ABSTRACT

The Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) diet is a brain-focused dietary pattern designed to prevent cognitive decline in older adults. This systematic review, conducted in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines, aimed to examine the association between the MIND diet and cognitive function in older adults. Relevant studies published between 2015 and 2024 were identified through comprehensive searches of PubMed and the Cochrane Library using keywords including “MIND diet,” “cognitive performance,” and “older adults.” From a total of 138 records screened, 11 studies met the inclusion criteria after excluding reviews, meta-analyses, editorials, and those incorporating other lifestyle interventions such as physical activity or education. These studies included 7 prospective cohort studies, 2 cross-sectional studies, 1 randomized controlled trial (RCT), and 1 case-control study, comprising a total of 17,201 participants aged 57–91 years. Across studies, at least 57% of participants were women, and in the 5 studies reporting race, more than 75% were White. Dietary intake and MIND adherence were assessed primarily via food frequency questionnaires, while cognitive outcomes were evaluated using validated instruments including the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, global cognition scores, Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease tests, and magnetic resonance imaging. Six cohort and two cross-sectional studies reported significant associations between higher MIND adherence and better cognitive outcomes. One cohort study and the single RCT showed no effect. Excluding 2 studies with short durations (≤ 3 years), the remaining nine studies suggest consistent cognitive benefits of MIND adherence. Future studies should include systematic reviews and large-scale RCTs focusing on Asian populations.

-

Keywords: Aged; Cognition; Diet, Mediterranean, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension

INTRODUCTION

Dementia not only severely diminishes the quality of life but also imposes a considerable economic burden on families and society. Between 2020 and 2050, the global economic burden related to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other dementias is projected to reach 14.513 trillion international dollars across 152 countries [

1].

The global population is aging rapidly. According to the World Health Organization, one in six people will be ≥ 60 years old by 2030, and the global older adult population is expected to reach 2.1 billion by 2050 [

2]. South Korea is not exempted from this trend. As of 2024, individuals aged ≥ 65 years account for 19.2% of the total population. This proportion is projected to surpass 30% by 2036 and 40% by 2050 [

3]. Moreover, the estimated prevalence of dementia among Koreans aged ≥ 65 years was 9.15%. The number of people with dementia is projected to increase sharply, reaching approximately 3 million by 2050. These demographic shifts contribute to various aging-related health issues, particularly the rising rates of cognitive decline and dementia [

4].

Given this context, developing effective strategies to prevent or delay the onset of dementia has become a major public health priority. Among these strategies, dietary modification to reduce risk factors of dementia is gaining attention as practical and cost-effective [

5]. Many recent studies of various designs have examined the association of dietary factors with cognitive function. For instance, a cohort study conducted in Norway found that a higher intake of fish and fish products, particularly unprocessed fatty fish, was strongly associated with improved cognitive function in older adults [

6]. Moreover, a cross-sectional study involving older Japanese adults found that a diet focused on “plant-based foods and fish,” including vegetables, legumes, seafood, seaweed, fruits, and green tea, was significantly associated with improved cognitive function [

7]. A randomized controlled trial (RCT) indicated that daily consumption of 100% orange juice containing high concentrations of flavanones for 8 weeks significantly improved cognitive function compared with the control diet; thus, certain bioactive dietary compounds may influence cognitive health [

8]. These outcomes consistently support the potential role of a healthy diet in preventing dementia.

Based on this background, the Mediterranean–Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) diet has recently been proposed as a dietary pattern specifically created to prevent cognitive decline in older adults [

9]. The MIND diet is a hybrid of the Mediterranean diet and DASH diets, which emphasizes on the consumption of foods that improve brain health. The MIND diet score comprises 15 components, namely, 10 brain-healthy food groups (e.g., green leafy vegetables, nuts, legumes, whole grains, fish, poultry, and olive oil) and 5 food groups to be limited (e.g., red meat, butter, cheese, sweets, and fried foods). By analyzing data from the longitudinal Memory and Aging Project (MAP) cohort in Chicago, Morris et al. [

9] were the first to report that the MIND diet was significantly associated with cognitive changes. Among 960 participants followed for an average of 4.7 years, higher adherence to the MIND diet was found to be associated with significantly slower deterioration in global cognition and 5 cognitive domains. Notably, participants who achieved the highest diet scores exhibited cognitive aging profiles comparable with those approximately 7.5 years younger who had the lowest scores (β = 0.0106, p < 0.0001).

