ABSTRACT

Adequate nutrition reportedly can help reduce the degree of muscle loss and improve muscle quality in hospitalized patients recovering from trauma. This study investigated the association between nutritional intake and changes in muscle quality and quantity in these patients. The handgrip strength (HGS) and body composition of 52 patients admitted to the trauma ward were measured at 1-week intervals. According to their dietary intake, they were categorized into the hypocaloric nutrition group (HNG; < 70% of recommended caloric intake) and the isocaloric nutrition group (ING; ≥ 70% of recommended caloric intake). Within one week, body mass index (24.3 ± 4.4 kg/m2 vs. 23.4 ± 4.5 kg/m2), body fat percentage (24.1% ± 9.8% vs. 17.2% ± 9.2%), and skeletal muscle mass (28.6 ± 4.9 kg vs. 27.5 ± 4.3 kg) significantly decreased in the ING compared with those in the HNG. Although the skeletal muscle mass decreased, the ING’s left HGS significantly increased (26.6 ± 9.6 kg vs. 28.5 ± 10.1 kg). The ING also consumed a significantly greater amount of protein (beyond the recommended amount) than the HNG (72.6 ± 43.2 → 100.8 ± 27.0% vs. 58.6 ± 25.9 → 49.5 ± 20.1%; p = 0.039). In bioelectrical impedance vector analysis, the vectors of the ING shifted more within the normal range of the 75% tolerance ellipse than those of the HNG (23% vs. 10%). These results suggest that, although the muscle mass quantitatively decreased during trauma recovery, adequate nutritional support helps preserve muscle quality.

-

Keywords: Trauma; Muscle; Body composition; Nutritional intake

INTRODUCTION

Most patients with trauma experience severe metabolic exhaustion, losing large amounts of muscle within a short period after injury and surgery. Additionally, trauma- or stress-induced multiple organ failure leads to sustained metabolic reactions, which cause protein loss in the body. These metabolic reactions reportedly persist even after recovery from trauma or stress, further depleting the body’s protein reserves [

1,

2]. Reduced muscle strength exacerbates physical decline, thereby negatively affecting recovery after a disease or surgery. Muscle function is closely related to protein quantity in the body [

3,

4]. A decrease in muscle strength caused by muscle mass loss can result in diseases associated with malnutrition, further reducing protein synthesis in the body [

5]. An appropriate level of muscle strength and mass needs to be maintained for proper physical functioning. Muscle strength is an indicator of muscle quality, whereas muscle mass is an indicator of muscle quantity. A loss of muscle mass has been associated with various physical disorders and diseases, as well as mortality [

6,

7,

8]. Furthermore, reduced handgrip strength (HGS) strongly correlates with postoperative complications and may predict the length of hospital stay, loss of function, and short-term survival among hospitalized patients [

9].

Mohamed-Hussein et al. [

10] reported that HGS can effectively predict the outcomes of weaning from mechanical ventilation and length of hospital stay among critically ill patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Given that HGS measurement was reported to be the simplest way to evaluate muscle strength, especially for bedridden patients, it has been widely used clinically to predict nutritional status, functional strength, and mortality risk. This method is a noninvasive, reliable, and simple means of assessing muscle strength and nutritional status [

11].

Low HGS was reported to be associated with cardiovascular disease [

12], diabetes [

13], and metabolic disease [

14]. It is an objective indicator of frailty syndrome among older adults and the most frequently used clinical indicator of muscle function; it is also applied for predicting mortality risk in older patients [

15]. Kim et al. [

16] stated that low HGS significantly correlates with osteopenia and fracture among healthy postmenopausal women in Korea.

In patients recovering from trauma, quantitative losses of body weight and muscle mass are frequently observed because of ongoing metabolic responses, even when nutritional intake is increased. Therefore, measuring only the change in body weight, a typical quantitative evaluation method, does not precisely assess the nutritional status of these patients. Hence, this study aimed to examine the association between the level of nutritional intake and alterations in muscle quality and body composition among patients recovering from trauma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and design

This study enrolled 52 patients aged 18 years and over (38 men and 14 women) who were admitted to the trauma ward within 2 weeks of their initial hospitalization between May and December 2019. Patients who could not undergo bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) because of an arm injury, leg cast, or abnormal mental status, such as reduced consciousness, were excluded. The Ajou University Institutional Review Board of AJIRB-MED-SUR-18-365 approved this study.

General characteristics

The mean length of stay for each participant in the trauma center was 17 days. HGS and BIA were measured at baseline and follow-up in the trauma general ward twice a week. The mean length of hospital stay for all participants was 21.0 ± 12.8 days. Data collected from the electronic medical records included the following: sex, age, height, weight, occupation, reason for hospitalization, nutritional supply route, Injury Severity Score (ISS), Acute Physiologic Assessment and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) score, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, length of hospital stay, and number of surgeries. Data on blood test results, including those of total lymphocyte count (TLC), C-reactive protein (CRP), and serum albumin, and anthropometric data, namely, height, body weight, and nutritional intake, were also collected whenever HGS and BIA were measured.

Nutritional support assessment

The clinical dietitians assessed patients’ nutritional intake through the 24-hour recall method and investigated their enteral nutrition (EN) and intravenous nutrition on each day of HGS and BIA measurements. To determine the recommended amount for calories and protein for each patient, the assigned dietitian used an equation in accordance with the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism guidelines. The recommended caloric intake was 25–30 kcal/kg/day, while the recommended protein intake was 1.2–2.0 g/kg/day [

17,

18]. Subsequently, the actual/recommended nutritional intake ratio was calculated by comparing the patient intakes with the recommendations.

