ABSTRACT

Pressure injuries are common complications in patients with limited mobility, particularly those who are bedridden. These wounds not only cause pain and reduce quality of life but also lead to prolonged hospitalization, increased risk of infection, and higher healthcare costs. Among the various contributing factors, malnutrition plays a crucial role by impairing collagen synthesis, weakening immune function, and delaying tissue repair. Adequate nutritional support—particularly sufficient protein and energy intake—is therefore an essential component of comprehensive pressure injury management. We present the case of a paraplegic patient who developed a vulvar pressure injury. A structured, stepwise nutritional intervention was implemented, including adjustment of meal composition based on appetite, supplementation with high-protein oral nutritional supplements, vitamins and minerals, and the use of probiotics to manage diarrhea. As a result, the patient’s daily protein intake increased from less than 10 g to 80–90 g, accompanied by progressive wound improvement. Serial clinical assessments showed reduced slough, increased granulation tissue formation, and epithelialization. This case highlights the vital role of individualized nutritional management within a multidisciplinary approach to pressure injury care. Stepwise nutritional intervention, tailored to the patient’s tolerance and clinical status, contributed significantly to wound healing. Nutritional optimization should be considered an integral component of effective pressure injury treatment strategies.

-

Keywords: Pressure injury; Wound; Wound healing; Nutrition therapy

INTRODUCTION

Pressure injuries result from sustained pressure—often due to an individual’s body weight or a medical device—exceeding the tolerance threshold of the skin and underlying tissues over time. Several factors contribute to their development, including elevated arteriole pressure, shearing forces, friction, moisture, and poor nutritional status. The incidence of pressure injuries varies across clinical settings. For example, their prevalence among hospitalized patients ranges from 5% to 15%, with significantly higher rates reported in long-term care facilities and intensive care units [

1].

Nutrition plays a critical role in both the prevention and management of pressure injuries. Adequate nutritional support promotes wound healing by supporting collagen synthesis, maintaining immune function, and facilitating tissue repair. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in hospitalized patients at high risk for pressure injury found that nutritional support could save approximately $425 per patient [

2].

According to the 2025 National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP) guidelines, nutritional supplementation should be initiated for individuals at risk of pressure injuries who are malnourished or unable to meet their nutritional requirements through regular dietary intake. These guidelines emphasize the importance of sufficient protein intake to achieve a positive nitrogen balance in adults vulnerable to pressure injuries. Additionally, carbohydrate-based energy and micronutrient supplementation—particularly vitamin C and zinc—is recommended for those with confirmed malnutrition or documented micronutrient deficiencies and should be provided alongside adequate protein intake to ensure comprehensive nutritional support [

3].

The 2019 NPIAP guidelines further recommend providing 1.25–1.5 g of protein per kilogram of body weight per day for adults with pressure injuries who are malnourished or at risk of malnutrition. For individuals with Category/Stage II or more severe pressure injuries, providing high-calorie, high-protein oral nutritional supplements or enteral formulas enriched with arginine, zinc, and antioxidants is advised [

4]. However, most studies on pressure injury prevention and treatment remain small in scale, with limited data availability, and published case reports are relatively few. Therefore, this report describes a paraplegic patient with a vulvar pressure injury who achieved notable wound healing through structured nutritional support. This case report aims to contribute to the growing evidence base highlighting the effectiveness of nutritional intervention in pressure injury management.

CASE

A 54-year-old paraplegic woman (height 155 cm, weight 55 kg, body mass index 22.9 kg/m2) had a history of repeated hospital admissions due to recurrent vulvar wounds and pressure injuries. She was in a state of nutritional imbalance caused by limited mobility, poor appetite due to selective eating habits, and frequent meal skipping associated with a depressive mood.

In February 2025, only one month after discharge, she was readmitted with worsening of the vulvar wound, increased exudate, and fever. On February 14, clinical examination revealed extensive slough covering the underlying granulation tissue, with a sinus tract measuring more than 7 cm in depth. Her oral intake was < 400 kcal/day and < 10 g protein/day, indicating severe malnutrition. Initial laboratory results were as follows: blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 9 mg/dL, creatinine 0.56 mg/dL, BUN/Cr ratio 16:1, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein 2.3 mg/dL.

The patient received an individualized nutritional care plan, including supplementation with vitamin C (1,000 mg/tablet) and a multivitamin and mineral preparation containing vitamin A (2,500 IU), vitamin C (150 mg), zinc (11 mg), and selenium (55 μg). Additional interventions included dietary adjustments, high-protein oral supplements, and probiotics to manage antibiotic-associated diarrhea.