Although several studies have reported beneficial effects of the MIND diet on cognitive decline, inconsistencies persist because of variations in dietary composition, assessment tools, and participant characteristics across studies. For example, a 3-year clinical trial involving 604 cognitively normal but obese adults aged ≥ 65 years revealed that despite the effectiveness of the MIND diet combined with calorie restriction for weight loss, it did not significantly prevent cognitive decline [

10]. In another RCT of 41 middle-aged adults (40–55 years old), a 12-week MIND diet intervention combined with behavioral support (based on the capability, opportunity, motivation, and behavior model) improved mood and quality of life; however, no significant changes in cognitive function were observed [

11]. Differences in participants’ age, health status, intervention duration, and implementation strategies hamper the interpretation of findings and highlight the need for a comprehensive review of the cognitive benefits of the MIND diet.

Therefore, this study aimed to systematically review the existing literature to clarify the effect of the MIND diet on the cognitive function of older adults. The findings may serve as foundational evidence for the development of dietary guidelines tailored to the cognitive health needs of older Korean adults.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [

12] and followed a predefined protocol for identifying and selecting relevant studies. All PRISMA recommendations were applied, except for the quality assessment of the included studies.

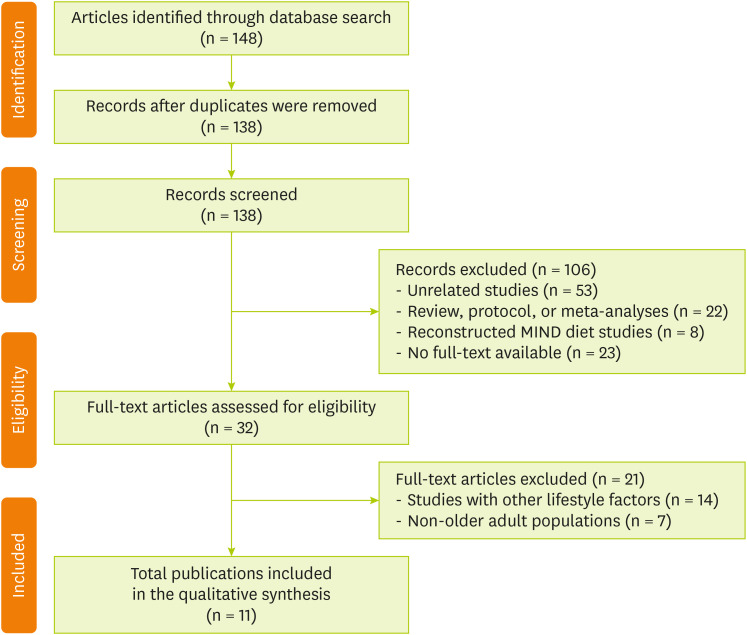

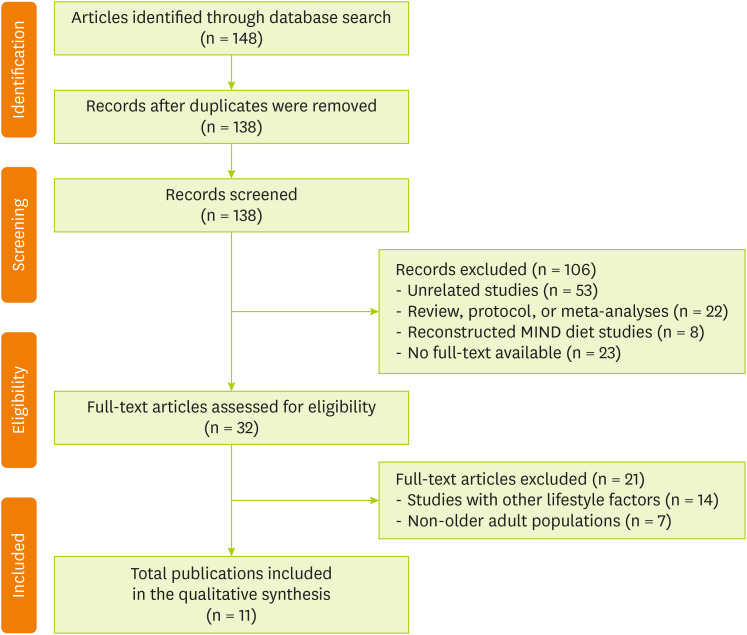

Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of article selection. A literature search was conducted in PubMed and Cochrane Library to extract articles published between 2015 and 2024 and reflect recent research trends by including studies from the previous decade. The search was conducted without language restrictions, and the primary search terms included “MIND diet,” “cognitive function,” and “older adults.” The database searches initially identified a total of 148 articles. After removing 10 duplicates, the titles and abstracts of the remaining 138 records were screened. During this phase, 106 articles were excluded for being unrelated studies (n = 53); review articles, protocols, or meta-analyses (n = 22); using reconstructed MIND diet scores (n = 8); and having no full text available (n = 23). Subsequently, 32 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Of these articles, 21 were excluded, namely, 14 that focused on lifestyle factors other than diet (e.g., physical activity and education) and 7 that included non-older adult populations (e.g., young adults). Finally, 11 studies met all the inclusion criteria, which were subsequently included in the qualitative synthesis. The search strategies applied to each database are detailed in

Tables 1 and

2.