On the BIA’s coordinate plane, the impedance vector represents the sum of resistance (

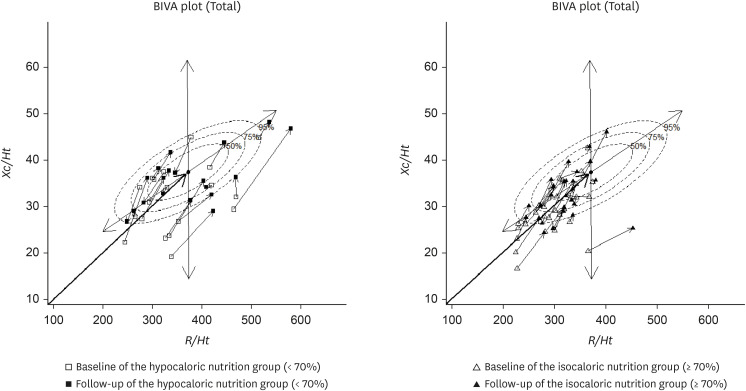

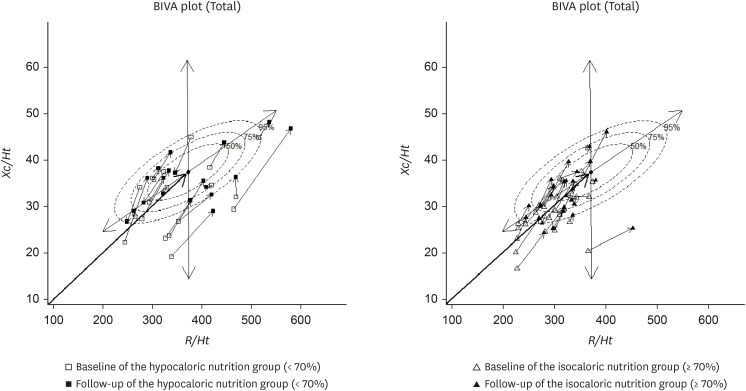

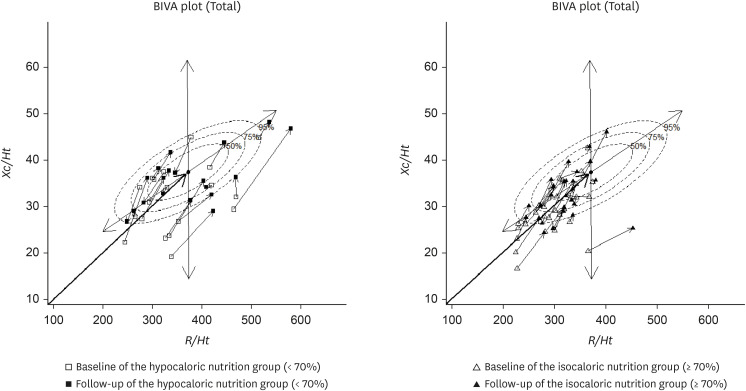

R) and reactance (

Xc), plotted along the x-axis and y-axis, respectively. It can be used to determine the total body water content, body shape, body composition, and nutritional status [

19]. In bioelectrical impedance vector analysis (BIVA), tolerance ellipses at the 50th, 75th, and 95th percentiles are derived from a reference population of healthy adults. These ellipses represent the bivariate distribution of

R and

Xc, which have been standardized by height. The 50% ellipse encompasses the central distribution of vectors among healthy individuals, the 75% ellipse includes a wider but still normal range, and the 95% ellipse defines the outer boundary of the normal vector distribution.

Patients were positioned as close to upright as possible, with the shoulders in a neutral position, arms at the sides, and elbow flexion of 90°. The dominant hand’s HGS was measured serially using an adjustable handheld dynamometer (Jamar Plus digital hand dynamometer; Sammons Preston, Chicago, IL, USA) at the same time every day. All patients were right-handed. First, the facilitator demonstrated how to grip the dynamometer and encouraged the patients to practice. Then, in accordance with the user manual, the patients gripped the dynamometer at maximum strength for 2–3 seconds, with a break of 30 seconds between trials. The highest HGS after 3 consecutive trials was recorded [

10].

For BIA, a body composition analyzer (InBody S10; Biospace, Seoul, Korea) was used. During measurements, the patient lay in the supine position with the arms spreading naturally at approximately 15° angle from the trunk and feet shoulder-width apart, ensuring the thighs did not touch. Both wrists and ankles were swabbed with alcohol, clips were applied, and electrodes were connected.

Nutritional status assessment

On hospitalization, the following potential patient risk factors were examined: age, body mass index (BMI), serum albumin level, malnutrition symptoms (unintentional weight loss in the last month, dysphagia, difficulty chewing, fasting for ≥ 3 days, appetite loss for ≥ 2 weeks, and oral feeding), and diseases associated with high malnutrition risk (renal failure, liver cirrhosis, hepatic coma, congenital metabolic diseases, bedsores, multiple trauma, burns ≥ 10% of the total body surface area, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). The patients were divided into low-, medium-, and high-risk malnutrition groups. On the basis of the assessment results, the low-risk malnutrition group was classified as “well nourished,” while the medium- and high-risk groups were classified as “malnourished.”

Statistical analysis

Statistical data were analyzed using SPSS software (ver. 25.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The participants’ general characteristics were examined by t-test and χ

2 test according to sex. The participants were also divided into HGS-increase and HGS-decrease groups and into isocaloric and hypocaloric nutrition groups (ING and HNG: ≥ 70% and < 70% of the recommended caloric intake, respectively). A paired t-test was conducted within each group, followed by an unpaired t-test to compare the percent change between 2 groups. The status and changes in body composition of the ING and HNG were assessed using BIVA [

19]. Correlations among factors were examined by Pearson correlation analysis. In all analyses, a p value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the total patient population

Table 1 shows the participants’ general characteristics. The study population consisted of 38 men (73.1%) and 14 women (26.9%), with a mean age of 53.7 ± 16.7 years and a mean BMI of 24.2 ± 4.3 kg/m

2. According to the labor intensity of their occupations, the majority were engaged in mild-intensity work (40.4%), followed by high-intensity work (28.8%). The most common reason for hospitalization was traffic accident (44.2%), followed by falls (34.6%). The mean scores for GCS, ISS, and APACHE II were 13.8 ± 3.4, 19.4 ± 8.7, and 7.7 ± 5.0 points, respectively. Regarding the nutritional route, oral-only route (63.5%) was the most common, followed by the combination of parenteral nutrition (PN) and oral route (28.8%) and PN alone (3.9%), with only one patient (1.9%) receiving EN and PN and one patient (1.9%) receiving EN alone. The mean length of intensive care unit (ICU) stay was 3.3 ± 2.6 days, while the mean length of hospital stay was 21.0 ± 12.8 days. In terms of nutritional status, 75% of the participants were well nourished, and 25% were malnourished. The mean number of surgeries was 1.0 ± 0.9. According to BIA, the number of patients with low appendicular skeletal muscle mass (male: < 7.0 kg/m

2, female: < 5.7 kg/m

2) increased from 10 (19.2%) at baseline to 12 (23.1%) at the 1-week follow-up. Additionally, the number of patients with sarcopenia, that is, low muscle strength (male: < 28 kg, female: < 18 kg) or low appendicular skeletal muscle mass based on BIA (male: < 7.0 kg/m

2, female: < 5.7 kg/m

2), increased from 6 (11.5%) at baseline to 8 (15.8%) the following week.

