies, it was not possible to determine the motivation for NFL use or vice versa. This could not be investigated due to the small number of confirmed COVID-19 cases and different socioeconomic backgrounds of the patients. Nevertheless, as mentioned in the above discussion, the pandemic situation and confirmation of the disease in a patient can be major reasons for the heightened awareness of NFLs.

Last, as COVID-19 is a newly emerged epidemic disease, studies on individual differences in the severity of symptoms and prognoses according to living environment are lacking. Therefore, it was not possible to show NFL utilization stratified by the severity of symptoms (respiratory diseases, systemic diseases, depression, etc.). In addition, since isolation and social policies related to the pandemic, including stay-at-home mandates to reduce social contact, regulations to control the spread of the virus, medical system changes, and quarantine guidelines, are variable among countries, caution must be taken in generalizing the results, as this study was conducted in a single country (Korea). The COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing, and the nature of the disease is constantly changing. These results need to be confirmed and reviewed further in a larger population and in multinational studies.

The more pronounced shift towards unfavorable daily life changes and increased NFL usage among COVID-19 confirmed individuals, as opposed to healthy adults, indicates a significant impact of the pandemic on the dietary habits. This highlights the critical need for targeted nutritional interventions for COVID-19 patients, who exhibit a heightened vulnerability to detrimental alterations in eating behaviors and physical activity levels. Integrating NFL education into clinical care can play a pivotal role in alleviating these negative impacts, thereby fostering healthier dietary choices and enhancing overall patient outcomes during the recovery phase from COVID-19 or other infectious influenza diseases requiring isolation. Despite the above limitations, the findings indicated that NFLs are an effective way to provide nutritional information in a pandemic situation, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrated that people who experienced a greater number of unfavorable changes in daily life due to COVID-19 had a higher rate of nutritional information seeking, leading to an increase in the use of NFLs. The potential implication of this study is that it highlights opportunities for utilizing NFLs in public health and cost-effective nutritional policy development in a future pandemic situation.

National Research Foundation of Koreahttps://doi.org/10.13039/501100003725

2022R1I1A1A01066215

NOTES

-

Funding: This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2022R1I1A1A01066215). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection or analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

-

Availability of Data and Materials: The data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon reasonable request (Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency at https://chs.kdca.go.kr/).

-

Author Contributions:

Conceptualization: Cho JM, Baek HI.

Data curation: Cho JM.

Formal analysis: Cho JM.

Funding acquisition: Cho JM.

Investigation: Cho JM, Baek HI.

Methodology: Cho JM, Baek HI.

Project administration: Cho JM.

Resources: Cho JM.

Software: Cho JM.

Supervision: Cho JM, Baek HI.

Validation: Cho JM, Baek HI.

Visualization: Cho JM, Baek HI.

Writing - original draft: Cho JM.

Writing - review & editing: Cho JM, Baek HI.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary Table 3

Characteristics of participants in the 2019–2020 Korean Community Health Survey

cnr-14-100-s003.xls

REFERENCES

- 1. Kaya S, Uzdil Z, Cakiroğlu FP. Evaluation of the effects of fear and anxiety on nutrition during the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. Public Health Nutr 2021;24:282-289.

- 2. Lee M. Nutrition agenda during the era of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Nutr Health 2021;54:1-9.

- 3. Luo Y, Chen L, Xu F, Gao X, Han D, et al. Investigation on knowledge, attitudes and practices about food safety and nutrition in the China during the epidemic of corona virus disease 2019. Public Health Nutr 2021;24:267-274.

- 4. Okan O, Bollweg TM, Berens EM, Hurrelmann K, Bauer U, et al. Coronavirus-related health literacy: a cross-sectional study in adults during the COVID-19 infodemic in Germany. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:5503.

- 5. Rayner M, Scarborough P, Williams C. The origin of guideline daily amounts and the Food Standards Agency’s guidance on what counts as ‘a lot’ and ‘a little’. Public Health Nutr 2004;7:549-556.

- 6. Kang YW, Ko YS, Kim YJ, Sung KM, Kim HJ, et al. Korea community health survey data profiles. Osong Public Health Res Perspect 2015;6:211-217.