Figure 1 Flow chart of the study selection.

Table 1 PICO framework

Table 1

|

Criteria |

Determinants |

|

Population |

Older adults aged ≥ 65 years who have consumed or are currently on the MIND diet |

|

Intervention |

MIND diet (a combination of the Mediterranean and DASH diets) |

|

Comparison |

Older adults who do not follow the MIND diet or a general dietary pattern |

|

Outcome |

Main outcome: effect of the MIND diet on cognitive function improvement |

|

Secondary outcomes: prevention of cognitive decline, reduction in Alzheimer’s disease risk, and improvement in memory and attention |

Table 2 Search strategies by database

Table 2

|

Database |

Search strategies |

|

PubMed |

#1 (Mediterranean-DASH diet intervention for neurodegenerative delay[Title/Abstract]) OR (MIND diet[Title/Abstract]) |

|

#2 (Alzheimer's disease[Title/Abstract]) OR (memory[Title/Abstract]) OR (learning[Title/Abstract]) OR (dementia[Title/Abstract]) OR (cognition[Title/Abstract]) OR (cognitive[Title/Abstract]) |

|

#3 (Aged[MeSH Terms]) OR (older adults[Title/Abstract]) OR (elderly[Title/Abstract]) OR (Older Persons[Title/Abstract]) OR (Old Age[Title/Abstract]) |

|

#1 AND #2 AND #3 |

|

Cochrane Library |

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Aged] explode all trees |

|

#2 (elderly):ti,ab,kw OR ("older adults"):ti,ab,kw OR ("elderly"):ti,ab,kw OR ("older persons"):ti,ab,kw OR ("old age"):ti,ab,kw |

|

#3 #1 OR #2 |

|

#4 (MIND diet):ti,ab,kw OR (Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay):ti,ab,kw |

|

#5 MeSH descriptor: [Cognition] explode all trees |

|

#6 (Alzheimer's disease):ti,ab,kw OR (memory):ti,ab,kw OR (learning):ti,ab,kw OR (dementia):ti,ab,kw OR (cognition):ti,ab,kw OR (cognitive):ti,ab,kw |

|

#7 #5 OR #6 |

|

#8 #3 AND #4 AND #7 |

The following information was extracted from the included studies using a predefined form: first author, publication year, country, sample size, mean age, participant characteristics, study design, duration, cognitive function measures, intervention, and key findings.

A single reviewer (S.K.) extracted the data. Although duplicate independent extraction was not performed, the extracted data were repeatedly checked for accuracy and carefully reviewed against the original articles to identify and correct any omissions or errors and minimize potential bias.

RESULTS

Description of the included studies

Table 3 summarizes the key characteristics of the 11 studies included in the review [

9,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. These studies were conducted in different countries, including the United States, Germany, Italy, and Switzerland, and most included predominantly White individuals (> 75%). These studies included 7 cohort studies, 2 cross-sectional studies, 1 RCT, and 1 case-control study. Regarding study duration, 7 studies exceeded 3 years, 2 lasted ≤ 3 years, and the 2 cross-sectional studies were categorized separately. The number of participants varied across studies, ranging from 106 to 5,143, totaling 17,201 individuals enrolled in the 11 selected studies. All studies were conducted among adults aged ≥ 57 years. Dietary adherence was assessed in all studies using the MIND diet score (0–15) based on the food frequency questionnaires, whereas cognitive function was evaluated using various standardized assessment tools. Most studies indicate that the MIND diet preserves the cognitive function of older adults, whereas some have shown associations with improved cognitive resilience (CR) and the prevention of early-onset dementia (EOD). In contrast, two studies did not report any significant effects.