Table 1Baseline characteristics

Table 1

|

Patient characteristics |

Total (n = 52, 100%) |

|

Age (yr) |

53.7 ± 16.7 |

|

Male |

38 (73.1) |

|

Height (cm) |

168.8 ± 24.2 |

|

Weight (kg) |

68.2 ± 13.6 |

|

Body mass index (kg/m2) |

24.2 ± 4.3 |

|

Labor intensity of occupation |

|

|

Low |

16 (30.8) |

|

Moderate |

21 (40.4) |

|

High |

15 (28.8) |

|

Reason for hospitalization |

|

|

Traffic accidents |

23 (44.2) |

|

Fall/slip down |

18 (34.6) |

|

Crash and penetration |

9 (17.3) |

|

Other |

2 (3.9) |

|

Injury Severity Score |

19.4 ± 8.7 |

|

Glasgow Coma Scale |

13.8 ± 3.4 |

|

APACHE II score |

7.7 ± 5.0 |

|

Diet type |

|

|

Oral diet |

33 (63.5) |

|

PN |

2 (3.9) |

|

PN & EN |

1 (1.9) |

|

PN & oral diet |

15 (28.8) |

|

EN |

1 (1.9) |

|

Length of intensive care unit stay (days) |

3.3 ± 2.6 |

|

Length of hospital stay (days) |

21.0 ± 12.8 |

|

Nutritional status |

|

|

Well nourished |

39 (75) |

|

Malnourished |

13 (25) |

|

No. of operations |

1.0 ± 0.9 |

|

Sarcopenia*

|

|

|

Baseline |

6 (11.5) |

|

Follow-up |

8 (15.4) |

Changes in HGS, body composition, and other factors according to sex

Compared with those at baseline, weight (71.0 ± 12.6 kg vs. 68.5 ± 12.3 kg; p < 0.001) and BMI (24.0 ± 3.8 kg/m

2 vs. 23.2 ± 3.8 kg/m

2; p < 0.001) significantly decreased among male patients at follow-up (

Table 2). No Significant within-group change in HGS was observed in either males or females. According to BIA, males showed significant decreases in body fat percentage (22.2% ± 7.9% vs. 16.4% ± 7.9%; p < 0.001) and skeletal muscle mass (30.0 ± 4.1 kg vs. 28.7 ± 3.98 kg; p < 0.001), whereas females showed significant increases in body fat percentage (34.1% ± 9.0% vs. 23.0% ± 10.3%; p < 0.001) and phase angle (4.7° ± 0.9° vs. 5.1° ± 0.9°; p = 0.002). Regarding the blood test results, significant increases in TLC (1,199.7 ± 643.0 cells/mm

3 vs. 1,518.8 ± 563.3 cells/mm

3; p = 0.001) and albumin (3.4 ± 0.5 g/dL vs. 3.8 ± 0.4 g/dL; p < 0.001) and a significant decrease in CRP (6.3 ± 7.2 mg/dL vs. 3.0 ± 5.3 mg/dL; p = 0.012) were observed in males. In females, the albumin level increased significantly at follow-up (3.3 ± 0.7 g/dL vs. 4.0 ± 0.6 g/dL; p = 0.001). With regard to nutrient intake, caloric intake (1,337.7 ± 565.7 kcal vs. 1,624.1 ± 505.78 kcal; p = 0.020), protein intake (57.1 ± 29.4 g vs. 70.2 ± 29.18 g; p = 0.042), caloric intake percentage (65.3% ± 33.1% vs. 82.6% ± 25.8%; p = 0.008), and protein intake percentage (66.7% ± 36.9% vs. 82.5% ± 34.5%; p = 0.042) significantly increased from baseline to follow-up in males compared with those in females.

Table 2Comparison of baseline and follow-up data by sex

Table 2

|

Patient characteristics |

Male (n = 38, 73.1%) |

Female (n = 14, 26.9%) |

p-value†

|

|

Baseline |

Follow-up |

p value*

|

Baseline |

Follow-up |

p value |

|

Weight (kg) |

71.0 ± 12.6 |

68.5 ± 12.3 |

< 0.001 |

63.5 ± 16.7 |

62.8 ± 16.8 |

0.590 |

0.254 |

|

Body mass index (kg/m2) |

24.0 ± 3.8 |

23.2 ± 3.8 |

< 0.001 |

24.5 ± 5.7 |

24.3 ± 5.8 |

0.618 |

0.259 |

|

HGS (kg) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Right |

29.4 ± 12.2 |

30.0 ± 11.5 |

0.371 |

13.5 ± 7.2 |

14.9 ± 7.8 |

0.166 |

0.962 |

|

Left |

29.5 ± 10.8 |

30.5 ± 10.4 |

0.193 |

13.3 ± 5.2 |

14.7 ± 6.1 |

0.098 |

0.356 |

|

Bioelectrical impedance analysis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Body fat percentage (%) |