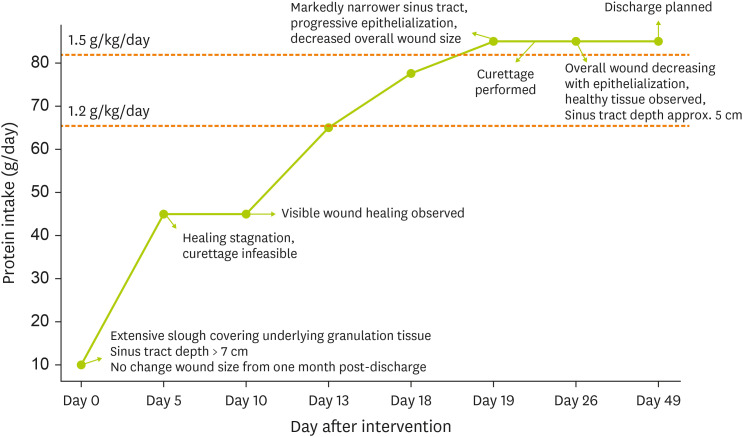

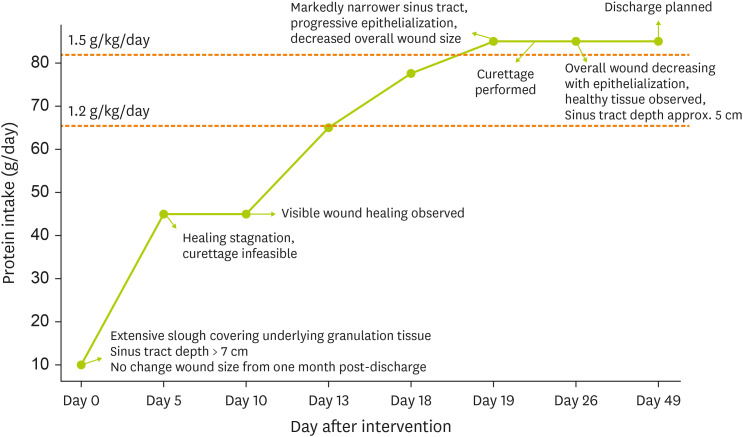

With regular follow-up and stepwise management, her caloric and protein intake increased progressively, reaching approximately 45 g/day by late February, 70 g/day by early March, and up to 90 g/day by mid-March. Concurrently, wound assessments demonstrated marked improvement: reduction of slough, development of healthy granulation tissue, narrowing of the sinus tract (depth decreased to 5 cm), and progressive contraction of wound margins, resulting in a notable reduction in overall wound size (

Table 1,

Figures 1 and

2). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Seoul Metropolitan Government-Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center (IRB No. 30-2025-47).

Table 1 Stepwise nutritional support and wound healing progression

Table 1

|

Date |

Daily nutritional intake |

BUN/Cr ratio |

Wound status |

Nutritional intervention |

|

Feb. 14 |

< 400 kcal, < 10 g protein |

16:1 |

Dark pink granulation with slough; Sinus tract: > 7 cm |

Diet modification with high-protein ONS, vitamin C 1,000 mg/day, multivitamin and mineral supplement |

|

Feb. 19 |

900 kcal, 45 g protein |

36:1 |

Chronic wound with slough; Sinus tract: > 7 cm |

Adding probiotics (Saccharomyces boulardii) to improve diarrhea |

|

Feb. 24 |

900 kcal, 45 g protein |

36:1 |

Reduction in wound size; Depth of the sinus tract remains similar; Ischial bone is palpable |

|

|

Feb. 27 |

1,100–1,200 kcal, 65 g protein |

|

Granulation increased; slough decreased |

Adjusting ONS to improve compliance |

|

Mar. 4 |

1,200–1,300 kcal, 75–80 g protein |

33:1 |

Reduction in slough tissue and increase in granulation tissue; Wound diameter markedly narrowed; Epithelialization; Overall wound size decreased; Tunnel end palpable at ~7 cm |

|

|

Mar. 5–7 |

1,600 kcal, 80–90 g protein |

34:1 |

Curettage feasible, performed by PS |

|

Mar. 12

Discharge planned Apr. 4 |

|

|

Significant wound healing; Healthy granulation tissue; Epithelialization; Sinus tract: approximately 5 cm |

|

Figure 1 Relationship between protein intake and wound healing over time.

Figure 2 Wound healing progression over time.