Table 3Characteristics of the included studies

Table 3

|

First author (publication year) |

Country |

Sample size |

Mean age (yr) |

Participant characteristics |

Study design |

Duration |

Cognitive measures |

Intervention |

Key findings |

|

Morris et al. [9] (2015) |

USA |

960 |

81.4 ± 7.2 |

Older adults from the Rush project, 75% female, 95% White |

Cohort study |

4.7 years |

Annual structured assessments of 19 tests covering five domains (episodic memory, semantic memory, working memory, visuospatial ability, and perceptual speed), and global cognition |

MIND score based on Harvard FFQ; cognitive decline rate analysis |

Higher MIND adherence significantly slowed cognitive decline (β = 0.0092, p < 0.0001). Top tertile maintained cognitive level approximately 7.5 years younger. MIND outperformed MedDiet and DASH in predictive value. |

|

Cherian et al. [13] (2019) |

USA |

106 |

82.8 ± 7.1 |

Older adults with stroke history, mean 14.4 years of education, 16% APOE-e4, 72.6% female |

Cohort study |

5.9 years |

Five cognitive domains + global Z-score |

MIND score based on FFQ (tertile), association with cognitive trajectories |

Higher MIND adherence was associated with slower cognitive decline (β = 0.08; 95% CI, 0.01–0.16; p = 0.034). Semantic memory and processing speed also declined more slowly (p = 0.04). |

|

McEvoy et al. [14] (2017) |

USA |

5,907 |

67.8 ± 10.8 |

Community-dwelling adults ≥ 50 years, 59% female, 77% White, 14.5% Black, and 8.5% other |

Cross-sectional study |

Baseline data (cross-sectional analysis) |

Global cognition (0–27 points), memory, attention, and working memory |

MIND and MedDiet adherence (FFQ-based) |

Higher adherence to MIND and MedDiet was associated with better cognitive performance. The top tertile showed 35% lower risk of cognitive impairment (OR, 0.65; CI, 0.52–0.81; p < 0.001). |

|

Wesselman et al. [15] (2020) |

Germany |

389 |

69 ± 6 |

DELCODE study participants with subjective cognitive decline, MCI, family history of c, or cognitively normal controls; no dementia, 51.9% female |

Cross-sectional study |

Baseline data (cross-sectional analysis) |

CERAD battery assessing memory, language, executive function, working memory, and visuospatial ability |

MIND (0–15) and MedDiet (0–9) scores from the148-item FFQ; PCA-based dietary patterns |

Higher MIND and MedDiet scores were associated with better memory (MIND: p = 0.029). Language improved in the non-MCI group (p = 0.027). PCA pattern (“alcoholic beverages” and “grains and nuts”) positively associated with memory, language, and working memory. |

|

Agarwal et al. [16] (2019) |

USA |

809 |

80.7 ± 7.2 |

Older adults from the Rush MAP, no baseline disability, 74% female |

Cohort study |

5.3 years |

ADL, IADL, and mobility limitations (self-reported; not direct cognitive scales) |

MIND, MedDiet, and DASH scores based on the Harvard FFQ; tertile-based Cox regression |

Higher MIND adherence was associated with reduced risk of ADL disability (mid-tertile HR, 0.75; top HR, 0.67, p-trend = 0.001). IADL and mobility limitations also decreased (p-trend = 0.04, 0.02). MedDiet and DASH scores were significant for ADL and mobility in the top tertile only. |

|

Seago et al. [17] (2024) |

USA |

5,143 |

≥65 |

Participants without dementia, AD, or stroke in the Health and Retirement Study; 60% female, ~75% White, 15% Black, 10% other |

Cohort study |

6 years |

Global cognition composite (immediate/delayed recall, backward counting) |

Standardized MIND, MedDiet, and DASH scores from 2013–14 FFQ |

All three diets positively associated with baseline cognition. MedDiet (β = 0.03, p = 0.002) and DASH (β = 0.04, p = 0.004) slowed cognitive decline. MIND did not show significant association with cognitive decline (β = 0.02, p = 0.094). |

|

Dhana et al. [18] (2021) |

USA |

569 |

Mean age at death: 91 |

Older adults in Chicago with or without dementia, pre-mortem cognitive data and autopsy, 70.5% female |

Cohort study |

1997 death (diet assessed in 2004) |

Global cognition before death (Z-score), AD pathology, and other neuropathologies |

Cumulative MIND score based on 15 FFQ food groups |

Higher MIND score was associated with better cognition at death (β = 0.119, SE = 0.040, p = 0.003); significant even after adjusting for AD pathology (β = 0.111, p = 0.003). Not associated with non-AD pathology. |

|

Wagner et al. [19] (2023) |

USA |

578 |

84.1 (diet), 91.4 (at death) |

Older adults in the Rush project without dementia; repeated cognitive, diet, autopsy data; 72% female, 98% non-Hispanic White |