22.2 ± 7.9 |

16.4 ± 7.9 |

< 0.001 |

34.1 ± 9.0 |

23.0 ± 10.3 |

< 0.001 |

0.526 |

|

Skeletal muscle mass (kg) |

30.0 ± 4.1 |

28.7 ± 3.9 |

< 0.001 |

21.5 ± 4.6 |

20.5 ± 5.5 |

0.221 |

0.467 |

|

Phase angle (°) |

5.8 ± 0.8 |

5.9 ± 0.8 |

0.167 |

4.7 ± 0.9 |

5.1 ± 0.9 |

0.002 |

0.208 |

|

Blood test |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TLC (cells/mm2; > 2,000)‡

|

1,199.7 ± 643.0 |

1,518.8 ± 563.3 |

0.001 |

1,420.5 ± 782.1 |

1,750.8 ± 499.8 |

0.143 |

0.128 |

|

Albumin (g/dL; 3.5–5.2)‡

|

3.4 ± 0.5 |

3.8 ± 0.4 |

< 0.001 |

3.3 ± 0.7 |

4.0 ± 0.6 |

0.001 |

0.514 |

|

CRP (mg/dL; 0.0–0.5)‡

|

6.3 ± 7.2 |

3.0 ± 5.3 |

0.012 |

6.3 ± 11.1 |

2.1 ± 3.5 |

0.194 |

0.278 |

|

Nutrient intake |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Calories (kcal) |

1,337.7 ± 565.7 |

1,624.1 ± 505.7 |

0.020 |

918.5 ± 455.9 |

1,136.2 ± 364.1 |

0.110 |

0.093 |

|

Protein (g) |

57.1 ± 29.4 |

70.2 ± 29.1 |

0.042 |

46.1 ± 23.6 |

49.2 ± 21.7 |

0.630 |

0.047 |

|

Intake/recommended caloric ratio (%) |

65.3 ± 33.1 |

82.6 ± 25.8 |

0.008 |

57.5 ± 31.7 |

70.4 ± 25.5 |

0.110 |

0.080 |

|

Intake/recommended protein ratio (%) |

66.7 ± 36.9 |

82.5 ± 34.5 |

0.042 |

67.2 ± 40.1 |

71.5 ± 37.2 |

0.617 |

0.039 |

Changes in body composition and other factors according to caloric intake

Table 3 presents the baseline and follow-up values in the ING and HNG.

Table 3Comparison of baseline and follow-up data by caloric intake

Table 3

|

Patient characteristics |

HNG (< 70%; n = 21, 40.4%) |

ING (≥ 70%; n = 31, 59.6%) |

p value†

|

|

Baseline |

Follow-up |

p value*

|

Baseline |

Follow-up |

p value |

|

Weight (kg) |

67.7 ± 16.5 |

66.6 ± 16.2 |

0.206 |

69.9 ± 12.5 |

67.3 ± 12.1 |

0.001 |

0.254 |

|

Body mass index (kg/m2) |

23.9 ± 4.4 |

23.5 ± 4.4 |

0.249 |

24.3 ± 4.4 |

23.4 ± 4.5 |

0.001 |

0.259 |

|

HGS (kg) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Right |

22.7 ± 13.9 |

23.3 ± 13.1 |

0.446 |

26.8 ± 12.5 |

27.8 ± 12.0 |

0.222 |

0.962 |

|

Left |

22.8 ± 14.8 |

22.9 ± 13.4 |

0.958 |

26.6 ± 9.6 |

28.5 ± 10.1 |

0.022 |

0.356 |

|

Bioelectrical impedance analysis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Body fat percentage (%) |

27.3 ± 9.5 |

19.6 ± 8.7 |

< 0.001 |

24.1 ± 9.8 |

17.2 ± 9.2 |

< 0.001 |

0.526 |

|

Skeletal muscle mass (kg) |

26.3 ± 6.5 |

25.0 ± 7.1 |

0.037 |

28.6 ± 4.9 |

27.5 ± 4.3 |

0.001 |

0.467 |

|

Phase angle (°) |

5.3 ± 1.2 |

5.6 ± 1.0 |

0.044 |

5.6 ± 0.8 |

5.8 ± 0.8 |

0.095 |

0.208 |

|

Blood test |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TLC (cells/mm3; > 2,000)‡

|

1,137.6 ± 714.1 |

1,552.8 ± 524.4 |

0.009 |

1,314.4 ± 648.4 |

1,578.1 ± 579.7 |

0.010 |

0.128 |

|

Albumin (g/dL; 3.5–5.2)‡

|

3.3 ± 0.6 |

3.9 ± 0.5 |

< 0.001 |

3.4 ± 0.4 |

3.8 ± 0.4 |

< 0.001 |

0.514 |

|

CRP (mg/dL; 0.0–0.5)‡

|

9.4 ± 10.5 |

3.7 ± 4.9 |

0.014 |

4.5 ± 5.2 |

2.3 ± 5.1 |

0.106 |

0.278 |

|

Nutrient intake |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Calories (kcal) |

1,028.3 ± 427.2 |

1,002.6 ± 299.3 |

0.811 |

1,372.6 ± 613.7 |

1,847.8 ± 307.4 |

0.001 |

0.093 |

|

Protein (g) |

46.4 ± 20.7 |

39.0 ± 15.3 |

0.190 |

59.9 ± 31.7 |

82.9 ± 21.0 |

0.001 |

0.047 |

|

Intake/recommended caloric ratio (%) |

52.6 ± 24.1 |

55.0 ± 14.8 |

0.710 |

70.8 ± 36.0 |

96.7 ± 16.6 |

0.001 |

0.080 |

|

Intake/recommended protein ratio (%) |

58.6 ± 25.9 |

49.5 ± 20.1 |

0.183 |

72.6 ± 43.2 |

100.8 ± 27.0 |

0.001 |

0.039 |

Compared with the baseline values, BMI (24.3 ± 4.4 kg/m2 vs. 23.4 ± 4.5 kg/m2; p = 0.001), body fat percentage (24.1% ± 9.8% vs. 17.2% ± 9.2%; p < 0.001), and skeletal muscle mass (28.6 ± 4.9 kg vs. 27.5 ± 4.3 kg; p = 0.001) significantly decreased in the ING at follow up, whereas left HGS (26.6 ± 9.6 kg vs. 28.5 ± 10.1 kg; p = 0.022), TLC (1,314.4 ± 648.4 cells/mm3 vs. 1,578.1 ± 579.7 cells/mm3; p = 0.010), and albumin (3.4 ± 0.4 g/dL vs. 3.8 ± 0.4 g/dL; p < 0.001) significantly increased in the ING at follow-up.