DISCUSSION

This case highlights several critical aspects of nutrition in wound and pressure injury management. First, severe malnutrition, with protein intake below 10 g/day, was associated with delayed wound healing. Once protein intake was gradually increased to approximately 1.2–1.5 g/kg/day, along with supplementation of vitamins and trace elements such as vitamin C and zinc, marked clinical improvement was observed. The proliferation and maturation phases of wound healing are reported to last about 12 days, which, in our case, coincided with a notable rise in protein intake and visible wound healing [

5]. This finding aligns with previous studies demonstrating that supplementation with protein, vitamin C, zinc, and selenium promotes pressure injury healing [

6,

7,

8,

9].

Second, improving nutrient absorption and tolerance is as important as increasing intake. Malabsorption, if unaddressed, can hinder the efficacy of nutritional intervention. In critically ill patients, stool output exceeding 250 g per day indicates substantial energy losses [

10], and excessive stool output can result in significant zinc depletion—estimated at 17.1 mg per kg of feces [

11]. Similar nutrient losses likely occur for other micronutrients. In this case, the patient was initially unable to tolerate high-protein oral nutrition supplement due to antibiotic-associated diarrhea. However, the addition of probiotics effectively reduced diarrhea, improving supplement tolerance and overall intake. Therefore, the goal of nutritional intervention should not only focus on increasing intake but also on correcting absorptive losses to enhance nutritional recovery. Third, wound healing in this patient was achieved through a multidisciplinary approach involving dietitians, physicians, wound care nurses, and psychiatric consultation. This collaboration ensured that both medical and psychosocial factors contributing to malnutrition were addressed.

Wound healing proceeds through four phases—hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling [

12]. Malnutrition disrupts this process by prolonging inflammation, impairing fibroblast proliferation, angiogenesis, and collagen deposition, thereby reducing tensile strength and increasing infection risk [

13,

14]. Protein deficiency, in particular, delays wound repair, raises the risk of wound dehiscence, and is strongly associated with poor healing outcomes [

9].

Vitamin C plays an important role in collagen synthesis during the remodeling phase. For mild wounds (stage I–II) or in cases of vitamin C deficiency, 100–200 mg/day is recommended, whereas severe wounds (stage III–IV pressure injuries or major trauma) may require 1,000–2,000 mg/day until healing is achieved. High doses can promote recovery in severe wounds and burns, though caution is needed in patients prone to nephrolithiasis [

8].

Zinc contributes to protein synthesis, collagen accumulation and epithelialization, making supplementation beneficial in deficient states [

15]. Other nutrients, including arginine, vitamins A and E, selenium, copper, and iron, have also been shown to facilitate wound healing [

5,

16,

17,

18,

19]. The final stage of wound healing may extend up to two years. However, tensile strength typically recovers to only approximately 50% of its original level and rarely exceeds 80% in the long term. Therefore, even after visible healing, maintaining adequate nutrition and periodic follow-up are essential to ensure sustained recovery and minimize complications [

14].

Many studies have evaluated the effect of oral nutritional supplements on pressure injury healing. A meta-analysis demonstrated that in older adults, postoperative, and long-term care patients at risk of pressure injury, providing oral nutritional supplements (250–500 kcal per serving) for 2 to 26 weeks significantly reduced the incidence of new pressure injuries compared with standard care [

20].

A Cochrane review also reported that protein and micronutrient supplementation may increase the number of healed pressure injuries, although the certainty of evidence remains low. Arginine, zinc, and antioxidant nutrients showed a trend toward reducing wound size, but definitive effects on healing rates were not confirmed [

21]. However, most studies were limited by small sample sizes, short follow-up periods, and methodological weaknesses, underscoring the need for larger, well-designed randomized controlled trials to clarify the effects of nutritional interventions on pressure injury healing.

Taken together, this case underscores the central role of individualized nutritional intervention in the recovery of patients with pressure injuries. Clinical improvement was achieved through stepwise protein-energy supplementation, targeted micronutrient support, and management of malabsorption. These findings not only reinforce current guideline recommendations but also highlight the necessity of patient-specific nutritional management that considers comorbidities, medications, laboratory results, and appetite status within a multidisciplinary care framework. Continuous evaluation and timely adjustment of nutritional status are indispensable to maintain recovery and optimize long-term outcomes.