- 7. Kim YT, Choi BY, Lee KO, Kim H, Chun JH, et al. Overview of Korean community health survey. J Korean Med Assoc 2012;55:74-83.

- 8. Lange SJ, Kompaniyets L, Freedman DS, Kraus EM, Porter R, et al. Longitudinal trends in body mass index before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among persons aged 2–19 years—United States, 2018–2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:1278-1283.

- 9. World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. 2020. cited 2023 March 10. Available from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

- 10. Kreuter MW, Brennan LK, Scharff DP, Lukwago SN. Do nutrition label readers eat healthier diets? Behavioral correlates of adults’ use of food labels. Am J Prev Med 1997;13:277-283.

- 11. Kollannoor-Samuel G, Shebl FM, Hawley NL, Pérez-Escamilla R. Nutrition label use is associated with lower longer-term diabetes risk in US adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;105:1079-1085.

- 12. Christoph MJ, An R, Ellison B. Correlates of nutrition label use among college students and young adults: a review. Public Health Nutr 2016;19:2135-2148.

- 13. Park HK. Nutrition policy for nutrition labeling in Korea. Food Ind Nutr 2009;14:9-14.

- 14. Duong TV, Pham KM, Do BN, Kim GB, Dam HT, et al. Digital healthy diet literacy and self-perceived eating behavior change during COVID-19 pandemic among undergraduate nursing and medical students: a rapid online survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:7185.

- 15. Bae YJ, Park SY, Bak HR. Evaluation of dietary quality and nutritional status according to the use of nutrition labeling and nutrition claims among university students in Chungbuk area - Based on nutrition quotient. Korean J Community Nutr 2020;25:179-188.

- 16. Janssen M, Chang BPI, Hristov H, Pravst I, Profeta A, et al. Changes in food consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic: analysis of consumer survey data from the first lockdown period in Denmark, Germany, and Slovenia. Front Nutr 2021;8:635859.

- 17. Eftimov T, Popovski G, Petković M, Seljak BK, Kocev D. COVID-19 pandemic changes the food consumption patterns. Trends Food Sci Technol 2020;104:268-272.

- 18. Moynihan AB, van Tilburg WA, Igou ER, Wisman A, Donnelly AE, et al. Eaten up by boredom: consuming food to escape awareness of the bored self. Front Psychol 2015;6:369.

- 19. Campos S, Doxey J, Hammond D. Nutrition labels on pre-packaged foods: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr 2011;14:1496-1506.

- 20. Jadapalli M, Somvarapu S. A survey on perception of food labels among the population of Nellore district. American J Food Sci Nutr 2018;5:1-16.

- 21. McArthur L, Chamberlain V, Howard AB. Behaviors, attitudes, and knowledge of low-income consumers regarding nutrition labels. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2001;12:415-428.

- 22. Sacks G, Veerman JL, Moodie M, Swinburn B. ‘Traffic-light’ nutrition labelling and ‘junk-food’ tax: a modelled comparison of cost-effectiveness for obesity prevention. Int J Obes 2011;35:1001-1009.

- 23. Buyuktuncer Z, Ayaz A, Dedebayraktar D, Inan-Eroglu E, Ellahi B, et al. Promoting a healthy diet in young adults: the role of nutrition labelling. Nutrients 2018;10:1335.

- 24. Nayga RM Jr. Retail health marketing: evaluating consumers’ choice for healthier foods. Health Mark Q 1999;16:53-65.

- 25. Fitzgerald N, Damio G, Segura-Pérez S, Pérez-Escamilla R. Nutrition knowledge, food label use, and food intake patterns among Latinas with and without type 2 diabetes. J Am Diet Assoc 2008;108:960-967.

- 26. Variyam JN. Do nutrition labels improve dietary outcomes? Health Econ 2008;17:695-708.

- 27. Kral TV, Roe LS, Rolls BJ. Does nutrition information about the energy density of meals affect food intake in normal-weight women? Appetite 2002;39:137-145.

- 28. Simonson W. Vitamin C and coronavirus. Geriatr Nurs 2020;41:331-332.

- 29. Carter SJ, Baranauskas MN, Fly AD. Considerations for obesity, vitamin D, and physical activity amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28:1176-1177.