In the HNG, body composition analysis revealed significant decreases in body fat percentage (27.3% ± 9.5% vs. 19.6% ± 8.7%; p < 0.001) and skeletal muscle mass (26.3 ± 6.5 kg vs. 25.0 ± 7.1 kg; p = 0.037), but a significant increase in phase angle (5.3° ± 1.2° vs. 5.6° ± 1.0°; p = 0.044). In the HNG’s blood test results, TLC (1,137.6 ± 714.1 cells/mm3 vs. 1,552.8 ± 524.4 cells/mm3; p = 0.009) and albumin (3.3 ± 0.6 g/dL vs. 3.9 ± 0.5 g/dL; p < 0.001) significantly increased, while CRP (9.4 ± 10.5 mg/dL vs. 3.7 ± 4.9 mg/dL; p = 0.014) significantly decreased. Other variables did not significantly differ between the ING and HNG, except for the significantly higher protein intake at baseline in the ING (72.6 ± 43.2 → 100.8 ± 27.0% vs. 58.6 ± 25.9 → 49.5 ± 20.1%; p = 0.039).

In the coordinate plane for BIA, the impedance vector represents the sum of R and Xc, which are plotted on the x-axis and y-axis, respectively.

The distribution and shift of bioelectrical impedance vectors, which can be used to determine the total body water content, body type, body composition, and nutritional status [

19], were compared between the ING and HNG after 1 week.

Figure 1 shows the results for individual vectors in BIVA. The vectors of each participant in the ING and HNG were plotted on the 50%, 75%, and 95% tolerance ellipses of a healthy population to determine changes in body composition of these patients recovering from trauma.

Figure 1

Impedance vector distributions of hypocaloric (< 70%) and isocaloric (≥ 70%) nutrition groups.

BIVA, bioelectrical impedance vector analysis; R/Ht, resistance normalized for height; Xc/Ht, reactance normalized for height.

HNG distribution

Vector points representing 21 patients in the HNG were plotted on the Xc-R plane. At baseline, 11 (52%) vectors fell outside the reference 75% tolerance ellipses, compared with only 9 (42%) at the 1-week follow-up. Therefore, 10% of the vector points have moved further into the allowable ellipse.

The vector points were scattered randomly throughout the entire quadrant at baseline, with no clear trend in the directions of the shifts at the 1-week follow-up.

ING distribution

Vector points reflecting 15 (48%) patients from a total of 31 in the ING fell outside the reference 75% tolerance ellipses at baseline, compared with only 8 (25%) at the 1-week follow-up. Thus, 23% vector points moved into tolerance ellipses.

Most of the vector points representing the patients were plotted in the upper-left and lower-left quadrants at baseline. However, at the 1-week follow-up, they moved to the upper-right quadrant.

Changes in body composition and other factors in the HGS-increase and HGS-decrease groups

In the HGS-increase group, right HGS (21.6 ± 10.7 kg vs. 24.8 ± 11.3 kg; p < 0.001), left HGS (22.4 ± 9.7 kg vs. 24.9 ± 10.6 kg; p < 0.001), phase angle (5.5° ± 1.0° vs. 5.7° ± 0.9°; p = 0.028), actual/recommended caloric intake ratio (62.6% ± 32.7% vs. 83.0% ± 24.8%; p = 0.004), and actual/recommended protein intake ratio (66.6% ± 37.4% vs. 84.1% ± 35.7%; p = 0.029) significantly increased from baseline to follow-up (

Table 4). Conversely, body weight (67.0 ± 14.7 kg vs. 65.5 ± 14.2 kg; p < 0.001), BMI (23.9 ± 4.7 kg/m

2 vs. 23.3 ± 4.6 kg/m

2; p < 0.001), body fat percentage (24.0% ± 9.4% vs. 17.5% ± 9.1%; p < 0.001), and skeletal muscle mass (27.4 ± 5.5 kg vs. 26.2 ± 5.2 kg; p < 0.001) decreased significantly at follow-up. In contrast, TLC (1,351.7 ± 689.1 cells/mm

3 vs. 1,633.6 ± 545.2 cells/mm

3; p = 0.007), albumin (3.4 ± 0.5 g/dL vs. 3.9 ± 0.4 g/dL; p < 0.001) increased significantly, whereas CRP (4.7 ± 5.4 mg/dL vs. 1.7 ± 2.3 mg/dL; p = 0.011) decreased from baseline to follow-up.

Table 4Comparison of baseline and follow-up data by HGS changes

Table 4

|

Patient characteristics |

HGS increase group (n = 32, 61.5%) |

HGS decrease group (n = 20, 38.5%) |

p value†

|

|

Baseline |

Follow-up |

p value*

|

Baseline |

Follow-up |

p value |

|

Weight (kg) |

67.0 ± 14.7 |

65.5 ± 14.2 |

< 0.001 |

63.5 ± 16.7 |

62.8 ± 16.8 |

0.590 |

0.252 |

|

Body mass index (kg/m2) |

23.9 ± 4.7 |

23.3 ± 4.6 |

0.042 |

24.6 ± 3.8 |

23.7 ± 4.1 |

0.005 |

0.265 |

|

HGS (kg) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Right |

21.6 ± 10.7 |

24.8 ± 11.3 |

< 0.001 |

30.7 ± 14.8 |

27.8 ± 14.3 |

< 0.001 |

- |

|

Left |

22.4 ± 9.7 |

24.9 ± 10.6 |

< 0.001 |

29.2 ± 14.1 |

28.2 ± 13.4 |

0.242 |

- |

|

Bioelectrical impedance analysis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Body fat percentage (%) |

24.0 ± 9.4 |

17.5 ± 9.1 |

< 0.001 |

27.8 ± 10.0 |

19.3 ± 8.9 |

< 0.001 |

0.113 |

|

Skeletal muscle mass (kg) |

27.4 ± 5.5 |

26.2 ± 5.2 |

< 0.001 |

28.2 ± 6.1 |

27.0 ± 6.5 |

0.049 |

0.763 |

|

Phase angle (°) |

5.5 ± 1.0 |

5.7 ± 0.9 |

0.028 |

5.5 ± 0.9 |

5.8 ± 0.8 |

0.130 |

0.480 |

|

Blood test |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TLC (cells/mm3; > 2,000)‡

|

1,351.7 ± 689.1 |

1,633.6 ± 545.2 |

0.007 |

1,077.0 ± 624.5 |

1,462.8 ± 566.5 |

0.014 |

0.304 |

|

Albumin (g/dL; 3.5–5.2)‡

|

3.4 ± 0.5 |

3.9 ± 0.4 |

< 0.001 |

3.4 ± 0.6 |

3.6 ± 0.5 |

0.005 |

0.206 |

|

CRP (mg/dL; 0.0–0.5)‡

|

4.7 ± 5.4 |

1.7 ± 2.3 |

0.011 |

8.5 ± 10.1 |

4.2 ± 7.1 |

0.082 |

0.838 |

|

Nutrient intake |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Calories (kcal) |