Cohort study |

Mean of 9 years (max of 23) |

Annual global cognition score based on 17 neuropsychological tests |

MIND diet score (0–15) based on the baseline FFQ |

Top tertile MIND adherence associated with higher CR level (MD = 0.34; 95% CI, 0.14–0.55) and slower CR slope decline (MD = 0.27; 95% CI, 0.05–0.48). Fish and legumes ↑ CR; butter/margarine, red meat, fried food ↓ CR. |

|

Cognitive resilience measures: CR level (higher-than-expected cognition), CR slope (slower-than-expected decline), both adjusted for nine postmortem neuropathologies |

|

Filippini et al. [20] (2020) |

Italy |

108 |

Onset age 59.8, survey age ~65 |

54 EOD patients and 54 caregivers, 57% female |

Case-control study |

4 years |

N/A (risk analysis) |

Dietary pattern analysis based on EPIC-FFQ (MIND, MedDiet, and DASH); food group intake |

Higher MIND adherence was linearly associated with lower risk of EOD. Excess intake of grains (> 350 g) and dairy (> 400 g) increased the risk. Whole grains, preserved fish, leafy greens, and nuts showed U-shaped or inverse associations. |

|

Barnes et al. [21] (2023) |

USA |

604 |

≥ 65 (range: 65–84) |

Cognitively normal, family history of dementia, BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, low MIND adherence (≤ 8), highly educated, 87.4% White, 65.2% female |

Randomized controlled trial |

3 years |

Composite cognitive Z-score, four cognitive domains, and MRI imaging |

MIND diet +250 kcal restriction vs. control diet (same kcal restriction and nutrition education) |

No significant difference in cognitive change at 3 years (MIND +0.205 vs. control +0.170 Z, p = 0.23). No difference in MRI measures. |

|

Sager et al. [22] (2024) |

Multi-national (Switzerland, Germany, France, Austria, and Portugal) |

2,028 |

74.88 |

Age ≥ 70, MoCA ≥ 24, no major illness in the past 5 years, 60.5% female |

Cohort study |

2.99 years |

MCI defined as MoCA < 26 and < 24 |

15-point MIND score based on the 216-item FFQ; analyzed cognition and inflammation markers (hsCRP and IL-6) |

No significant association between MIND adherence and MCI or cognitive decline at 3 years (MoCA < 26: OR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.94–1.04 and MoCA < 24: OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.96–1.10). |

Cognitive function maintenance and improvement

In total, 6 studies have reported that higher MIND diet scores were associated with better overall cognitive function in older adults. Specifically, long-term cohort studies have demonstrated that greater adherence to the MIND diet significantly slowed the rate of global cognitive decline. Morris et al. [

9] conducted a 4.7-year follow-up study involving 960 older adults (mean age, 81.4 years). They found that participants with the highest tertile of MIND diet scores experienced a 0.0106-unit slower annual decline in cognitive function than those with the lowest tertile (p < 0.0001), corresponding to an approximate cognitive age difference of 7.5 years. Moreover, significant protective effects were observed across all cognitive subdomains, including episodic memory (β = 0.0090, p = 0.001), semantic memory (β = 0.0113, p < 0.0001), perceptual speed (β = 0.0097, p < 0.0001), and working memory (β = 0.0060, p = 0.01). Similarly, Cherian et al. [

13] conducted a 5.9-year follow-up study involving 106 older adults with a history of stroke and reported that participants with higher MIND diet scores experienced a significantly slower rate of global cognition decline (β = 0.08, p = 0.034), with noticeable effects on semantic memory (β = 0.07, p = 0.043) and perceptual speed (β = 0.07, p = 0.059).

Positive associations were also observed between the MIND diet and cognitive function across cross-sectional studies. McEvoy et al. [

14] found that among 5,907 older adults in the United States, higher scores on the MIND diet were significantly associated with higher global cognitive function scores. The group with the highest scores had a mean cognitive score 0.8 points higher than the group with the lowest score (p < 0.001), and each 1 standard deviation increase in the MIND score was associated with a 14% reduction in the risk of cognitive impairment (odds ratio [OR], 0.70; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.56–0.86; p = 0.001). This finding demonstrates a linear relationship between MIND diet adherence and cognitive performance. Similarly, Wesselman et al. [

15] found that higher MIND diet scores were significantly associated with better memory (β = 0.045, p = 0.029) and language function (β = 0.027, p < 0.05) among 389 older German adults, and these findings remained consistent even after excluding participants with mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

Beneficial effects related to functional abilities in older adults were also observed. In a 5.3-year cohort study of 809 participants, Agarwal et al. [

16] reported that those with higher MIND diet scores had a 33% lower risk of being unable to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) and more than a 30% lower risk of mobility disability. Moreover, a significant inverse association was also observed with instrumental ADL disability risk, proposing that the MIND diet contributes to both cognitive health and prevention of functional disability in daily life.