This case demonstrates that nutritional intervention played a decisive role in the healing of a vulvar pressure injury in a paraplegic patient. Structured protein-energy supplementation and improved gastrointestinal tolerance enabled consistent intake, promoting granulation and epithelialization. Inclusion of dietitians in the multidisciplinary care team is therefore essential, and nutritional optimization should be regarded as a core component of pressure injury treatment strategies. Since this is a single case report, definitive conclusions about the efficacy of nutritional intervention cannot be drawn. Further prospective, multicenter studies are warranted to validate these findings and strengthen the evidence base for nutrition-focused wound care.

NOTES

-

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

-

Author Contributions:

Conceptualization: Kim YR.

Data curation: Kim YR.

Formal analysis: Kim YR.

Investigation: Kim YR.

Methodology: Kim YR.

Project administration: Kim YR.

Resources: Kim YR.

Supervision: Park JH.

Validation: Kim YR, Park JH.

Visualization: Kim YR.

Writing - original draft: Kim YR.

Writing - review & editing: Kim YR, Jang MY, Park JH.

REFERENCES

- 1. Mervis JS, Phillips TJ. Pressure ulcers: pathophysiology, epidemiology, risk factors, and presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;81:881-890.

- 2. Tuffaha HW, Roberts S, Chaboyer W, Gordon LG, Scuffham PA. Cost-effectiveness analysis of nutritional support for the prevention of pressure ulcers in high-risk hospitalized patients. Adv Skin Wound Care 2016;29:261-267.

- 3. National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP). European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP). Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance (PPPIA). Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers/injuries: the international guideline. 4th ed. Osborne Park: NPIAP/EPUAP/PPPIA; 2025.

- 4. National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP). European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP). Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance (PPPIA). Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers/injuries: the international guideline. 3rd ed. Osborne Park: NPIAP/EPUAP/PPPIA; 2019.

- 5. Campos AC, Groth AK, Branco AB. Assessment and nutritional aspects of wound healing. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2008;11:281-288.

- 6. Woo HY, Oh SY, Lim L, Im H, Lee H, et al. Efficacy of nutritional support protocol for patients with pressure ulcer: comparison of before and after the protocol. Nutrition 2022;99-100:111638.

- 7. Díaz Leyva de Oliveira K, Haack A, Fortes RC. Nutritional therapy in the treatment of pressure injuries: a systematic review. Rev Bras Geriatr Gerontol 2017;20:562-570.

- 8. Saghaleini SH, Dehghan K, Shadvar K, Sanaie S, Mahmoodpoor A, et al. Pressure ulcer and nutrition. Indian J Crit Care Med 2018;22:283-289.

- 9. Grada A, Phillips TJ. Nutrition and cutaneous wound healing. Clin Dermatol 2022;40:103-113.

- 10. Strack van Schijndel RJM, Wierdsma NJ, van Heijningen EM, Weijs PJ, de Groot SD, et al. Fecal energy losses in enterally fed intensive care patients: an explorative study using bomb calorimetry. Clin Nutr 2006;25:758-764.

- 11. Cox J, Rasmussen L. Enteral nutrition in the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers in adult critical care patients. Crit Care Nurse 2014;34:15-27.

- 12. Spear M. Acute or chronic? What’s the difference? Plast Surg Nurs 2013;33:98-100.

- 13. Ruberg RL. Role of nutrition in wound healing. Surg Clin North Am 1984;64:705-714.

- 14. Singh S, Young A, McNaught C. The physiology of wound healing. Surgery 2017;35:473-477.

- 15. Lansdown AB, Mirastschijski U, Stubbs N, Scanlon E, Agren MS. Zinc in wound healing: theoretical, experimental, and clinical aspects. Wound Repair Regen 2007;15:2-16.

- 16. Thompson C, Fuhrman MP. Nutrients and wound healing: still searching for the magic bullet. Nutr Clin Pract 2005;20:331-347.

- 17. Posthauer ME. The role of nutrition in wound care. Adv Skin Wound Care 2006;19:43-52.

- 18. Stechmiller JK, Childress B, Cowan L. Arginine supplementation and wound healing. Nutr Clin Pract 2005;20:52-61.

- 19. Ju M, Kim Y, Seo KW. Role of nutrition in wound healing and nutritional recommendations for promotion of wound healing: a narrative review. Ann Clin Nutr Metab 2023;15:67-71.

- 20. Stratton RJ, Ek AC, Engfer M, Moore Z, Rigby P, et al. Enteral nutritional support in prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev 2005;4:422-450.

- 21. Langer G, Wan CS, Fink A, Schwingshackl L, Schoberer D. Nutritional interventions for preventing and treating pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2024;2:CD003216.