1,224.1 ± 525.2 |

1,548.7 ± 514.1 |

0.010 |

1,242.2 ± 644.7 |

1,417.3 ± 524.9 |

0.272 |

0.254 |

|

Protein (g) |

53.5 ± 27.0 |

67.3 ± 29.3 |

0.031 |

55.8 ± 31.0 |

60.8 ± 28.2 |

0.549 |

0.283 |

|

Intake/recommended calorie ratio (%) |

62.6 ± 32.7 |

83.0 ± 24.8 |

0.004 |

64.6 ± 33.3 |

73.5 ± 27.6 |

0.250 |

0.236 |

|

Intake/recommended protein ratio (%) |

66.6 ± 37.4 |

84.1 ± 35.7 |

0.029 |

67.1 ± 38.4 |

72.4 ± 33.9 |

0.593 |

0.312 |

In the HGS-decrease group, BMI (24.6 ± 3.8 kg/m2 vs. 23.7 ± 4.1 kg/m2; p = 0.005), right HGS (30.7 ± 14.8 kg vs. 27.8 ± 14.3 kg; p < 0.001), body fat percentage (27.8% ± 10.0% vs. 19.3% ± 8.9%; p < 0.001), and skeletal muscle mass (28.2 ± 6.1 kg vs. 27.0 ± 6.5 kg; p = 0.049) significantly decreased from baseline to follow-up. Furthermore, the blood test results of this group showed that from baseline to follow-up, TLC (1,077.0 ± 624.5 cells/mm3 vs. 1,462.8 ± 566.5 cells/mm3; p = 0.014) and albumin (3.4 ± 0.6 g/dL vs. 3.6 ± 0.5 g/dL; p = 0.005) significantly increased, whereas CRP (8.5 ± 10.1 mg/dL vs. 4.2 ± 7.1 mg/dL; p = 0.082) showed no significant change.

Correlations among factors

Differences in actual/recommended protein intake ratio by age were determined by subtracting the baseline from the follow-up value (

Table 5). The differences between the actual/recommended protein intake ratio (r = −0.274, p < 0.05) and right HGS (r = −0.290, p < 0.05) negatively correlated with age. However, the difference in the APACHE II score (r = 0.361, p < 0.05) positively correlated with age. Therefore, protein intake and right HGS may have increased less in older patients.

Table 5Correlations between studied factors associated with HGS change

Table 5

|

Variables |

Mean ± SD |

Protein intake diff (%) |

Caloric intake diff (%) |

PhA diff (°) |

SMM diff (kg) |

Body fat percentage diff (%) |

Lt_HGS diff (kg) |

Rt_HGS diff (kg) |

ISS (score) |

APACHE II (score) |

ICU_LOS (days) |

HOD (days) |

Weight diff (kg) |

Age (yr) |

|

Age (yr) |

53.7 ± 16.7 |

−0.274*

|

−0.179 |

0.180 |

−0.027 |

−0.167 |

0.077 |

−0.290*

|

−0.197 |

0.361*

|

0.055 |

−0.030 |

−0.018 |

1.000 |

|

Weight diff (kg) |

−2.0 ± 3.9 |

−0.108 |

−0.157 |

0.098 |

0.308*

|

0.400**

|

0.105 |

0.176 |

−0.326*

|

−0.351*

|

−0.225 |

−0.189 |

1.000 |

|

|

HOD (days) |

21.0 ± 12.8 |

−0.291*

|

−0.252 |

−0.065 |

−0.478**

|

−0.090 |

0.005 |

−0.209 |

0.232 |

0.172 |

0.188 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

ICU_LOS (days) |

3.3 ± 2.6 |

−0.122 |

−0.112 |

−0.176 |

−0.135 |

0.023 |

0.145 |

0.022 |

0.326*

|

0.015 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

APACHE II (score) |

7.7 ± 5.0 |

−0.391*

|

−0.407*

|

−0.171 |

0.167 |

−0.496**

|

−0.254 |

−0.236 |

−0.003 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

ISS (score) |

19.4 ± 8.7 |

0.177 |

0.278 |

0.183 |

−0.352*

|

−0.031 |

0.130 |

0.215 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rt_HGS diff (kg) |

0.8 ± 4.1 |

0.114 |

0.073 |

−0.119 |

−0.049 |

0.174 |

0.528**

|

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lt_HGS diff (kg) |

1.1 ± 4.2 |

0.083 |

0.095 |

0.002 |

−0.189 |

0.207 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Body fat percentage diff (%) |

−7.2 ± 6.0 |

0.207 |

0.145 |

0.059 |

−0.327*

|

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SMM diff (kg) |

−1.2 ± 2.1 |

−0.063 |

−0.128 |

−0.115 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PhA diff (°) |

0.2 ± 0.6 |

−0.029 |

0.098 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Caloric intake diff (%) |

16.2 ± 35.4 |

0.900**

|

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Protein intake diff (%) |

12.7 ± 42.4 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The difference in body weight positively correlated with the differences in skeletal muscle mass (r = 0.308, p < 0.05) and body fat percentage (r = 0.400, p < 0.01) but negatively correlated with ISS (r = −0.326, p < 0.05) and the APACHE II score (r = −0.351, p < 0.05). Regarding the length of hospital stay, negative correlations were observed with the differences in actual/recommended protein intake ratio (r = −0.291, p < 0.05) and skeletal muscle mass (r = −0.478, p < 0.01). The length of ICU stay positively correlated with ISS (r = 0.326, p < 0.05). In addition, the APACHE II score negatively correlated with the differences in actual/recommended protein intake ratio (r = −0.391, p < 0.05), actual/recommended caloric intake ratio (r = −0.407, p < 0.05), and body fat percentage (r = −0.496, p < 0.01). ISS also negatively correlated with the difference in skeletal muscle mass (r = −0.352, p < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

In this study, patients recovering from trauma were mostly young males with high- to medium-intensity occupations. Most of these trauma cases were caused by blunt injury, such as falls or motor vehicle accidents [

20]. Patients with trauma need to rapidly return to their previous social and economic activities. Recovery can be achieved through proper treatment and rehabilitation. Normally, such patients have a good nutritional status upon admission, but as the length of hospital stay increases, they often develop malnutrition. Indeed, nutritional assessment indicated that the majority of patients in this study were well nourished at baseline.