Conversely, in a 6-year longitudinal study of a nationally representative sample of 5,143 US older adults, Seago et al. [

17] found that MIND diet scores were significantly associated with baseline cognitive function (β = 0.22) but not with the rate of longitudinal cognitive decline (β = 0.02, p = 0.094). Thus, the MIND diet may have varied long-term protective effect on the characteristics of the study population and observation period, with a potential role in improving the initial cognitive status.

Overall, higher adherence to the MIND diet was found to be associated with better cognitive function and a slower decline rate across multiple domains, with additional benefits for functional abilities.

Enhancement of CR

Two studies reported that adherence to the MIND diet was associated with enhanced CR, which was defined as the ability to maintain cognitive function despite having brain pathology, such as AD. In a cohort study, Dhana et al. [

18] analyzed data from 569 participants with available MIND diet scores, cognitive function assessments, and autopsy results at the time of death. They examined the association of the MIND diet scores with cognitive performance near death. Even after adjusting for AD and other neuropathological indices, higher MIND diet scores showed a significant association with better cognitive function (β = 0.111, standard error = 0.037, p = 0.003), indicating that the MIND diet contributes to cognitive preservation independent of cumulative pathological burden. Similarly, Wagner et al. [

19] analyzed data from 578 older adults who underwent cognitive assessments over an average follow-up duration of 9 years before death. They found that participants with the highest tertile of MIND diet scores had a 0.34-unit higher CR level, representing better-than-expected cognitive performance relative to neuropathological burden (95% CI, 0.14–0.55; p = 0.001). Moreover, the CR slope, indicating a slower rate of cognitive decline over time, was 0.27 units more favorable in the highest tertile group than in the lowest tertile group (p = 0.01). Food group-specific analyses revealed that higher intake of vegetables, fish, and legumes demonstrated positive associations with CR indicators, whereas greater consumption of saturated fat-rich foods such as butter, margarine, and red meat exhibited a negative association.

The results revealed that adherence to the MIND diet enhanced CR; thus, individuals maintained better cognitive performance beyond neuropathological burden, underscoring its potential role in preserving cognitive health in aging.

Reduction of EOD risk

Filippini et al. [

20] conducted a case–control study involving 54 patients with EOD and 54 matched controls in Northern Italy. They reported a protective effect of the MIND diet on EOD. Participants with the highest tertile of the MIND diet scores had a 69% lower risk of developing EOD than those with the lowest tertile (OR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.11–0.90). This protective association was stronger and more linear than that observed for the DASH diet (OR, 0.60) or the Mediterranean diet (OR, 0.45). Thus, the MIND diet may serve as an effective dietary strategy for EOD prevention.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review comprehensively analyzed the effects of the MIND diet on the cognitive function of older adults. Among the 11 included studies, 9 reported positive relationships between higher MIND diet scores and the preservation or improvement of cognitive function, enhanced CR, and a reduced risk of EOD in older adults.

Compared with the Mediterranean diet and DASH, the MIND diet emphasizes the consumption of berries and green leafy vegetables. Flavonoid-rich berries, particularly anthocyanidins, are well known for their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, which are beneficial for cognitive function. A longitudinal study indicated that participants who consumed more berries, such as blueberries and strawberries, had significantly slower cognitive decline rates [

23]. A recent large cross-sectional study found that older adults who consumed more dark-green vegetables had significantly higher cognitive scores, particularly strong positive associations with immediate and delayed memory abilities [

24]. Collectively, the MIND diet may offer cognitive benefits to older adults by highlighting food groups known to support brain health.

Compared with other dietary patterns, the MIND diet was also reported to have stronger protective effects on cognitive decline. Morris et al. [

9] analyzed the MAP cohort and revealed that the standardized regression coefficient for the MIND diet was higher than that for the Mediterranean and DASH diets. Previous studies have suggested that the MIND diet positively affect brain health through various physiological pathways. In a cross-sectional study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, higher MIND diet scores were significantly associated with lower levels of triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, total cholesterol, fasting blood glucose, and HbA1c, as well as reduced disease activity [

25]. Accordingly, the MIND diet may improve cerebrovascular health by enhancing metabolic health and modulating inflammation, ultimately protecting cognitive function. Furthermore, based on postmortem analyses of brain tissues, Agarwal et al. [

26] reported that individuals with higher MIND diet scores had significantly lower levels of β-amyloid deposition and global AD pathology. Notably, the group with higher intake of green leafy vegetables exhibited the lowest levels of AD pathology. Thus, the MIND diet may help prevent cognitive decline by inhibiting the accumulation of β-amyloid and tau protein, which are key pathological markers of AD.