The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017 showed that HGS was lowest in men and women aged 50–54 years (≤ 35.3 and ≤ 19.2 kg) [

21]. Guerra et al. [

22] reported that the HGS in 688 inpatients was 34.0 and 20.0 kg for men and women in the well-nourished group, 28.0 and 14.6 kg in the moderately malnourished group, and 30.0 and 14.0 kg in the suspected malnutrition group, respectively. The patients in this study showed a high degree of muscle loss during hospitalization, with reductions in skeletal muscle mass of 1.3 kg/week for men and 1.0 kg/week for women. However, HGS, as an index of muscle quality, increased from 29.4 and 13.5 kg in men and women at baseline to 30.0 and 14.9 kg at follow-up, respectively, although these differences were not significant.

In the body composition analysis, the body fat percentage markedly decreased in both sexes during the ICU stay, even after only 1 week. Their muscle mass also decreased, with statistically significant reductions in men. Delayed recovery from trauma is associated with confinement to bed and accelerated muscle loss, making it as the main cause of physical activity limitations for affected patients [

23]. Meyer et al. [

24] reported that low muscle strength increased susceptibility to various types of damage, undermining recovery from acute diseases, injury, and surgery.

The HGS-decrease group had a higher baseline value than the HGS-increase group (30.7 kg vs. 21.6 kg). This finding may be explained by the significant decreases in body fat percentage and skeletal muscle mass but with significant increases in the phase angle and dietary intake in the HGS-increase group. In the HGS-decrease group, body fat percentage, muscle mass, and HGS significantly decreased from baseline and to the 1-week follow-up, while phase angle and oral intake increased, although the changes were not significant. Norman et al. [

25] reported that muscle function responds earlier to both nutritional deficiencies and non-nutritional intake than body composition variables, such as muscle and body mass, and that muscle mass loss is not entirely responsible for muscle dysfunction in malnutrition cases. In some patients with trauma, the nutritional status deteriorates during hospitalization, resulting in malnutrition. Therefore, proper evaluation and improvement of nutritional intake are crucial. Early identification of malnutrition caused by deficient nutritional intake can improve short- and long-term clinical outcomes [

26]. In the present study, left HGS increased significantly after 1 week in the ING that received ≥ 70% of the recommended caloric intake.

HGS reflects malnutrition before any clear changes in body composition [

25]. In the present study’s body composition analysis, the phase angle tended to increase in both groups and increased significantly in the nutrition group that received < 70% of the recommended caloric intake. Caccialanza et al. [

27] suggested that the significant correlations of phase angle and HGS changes with energy intake indicate that effective nutritional interventions can improve body function. Reis et al. [

28] suggested that phase angle positively correlates with HGS in hospitalized patients. Phase angle can be used as an index of muscle strength and muscle mass and may predict the length of hospital stay and mortality risk. de Blasio et al. [

29] measured the BIA variables and HGS of 237 patients with COPD and showed that phase angle and the BIA index were independent predictors of HGS and respiratory muscle strength.

In the present study, the impedance vectors often moved to the reference 75% ellipse in both the HNG and ING after 1 week, with the phase angle subsequently increased. However, the shift toward the reference 75% ellipse was greater in the ING than in the HNG. Adequate nutritional support during the recovery process can help restore normal body composition. In patients with chronic diseases, nutritional interventions often lead to a shift of the BIVA vector within the reference ellipse.

Furthermore, the difference in actual/recommended protein intake ratio and right HGS increase showed negative correlations with age. Aging is a major factor in muscle loss. In this study, the levels of HGS, muscle strength, and physical activity were evaluated as muscle function indicators. Among them, HGS could predict the clinical outcome of patients with weakened lower limb muscles [

30].

This study has some limitations. First, it could not evaluate nutritional supply throughout the entire hospitalization period, considering that the 24-hour recall method was used only during oral intake. The analysis merely relied on the nutrition supply data provided immediately before the baseline and follow-up assessments. Second, the amounts of calories provided at baseline significantly varied, given that this was not a randomized control trial that controls for dietary caloric and protein intakes. The caloric demands were calculated using a formula; thus, the accuracy may demonstrate some limitations compared with that of methods using an indirect calorimeter. Early nutritional supply is associated with HGS and phase angle improvements; however, considering the characteristics of patients with trauma confined to bed for long periods, evaluating the strength of the lower extremities may be necessary. HGS alone should not be used to evaluate the overall body strength. Moreover, the total sample size was small, with men accounting for the majority; thus, the BIVA graph could not appropriately differentiate patients according to sex.

In patients with trauma, changes in body composition and muscle strength result from excessive metabolism caused by trauma and surgery, insufficient nutritional supply, the injury itself, and activity restrictions due to long-term hospitalization. In the current study, 2 consecutive measurements of HGS and muscle mass showed that muscle loss in patients with trauma was severe even after only 1 week, but if nutritional intake was sufficient, HGS could increase. For effective treatment, both quantitative and qualitative changes in the muscle must be evaluated as early as possible, along with sufficient nutrition support. Protein supply, rehabilitation treatment, and exercise all help prevent sarcopenia and enhance the clinical treatment effects.

CONCLUSION

The study results suggest that although quantitative muscle loss occurs during trauma recovery, appropriate nutritional support can mitigate qualitative muscle deterioration, thereby preserving the muscle’s composition and functional capacity.

NOTES

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

-

Author Contributions:

Conceptualization:Lee JH, Kwon J, Park YK.

Data curation:Lee JH, Kwon S, Yang S, Choi D.