Nevertheless, not all studies have demonstrated significant benefits of the MIND diet. No clear effects were uncovered in studies with intervention periods of < 3 years. For example, in a RCT involving older adults with obesity but with normal cognitive function, cognitive function improved in both the intervention and control groups (mild caloric restriction). However, changes in white-matter hyperintensities, hippocampal volumes, and total gray and white matter volumes on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were comparable between the two groups [

21]. Similarly, the DO-HEALTH prospective cohort study conducted across 5 European countries reported that adherence to the MIND diet was not associated with incident MCI or changes in inflammatory markers over 3 years [

22]. Compared with the results of studies reporting positive findings, the two studies had relatively short follow-up periods (≤ 3 years), which may have contributed to the discrepancies in the outcomes.

Several limitations should be noted regarding the studies included in the review. First, the difference in study design and cognitive measurements render it challenging to synthesize the results. Various study designs were employed, such as cohort studies, randomized controlled trials, cross-sectional studies, and case–control studies. Cognitive measurements also varied across studies, including MRI, physical function assessments, Montreal Cognitive Assessment, and global cognition scores, making it impossible to perform a meta-analysis. Second, data were extracted by a single reviewer (S.K.). Although duplicate independent extraction was not conducted, the extracted data were repeatedly checked for accuracy and were carefully reviewed against the original articles to identify and correct any omissions or errors and minimize potential bias. Third, the study participants lack racial diversity. Most studies were conducted with White as the primary population. Although this review excluded studies based on reconstructed MIND diet models during literature selection, studies that have adapted the MIND diet for Asian populations suggest that cognitive protective effects can also be expected among Asians. Huang et al. [

27] developed a culturally modified MIND (cMIND) diet that reflects traditional dietary patterns for older Chinese adults. In their large-scale analysis of 11,245 participants, higher cMIND diet scores were significantly associated with a lower risk of cognitive decline and impairment in ADLs. Similarly, the MY-MINDD diet score was developed in Malaysia, and a study involving 810 older adults showed that the highest tertile group had a significantly lower risk of MCI than the lowest tertile group [

28]. Therefore, future studies should involve systematic reviews and large-scale RCTs focusing on Asian populations.

CONCLUSION

This systematic review revealed that the MIND diet may positively affect the maintenance and improvement of cognitive function, enhance CR, and prevent EOD in older adults. These effects were prominent in long-term cohort studies, and the protective effects of specific food groups, such as berries and green leafy vegetables, and the associations with physiological mechanisms, such as the inhibition of β-amyloid and tau protein accumulation, were also reported. However, results must be cautiously interpreted owing to the diversity in research designs and cognitive assessment tools e employed, differences in intervention periods, and racial limitations of the study participants. Thus, further systematic reviews and large-scale RCTs focusing on Asian populations are warranted.

NOTES

-

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

-

Author Contributions:

Conceptualization:Lee S.

Data curation:Kim S.

Formal analysis:Kim S.

Investigation:Kim S.

Methodology:Lee S, Jang EH.

Project administration:Kim S.

Resources:Kim S.

Supervision:Lee S.

Validation:Lee S, Jang EH, Kim S.

Visualization:Kim S.

Writing - original draft:Kim S.

Writing - review & editing:Lee S, Jang EH.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chen S, Cao Z, Nandi A, Counts N, Jiao L, et al. The global macroeconomic burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: estimates and projections for 152 countries or territories. Lancet Glob Health 2024;12:e1534-e1543.

- 2. World Health Organization. Ageing and health. 2024. cited 2025 June 25. Available from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health

- 3. Statistics Korea. 2024 Statistics on the elderly. 2024. cited 2025 June 25. Available from https://www.kostat.go.kr/board.es?act=view&bid=10820&list_no=432917&mid=a10301010000

- 4. National Institute of Dementia. National Institute of Dementia annual report 2024. 2025. cited 2025 June 26. Available from https://www.nid.or.kr/info/dataroom_view.aspx?bid=310

- 5. Swaminathan A, Jicha GA. Nutrition and prevention of Alzheimer’s dementia. Front Aging Neurosci 2014;6:282.

- 6. Nurk E, Drevon CA, Refsum H, Solvoll K, Vollset SE, et al. Cognitive performance among the elderly and dietary fish intake: the Hordaland Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;86:1470-1478.

- 7. Okubo H, Inagaki H, Gondo Y, Kamide K, Ikebe K, et al. Association between dietary patterns and cognitive function among 70-year-old Japanese elderly: a cross-sectional analysis of the SONIC study. Nutr J 2017;16:56.

- 8. Kean RJ, Lamport DJ, Dodd GF, Freeman JE, Williams CM, et al. Chronic consumption of flavanone-rich orange juice is associated with cognitive benefits: an 8-wk, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in healthy older adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;101:506-514.

- 9. Morris MC, Tangney CC, Wang Y, Sacks FM, Barnes LL, et al. MIND diet slows cognitive decline with aging. Alzheimers Dement 2015;11:1015-1022.

- 10. Harris E. MIND diet no better than control for adults at risk of dementia. JAMA 2023;330:585.

- 11. Timlin D, McCormack JM, Kerr M, Keaver L, Simpson EEA. The MIND diet, cognitive function, and well-being among healthy adults at midlife: a randomised feasibility trial. BMC Nutr 2025;11:59.

- 12. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000100.

- 13. Cherian L, Wang Y, Fakuda K, Leurgans S, Aggarwal N, et al. Mediterranean-Dash Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) diet slows cognitive decline after stroke. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2019;6:267-273.

- 14. McEvoy CT, Guyer H, Langa KM, Yaffe K. Neuroprotective diets are associated with better cognitive function: the health and retirement study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65:1857-1862.

- 15. Wesselman LMP, van Lent DM, Schröder A, van de Rest O, Peters O, et al. Dietary patterns are related to cognitive functioning in elderly enriched with individuals at increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Nutr 2021;60:849-860.

- 16. Agarwal P, Wang Y, Buchman AS, Bennett DA, Morris MC. Dietary patterns and self-reported incident disability in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2019;74:1331-1337.

- 17. Seago ER, Davy BM, Davy KP, Katz B. Neuroprotective dietary patterns and longitudinal changes in cognitive function in older adults. J Acad Nutr Diet 2025;125:785-795.e9.

- 18. Dhana K, James BD, Agarwal P, Aggarwal NT, Cherian LJ, et al. MIND diet, common brain pathologies, and cognition in community-dwelling older adults. J Alzheimers Dis 2021;83:683-692.

- 19. Wagner M, Agarwal P, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA, Schneider JA, et al. The association of MIND diet with cognitive resilience to neuropathologies. Alzheimers Dement 2023;19:3644-3653.

- 20. Filippini T, Adani G, Malavolti M, Garuti C, Cilloni S, et al. Dietary habits and risk of early-onset dementia in an Italian case-control study. Nutrients 2020;12:3682.

- 21. Barnes LL, Dhana K, Liu X, Carey VJ, Ventrelle J, et al. Trial of the MIND diet for prevention of cognitive decline in older persons. N Engl J Med 2023;389:602-611.

- 22. Sager R, Gaengler S, Willett WC, Orav EJ, Mattle M, et al. Adherence to the MIND diet and the odds of mild cognitive impairment in generally healthy older adults: the 3-year DO-HEALTH study. J Nutr Health Aging 2024;28:100034.

- 23. Devore EE, Kang JH, Breteler MM, Grodstein F. Dietary intakes of berries and flavonoids in relation to cognitive decline. Ann Neurol 2012;72:135-143.

- 24. Liu Y, Liu W, Yang Y, Liu H, Liu J, et al. The association between dietary dark green vegetable intake and cognitive function in US older adults. Nutr Bull 2025;50:69-81.

- 25. Safaei M, Kheirouri S, Alizadeh M, Pirovi AH. Association between Mediterranean-Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay diet and biomarkers of oxidative stress, metabolic factors, disease severity, and odds of disease in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Food Sci Nutr 2024;12:3973-3981.

- 26. Agarwal P, Barnes LL, Dhana K, Liu X, Zhang Y, et al. Association of MIND diet with cognitive decline among Black and White older adults. Alzheimers Dement 2024;20:8461-8469.

- 27. Huang X, Aihemaitijiang S, Ye C, Halimulati M, Wang R, et al. Development of the cMIND Diet and its association with cognitive impairment in older Chinese people. J Nutr Health Aging 2022;26:760-770.

- 28. M Zapawi MM, You YX, Shahar S, Shahril MR, Malek Rivan NF, et al. Development of Malaysian-MIND diet scores for prediction of mild cognitive impairment among older adults in Malaysia. BMC Geriatr 2024;24:387.