Formal analysis:Lee JH, Kwon S, Yang S, Choi D.

Investigation:Kwon J, Park YK.

Writing - original draft:Lee JH, Kwon S, Yang S, Choi D, Kwon J, Park YK.

Writing - review & editing:Lee JH, Kwon S, Yang S, Choi D, Kwon J, Park YK.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cerra FB. Hypermetabolism, organ failure, and metabolic support. Surgery 1987;101:1-14.

- 2. Monk DN, Plank LD, Franch-Arcas G, Finn PJ, Streat SJ, et al. Sequential changes in the metabolic response in critically injured patients during the first 25 days after blunt trauma. Ann Surg 1996;223:395-405.

- 3. Peng S, Plank LD, McCall JL, Gillanders LK, McIlroy K, et al. Body composition, muscle function, and energy expenditure in patients with liver cirrhosis: a comprehensive study. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;85:1257-1266.

- 4. Windsor JA, Hill GL. Grip strength: a measure of the proportion of protein loss in surgical patients. Br J Surg 1988;75:880-882.

- 5. White JV, Guenter P, Jensen G, Malone A, Schofield M, et al. Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition). J Acad Nutr Diet 2012;112:730-738.

- 6. Rantanen T, Guralnik JM, Foley D, Masaki K, Leveille S, et al. Midlife hand grip strength as a predictor of old age disability. JAMA 1999;281:558-560.

- 7. Sayer AA, Dennison EM, Syddall HE, Gilbody HJ, Phillips DI, et al. Type 2 diabetes, muscle strength, and impaired physical function: the tip of the iceberg? Diabetes Care 2005;28:2541-2542.

- 8. Rantanen T, Harris T, Leveille SG, Visser M, Foley D, et al. Muscle strength and body mass index as long-term predictors of mortality in initially healthy men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2000;55:M168-M173.

- 9. Kerr A, Syddall HE, Cooper C, Turner GF, Briggs RS, et al. Does admission grip strength predict length of stay in hospitalised older patients? Age Ageing 2006;35:82-84.

- 10. Mohamed-Hussein AAR, Makhlouf HA, Selim ZI, Gamaleldin Saleh W. Association between hand grip strength with weaning and intensive care outcomes in COPD patients: a pilot study. Clin Respir J 2018;12:2475-2479.

- 11. Bahat G, Tufan A, Ozkaya H, Tufan F, Akpinar TS, et al. Relation between hand grip strength, respiratory muscle strength and spirometric measures in male nursing home residents. Aging Male 2014;17:136-140.

- 12. Gubelmann C, Vollenweider P, Marques-Vidal P. Association of grip strength with cardiovascular risk markers. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2017;24:514-521.

- 13. Kimbro LB, Mangione CM, Steers WN, Duru OK, McEwen L, et al. Depression and all-cause mortality in persons with diabetes mellitus: are older adults at higher risk? Results from the Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:1017-1022.

- 14. Kawamoto R, Ninomiya D, Kasai Y, Kusunoki T, Ohtsuka N, et al. Handgrip strength is associated with metabolic syndrome among middle-aged and elderly community-dwelling persons. Clin Exp Hypertens 2016;38:245-251.

- 15. Verlaan S, Van Ancum JM, Pierik VD, Van Wijngaarden JP, Scheerman K, et al. Muscle measures and nutritional status at hospital admission predict survival and independent living of older patients-the EMPOWER study. J Frailty Aging 2017;6:161-166.

- 16. Kim SW, Lee HA, Cho EH. Low handgrip strength is associated with low bone mineral density and fragility fractures in postmenopausal healthy Korean women. J Korean Med Sci 2012;27:744-747.

- 17. McClave SA, Taylor BE, Martindale RG, Warren MM, Johnson DR, et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2016;40:159-211.

- 18. Singer P, Blaser AR, Berger MM, Alhazzani W, Calder PC, et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clin Nutr 2019;38:48-79.

- 19. Piccoli A, Rossi B, Pillon L, Bucciante G. A new method for monitoring body fluid variation by bioimpedance analysis: the RXc graph. Kidney Int 1994;46:534-539.

- 20. Byun CS, Park IH, Oh JH, Bae KS, Lee KH, et al. Epidemiology of trauma patients and analysis of 268 mortality cases: trends of a single center in Korea. Yonsei Med J 2015;56:220-226.

- 21. An KY. Physical activity level in Korean adults: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017. Epidemiol Health 2019;41:e2019047.

- 22. Guerra RS, Fonseca I, Pichel F, Restivo MT, Amaral TF. Handgrip strength and associated factors in hospitalized patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2015;39:322-330.

- 23. Rantanen T, Volpato S, Ferrucci L, Heikkinen E, Fried LP, et al. Handgrip strength and cause-specific and total mortality in older disabled women: exploring the mechanism. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:636-641.

- 24. Meyer HE, Tverdal A, Falch JA, Pedersen JI. Factors associated with mortality after hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 2000;11:228-232.

- 25. Norman K, Stobäus N, Gonzalez MC, Schulzke JD, Pirlich M. Hand grip strength: outcome predictor and marker of nutritional status. Clin Nutr 2011;30:135-142.

- 26. Sorensen J, Kondrup J, Prokopowicz J, Schiesser M, Krähenbühl L, et al. EuroOOPS: an international, multicentre study to implement nutritional risk screening and evaluate clinical outcome. Clin Nutr 2008;27:340-349.

- 27. Caccialanza R, Cereda E, Klersy C, Bonardi C, Cappello S, et al. Phase angle and handgrip strength are sensitive early markers of energy intake in hypophagic, non-surgical patients at nutritional risk, with contraindications to enteral nutrition. Nutrients 2015;7:1828-1840.

- 28. Reis BC, de Branco F, Pessoa DF, Barbosa CD, dos Reis AS, et al. Phase angle is positively associated with handgrip strength in hospitalized individuals. Topics Clin Nutr 2018;33:127-133.

- 29. de Blasio F, Santaniello MG, de Blasio F, Mazzarella G, Bianco A, et al. Raw BIA variables are predictors of muscle strength in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur J Clin Nutr 2017;71:1336-1340.

- 30. Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, Boirie Y, Cederholm T, et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing 2010;39:412-423.